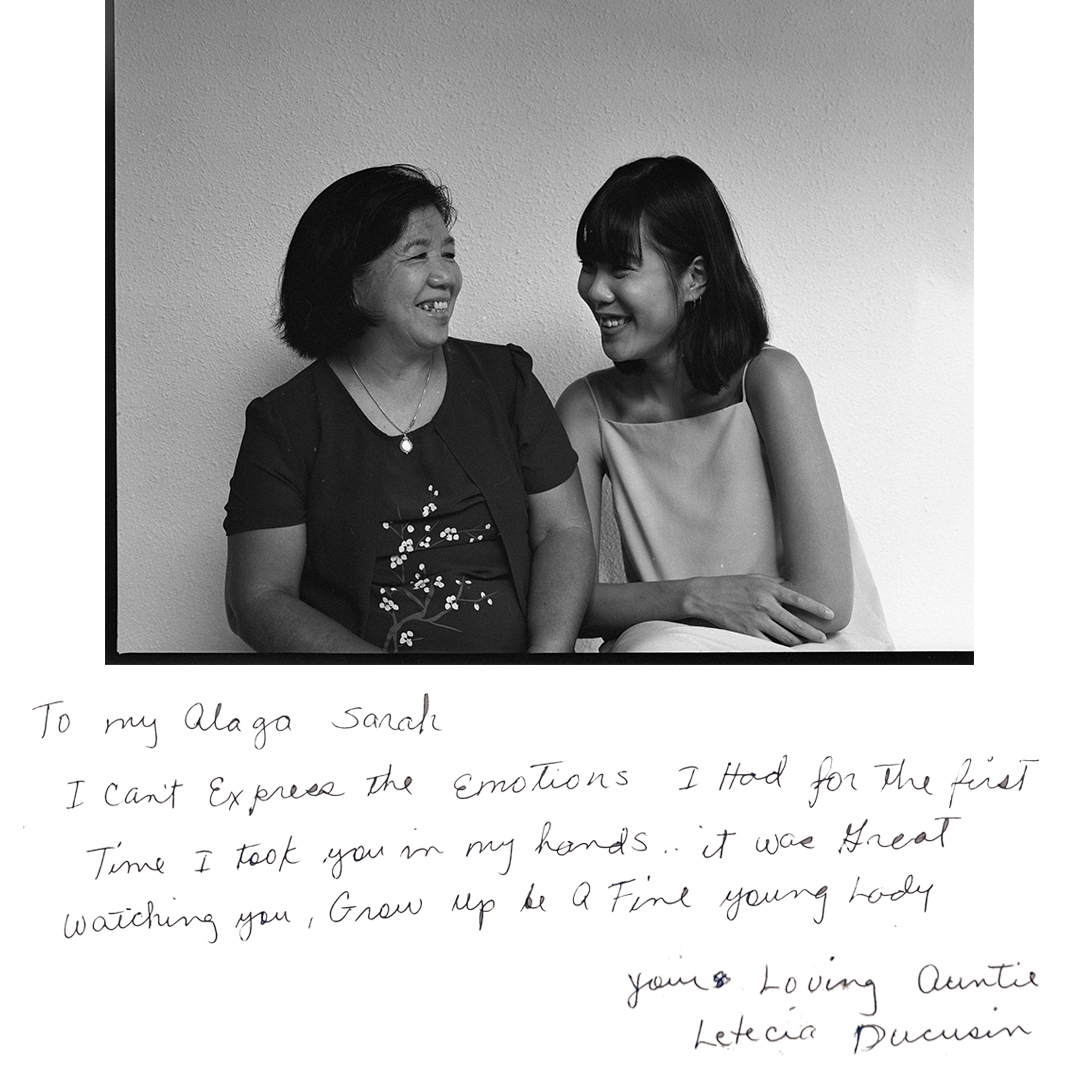

Documentary Award Recap with Emerging Category recipient Sarah Isabelle Tan and mentor Veejay Villafranca

Read a recap of the online artist talk for Alaga, an exhibition by Sarah Isabelle Tan, the recipient of the Objectifs Documentary Award 2020 (Emerging Category).

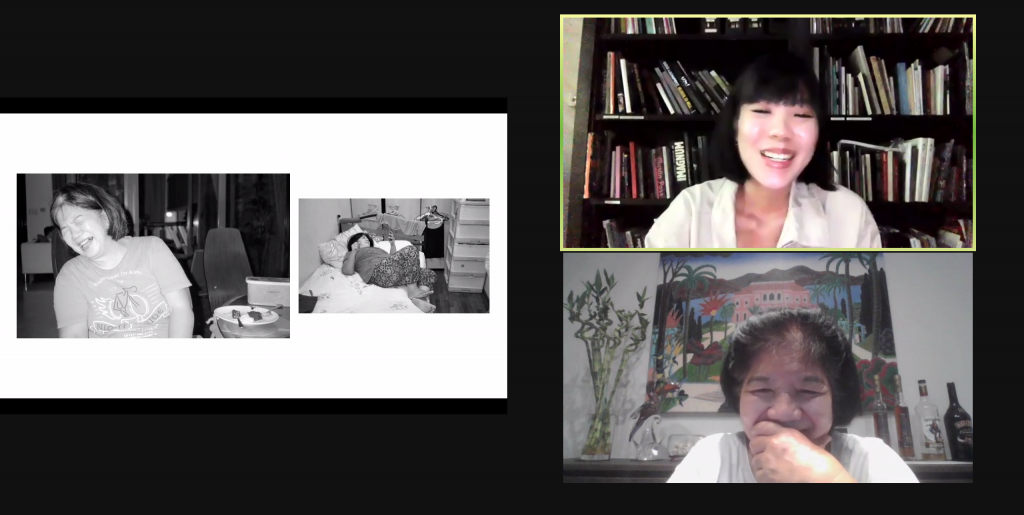

The session is a dialogue between artist Sarah Isabelle Tan and her mentor Veejay Villafranca on the process of working on the project, moderated by the Programme Director of Objectifs, Chelsea Chua. Letecia B. Ducusin, a foreign domestic worker from the Philippines who is employed by Sarah’s family and is the subject of Alaga, was also present. The discussion has been paraphrased for brevity.

