Filmmaker Kirsten Tan and actress Oon Shu An in conversation

The first Objectifs Film Club session, held online via Zoom, featured filmmaker Kirsten Tan and actress Oon Shu An in conversation on Kirsten’s little known early short film Come (rent it here).

The first instalment of our recap of their discussion focused on Kirsten’s experiences in the making of one of her earliest short films, Come (2007), a sex comedy set in South Korea, and her journey and philosophy as a filmmaker. Read it here.

In this second and final instalment, we recap their discussion of Come in relation to Shu An’s role in sex comedy Rubbers (2014) and their responses to questions from audience members. The conversation has been slightly paraphrased for brevity. Please note that the films referenced as well as the discussion touch on mature themes.

Kirsten: Shu An, Rubbers is a series of interconnecting stories about people’s sex lives and their use of condoms, and the style is pure comedy, highly ridiculous and absurd — let me know if that’s a terrible summary!

Shu An: It sounds right! It’s really quirky and out there and a bit whoa, what’s happening?

Kirsten: You played Momoko — a Japanese porn star, a fantasy character — who pops into this character’s life…I guess he’s maybe a fan? In the film this fan is in a situation where he had a condom stuck on his penis, and Momoko is extremely helpful and tries to execute this thing called “oral technique” as mentioned in the film, with hopes of removing the condom…

Shu An: And then I get stuck. We wander around Singapore with me stuck on.

Kirsten: I really enjoyed your performance. You went all out and committed to a role where you spend most of your time on another actor’s nether regions. What was your first reaction when you read the script? Did you have any hesitation, and what made you decide to do the film?

Shu An: The director and producer were too shy to send me the script. They suggested meeting up; I had worked with both of them [before]. When I was talking to them about it I could feel their discomfort. I initially had huge reservations because…it’s about image, isn’t it? But because I knew the director as a person and a filmmaker I kind of knew he wasn’t going to super-sexualise it. I knew where he was coming from and I knew it wouldn’t be gross. I didn’t think it would become exploitative. So I decided, let’s just do it. I do quite enjoy his sense of humour. It’s super out there.

Kirsten: What was your reaction upon viewing the finished film?

Shu An: This is hard for me because in general, I don’t like watching myself. So I generally cringe each time I do. It took me a long time to tell my parents I was going to take this role, and then I told them not to watch the film. It was very difficult. Just how do you have that conversation?

Kirsten: Apart from knowing the director’s work, was there anything else that drew you to the role?

Shu An: I thought it would be quite fun.

Kirsten: Did you prepare a lot for the role? When they finally had the courage to give you the script, did you regret taking on the role? And how in general did you prepare for it?

Shu An: They talked to me about the role and passed me the script at the same time. I didn’t agree to it before reading the script. I had to go watch quite a bit of porn!

Kirsten: So what were your insights?

Shu An: Different countries have slightly different styles, the kind of genres they like, the sounds they make. The dynamic between the man and the woman kinda changes in different countries.

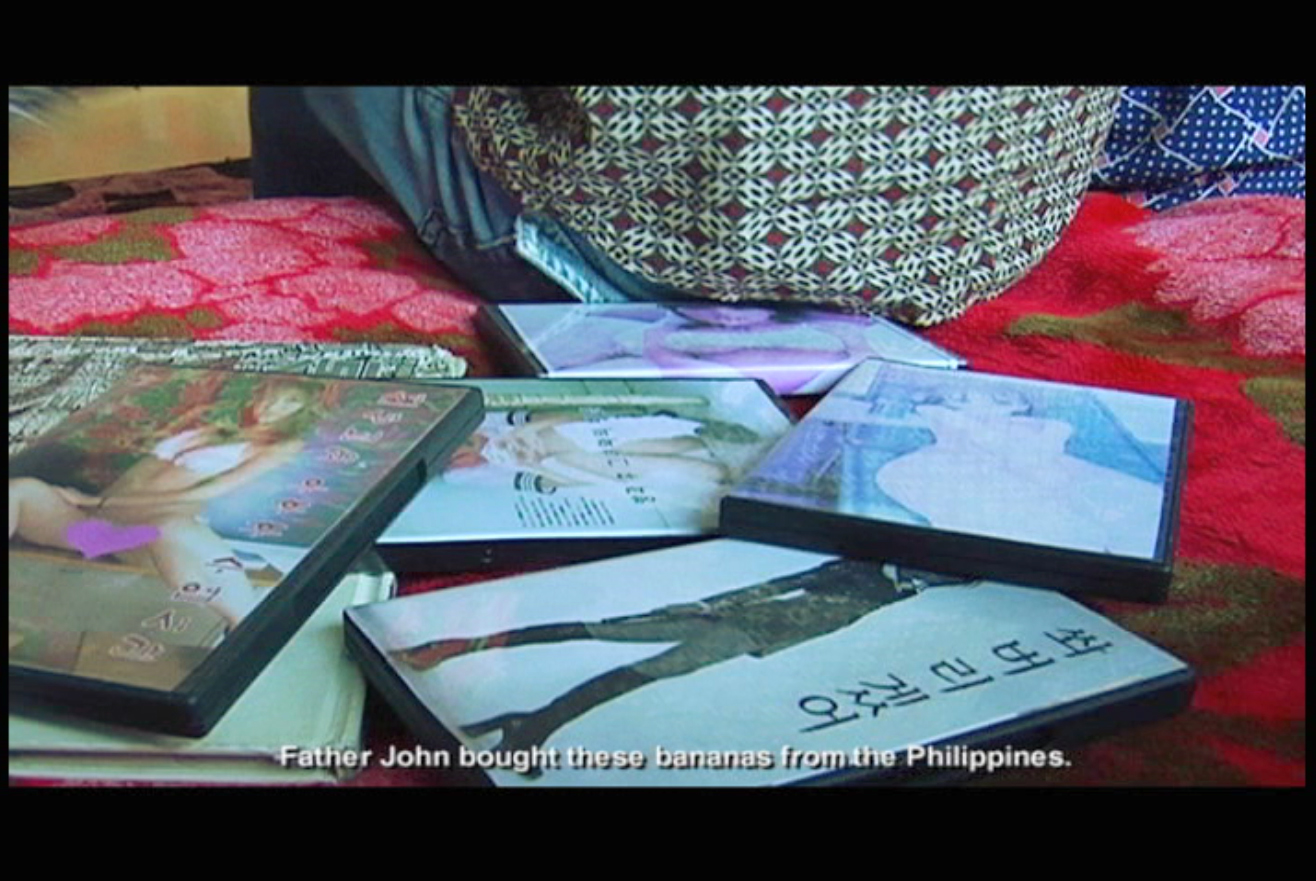

Kirsten: For Come I did a lot of porn research also, because I had to find the appropriate level for the young boy to watch, and the right level that wouldn’t turn off my audience. I felt like the softcore animation [we eventually went with] was just the right entry level for the boy.

From “Come” by Kirsten Tan

Shu An: Did you have to speak to his mum about this?

Kirsten: There was an intense discussion between the producer and the boy’s mum. The mum agreed to the role after she read the script. She suggested maybe we shouldn’t share the script with her son, and I asked, how am I going to direct him? So she decided to just generally tell him the storyline. He was quite excited because it was his first time acting in a film but when it came to the masturbation scene, I wasn’t even sure how much he knew about sex in the first place and I definitely didn’t want to be the person who first gives him sex education. I consulted his mum and she said maybe we don’t have to tell him everything so I told him that he’s just shaking a cup the whole time. And he was really just doing that the whole time.

Shu An: And then when his dad comes in, what was the reaction?

Kirsten: I told him “you’re not supposed to shake a cup and your dad caught you shaking a cup”.

Shu An: Do you think he knew, though?

Kirsten: I think so because he was already 11? In the context of everything else happening I feel like he definitely knew? But it was just full of euphemisms in the way I had to direct this.

From “Come” by Kirsten Tan

Audience Member: What was the significance of the kimchi in the film? Could you also speak about music choices and how Jesus Christ Superstar was chosen as the pivotal song?

Kirsten: I function on a very lateral, associative level. Kimchi, for me, in its spicy, gooey stickiness feels inherently sexually foul. I thought it was just funny for the father to reach for the kimchi and really enjoy it. I feel like if I were to write that scene today it would probably be cut, or my producer would tell me it’s excessive. But at that point I had the freedom to do whatever I wanted so, I just left it there.

I hope this isn’t too disappointing but I can’t remember why I chose Jesus Christ Superstar. It was probably that the song had an irreverence, and tongue in cheekiness to it that I felt tonally fit the film.

Audience Member: What is the difference in the way women in Singapore and in Korea think about sex and related experiences both back when Come was made in 2007 and now?

Shu An: Singapore is still quite conservative about sex in many ways. Many families don’t really seem to talk about it. When I was watching Come I thought “oh, this was years ago” but I can totally see a family now still kind of freaking out about it in the same way.

Women’s movements over the past few years have also changed the way that we see a woman’s sexuality. I remember being very shamed or shame-y about sexuality in general while growing up. But now almost nobody bats an eyelid.I feel like there has been a shift in some sense, but also not in a lot of ways.

Kirsten: It’s a bit nebulous because it’s very hard to consider all women as a whole monolith. Though we are both women, we are so different. But I guess just on a very general level — I talked about Korean society being this overflowing cup trying to put a lid on itself. For Singaporeans, the cup is not even full. For Koreans there is unbridled passion that needs to be controlled while for Singaporeans, the flow is not there from the get-go. A lot to unpack why we’re like that. I’m commenting on society and culture generally, not even just the women.

[Note: While the session came to an official close soon after this point, many attendees stayed on for further conversation with Kirsten and Shu An in which many interesting questions were raised. We have included a selection and the speakers’ responses here.]

Shu An: How did your studying Literature at NUS lead to filmmaking?

Kirsten: I did some film studies modules at NUS and we were introduced to films like Citizen Kane and Battleship Potemkin but I felt that was not a great way for people to be introduced to films. They are great classical works but at the same time it was hard not to snooze. I partly enjoyed it but I also feel like

when it comes to learning film, there is so much one can do beyond the classroom. Most of my film education was in libraries on my own, or through attending events like this, screenings, listening to filmmakers talk, listening to DVD extras and so on.

Having a sound understanding of stories — even if it’s classical literature, poetry — is helpful in understanding the structure of storytelling. I feel like most of my grounding as a filmmaker comes from literature in a way. Polish filmmaker Pawel Powlikowski once said to me “film is second-rate literature” and it stuck because that’s kind of brutal but also kind of true. In literature, you can go much deeper than films. But I shouldn’t be so ungenerous to compare forms like that.

Shu An: The skill of condensing all of one’s thoughts into an hour and a half, or 60 minutes, or a few minutes though, that’s also very difficult to do.

Kirsten: It’s also very difficult but I feel like you have to be extremely intelligent as a writer, there is no getting away from that, but as a filmmaker you can get away a little and afford to be a little more dense…

Shu An: I disagree! I feel like the type of engagement is different. For people who find it very difficult to read, for example, no matter how deep the writer goes, if the ideas don’t connect with somebody else, then what’s the use of thinking so deeply? Same for those super arty films, if they don’t connect with people. It’s a different form of intelligence to be able to transmit information to somebody else.

Kirsten: Maybe we have to be more specific and break down what intelligence means? Assuming that intelligence means clarity of thought, eloquence, being able to break down difficult concepts into something simple and being able to extrapolate from it. I feel like in film in a way you don’t need such crystal clarity sometimes and can function more in terms of dream logic, which is in itself a kind of intelligence.

Audience Member: Instinct is so often overlooked as a form of intelligence. I have a question for Kirsten and Shu An that could help us unpack intelligence and instinct and how the two correlate or not. In the sex scene between the parents in Come I was very curious about the realism of the middle aged characters’ sex — what struck me was the way the woman patted her husband’s shoulder.

From “Come” by Kirsten Tan

Shu An: Yes! I was like whoa, that is real!

Audience Member: I was really struck by that and I want to know whether that was something you told the woman to do or whether she did it on her own.

Kirsten: That moment was actually in the script. That’s just observation. Often I create by thinking “what if?”. I was thinking a middle aged couple probably even if they still have a good sex life, it’s probably not that new and exciting, probably a bit perfunctory.

Audience Member: That is a kind of high form of intelligence! It’s not something you can do a test on. There are a lot of different types of intelligence that don’t get talked about enough as well. For example there is a kopitiam aunty who makes the best Milo ever. I just can’t make Milo like that but it’s a real skill that’s specific to her.

Kirsten: Maybe I was just not generous enough in defining what intelligence means.

Shu An: It’s also in our conditioning that there’s certain types of intelligence that are more important. To be able to make a good cup of Milo does require a lot of intelligence and you need to remember how everyone likes their Milo — that’s a kind of love also and a huge amount of emotional intelligence which we don’t give enough credit to.

So much work like cleaning the house, taking care of meals is all traditionally female duties that are now even more important and are still unpaid. So much of that isn’t compensated because we don’t peg a value to it. It’s taken for granted. But imagine if everyone just stopped cleaning and cooking? We’ve been brought up in a world where “intelligence” is classified in certain ways. That’s why I reacted so strongly to what you said in terms of comparing literature and film.

Kirsten: I agree that I was thinking of “intelligence” in its most typical form.

Audience Member: Shu An, in Rubbers it seemed to me that you and [actress] Yeo Yann Yann were the only ones who had control over their roles, even if the filming environment was empowering and the director was open. The both of you went in with a very specific take on your respective characters and I felt that you were leaning into the element of camp. That made sense to me because a porn star is like a vision, a fantastical beast in a way. Was this pure instinct or a developed thing you wanted to put into this character? I know you as a person and I remember you sounding several octaves higher in the film, for example. Was that stuff you thought about beforehand and prepared for, or did it come naturally to you as you were doing these scenes?

Shu An: It was like half and half. From all the porn that I watched, I saw that Japanese porn is generally very high pitched, the way women speak is very subservient. I kind of took that and when I got to the set I got a sense of the energy there and went with it.

Audience Member: Kirsten, how would you describe your progression as a filmmaker both in thematic choices as well as style?

Audience Member: I really liked Come and I felt the work you did before that was a lot more interested in form. Could you speak to that more, and how did your notions of narrative filmmaking change from there?

Kirsten: I’m just a pretty short-term thinker, which is good and bad.

In terms of the progression of my shorts a lot of it is a reaction to the current moment I am living in and a reaction also to my previous work. Because every time you do something there are regrets or things you want to work on, and the next film is a chance to do that.

I would actually be a bit mortified if people saw Come alone and thought that was all I was capable of as a filmmaker. There is always a risk when you put out new work. That is the risk of it “becoming” you, or that the particular work will be something you are categorised or remembered by even if that’s just something you’re trying out. So viewing a body of work is more interesting for me when I’m tracking a writer or an artist or a filmmaker.

In terms of my progression I wouldn’t say it’s extremely planned but when I look back into the past there are certain themes that always emerge. I am interested in multi-character stories, in time as a theme, in all my films there is always a light kind of surreal, absurd element and sometimes it’s more obvious than other times. At the same time when I am writing I never realise it, it’s not planned, it’s not like I am going to write this film about x. In hindsight you look back and understand yourself with it. Having been through film schools and all that the most fascinating thing for me is always witnessing that for my classmates, certain patterns emerge too. i

I’d say that even if you’re not a creator you have a theme. You have certain obsessions that will revisit you constantly. And if you’re a filmmaker, that’s the stuff that you write about and make over and over again.

Audience Member: And that’s from a creator’s point of view. From a performer’s point of view, Shu An, aside from work you’ve written yourself, you are more beholden to roles that other people write for you. Do you see things or patterns coming up that are pertinent to you? What do you do with your own obsessions, are you able to place them in your work?

Shu An: When I was younger this was not so clear to me because when you’re in acting school you pick your own monologues for exercises and you resonate with the pieces [you choose]. But when you go into acting in other people’s stories you are there in service of their script. That’s something I’ve been learning to navigate over time. You can share your input with the filmmaker but at the end of the day, it’s their story.

With topics I feel very strongly about, like ethics or the way a woman is represented, as I get more educated about those issues, the more I bring it up. If I really disagree with the way something is phrased or framed even after bringing it up, I consider how much of it is within my professional right to disagree and how much of it is my professional duty to just do the role. I try to be clear about that before I take on the project — I will maybe have a chat about it, if they’re open to talk about it. But if we totally don’t see eye to eye, I’ve realised it’s better for my mental health to just not do it.

Kirsten: Do you feel like it’s something you’re only able to do now? I’m curious if performers and actors especially in Singapore feel a lack of agency because roles are so limited, it’s almost tough to turn down a role. But you’re at a level where you can comfortably do it. Did you have to work your way into this? How do you navigate this lack of control in the things you’re putting out into the world? In a way it’s also pretty unfair because a film is the director’s work, but you’re the face of it.

Shu An: An incident from when I was younger left a huge impact on me. A student filmmaker asked me to be part of his film and the character was pitched to me as so much fun, a great character. Eventually I found out I had to be in lingerie — the character was just there bouncing on a bed with another woman in lingerie and a man. I felt like I had been sold a very different representation of what this character is. I’m sure she was fun and had a backstory but nobody would see it, all they would see onscreen is two girls bouncing on the bed in lingerie. I had already committed to the role and felt it would not be nice if I left. I wanted to be responsible but at the same time I don’t think the role was explained to me responsibly. Since then I’ve started becoming more aware of this. Personality-wise, I also just tend to say something if I don’t agree with it. It has worked both for and against me. I think what’s nice is that now I can have the conversation, whereas previously I just had to say yes or no.

Kirsten: These are very important conversations. We were never taught ethics in film school but it’s so important. A director / actor relationship can be messed up in so many ways: control, mind games…

Shu An: There are practices I hear of that are just not okay, like directors telling an actor to slap a fellow actor but not warning them in advance.

Kirsten: Sometimes I do that too. I feel I have to contextualise this by saying there really has to be an environment of trust.

Shu An: But there are also people who will use that logic and abuse it.

Kirsten: I feel so much for performers. In a production you are the frontline. It is such a vulnerable position. I don’t think a lot of people actually understand what that’s like. Everyone is watching you but you are expected to be emotionally naked the whole time.

Shu An: The business of being human in general…it’s very difficult for us to be vulnerable in human everyday life. When you’re on shoot the whole day, forever roll / cut / roll / cut, you have to get into it and then snap out of it, and then go back in and cry or whatever.

Kirsten: It’s just not psychologically healthy! Actors really need therapy, man.

Shu An: But then in general I think therapy gives everyone the tools to process your emotions and speak them. That’s the other part of growing as an actor — learning how to find your own boundaries within other people’s boundaries, trying to see where they’re coming from. But I don’t envy the position of a director either. There are so many things to steer and then at the same time you’re trying to tell a story.

Kirsten: I think with Pop Aye the most difficult thing was to hold the concept and all the nuance and tone in my head while being on set with a crazy big elephant. The internal and external were really jarring. You are trying so hard to preserve the core of the film while having to handle the logistics. You need a lot of focus. Sometimes I feel barely human when I am directing.

Shu An: It does require a superhuman focus. You also need to look after your actors and translate to them what you want from them and that’s so hard.

Audience Member: Kirsten, is there any reason why foreign countries like Thailand in Pop Aye and Korea in Come feature so much in your process? Or foreignness as in Dahdi which is about a Rohingyan refugee. Do you feel pressure to create films set in Singapore?

Kirsten: This is an excellent question but it’s more of a chicken and egg question. I’ve been away for more than a decade and left Singapore at a pretty early age. Though I am still quite Singaporean — as you can tell with my accent and everything — it was really tough for me to be in Singapore because my parents really hated that I am a filmmaker. For the longest time, I wasn’t even out to them. They would not have accepted it. It was just much easier for my headspace to exist outside of the country. So a lot of the “foreignness” wasn’t really a choice but just because I was shooting where I was, which was not Singapore.

The more I was outside of the country the more I felt for outsiders. Even in Singapore I’ve always felt like an outsider. My whole life I’m just rooting for underdogs. Inevitably, all my films have a more empathetic lens towards people who are not within the centre. I’ll always have empathy for the freaks, the weirdos and the ones who don’t belong.

Come, along with with other short films by Southeast Asian filmmakers, is available to rent on the Objectifs Film Library. More titles will be able to view at Objectifs’ premises (after we reopen, depending on the Covid-19 situation).