[Clockwise, from top left] Sarah Isabelle Tan, Letecia B. Ducusin, Chelsea Chua and Veejay Villafranca

Chelsea: Sarah’s approach to photography has always been more conceptual while Veejay has such a strong background in photojournalism. What was it like working together as a mentee and mentor, and how have these differences informed your experience?

Veejay: It was a year-long process of unravelling and putting together what Sarah wanted to say. The starting point was that Sarah was starting to get heartbroken that a woman who stayed with her for almost three decades would be leaving. How could she use her memories and experiences to form Alaga?

Sarah: I decided to embark on Alaga when Aunty Leti received her retirement notice from the Ministry of Manpower. The impending separation was a loss I had to anticipate. Where had the years we spent together gone? When someone is always around in your everyday life, you never truly question what they mean to you. In my childhood I never fully grasped the person Aunty Leti was to me.

Veejay: Why did you decide to pick up a camera in response?

Sarah: I know that time cannot be grasped, but wanted to try to document the nuances and moments that define our relationship, and express myself, through photography.

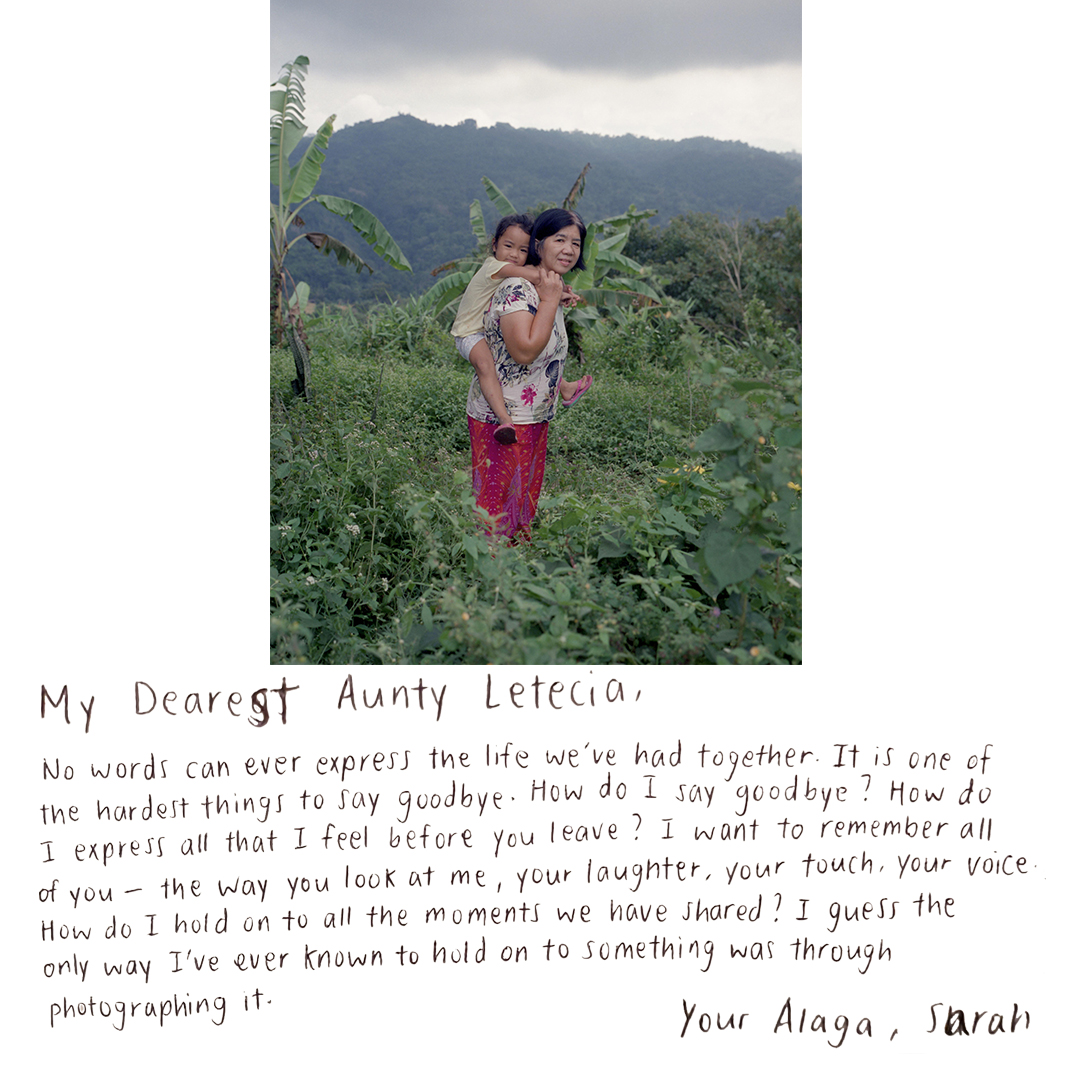

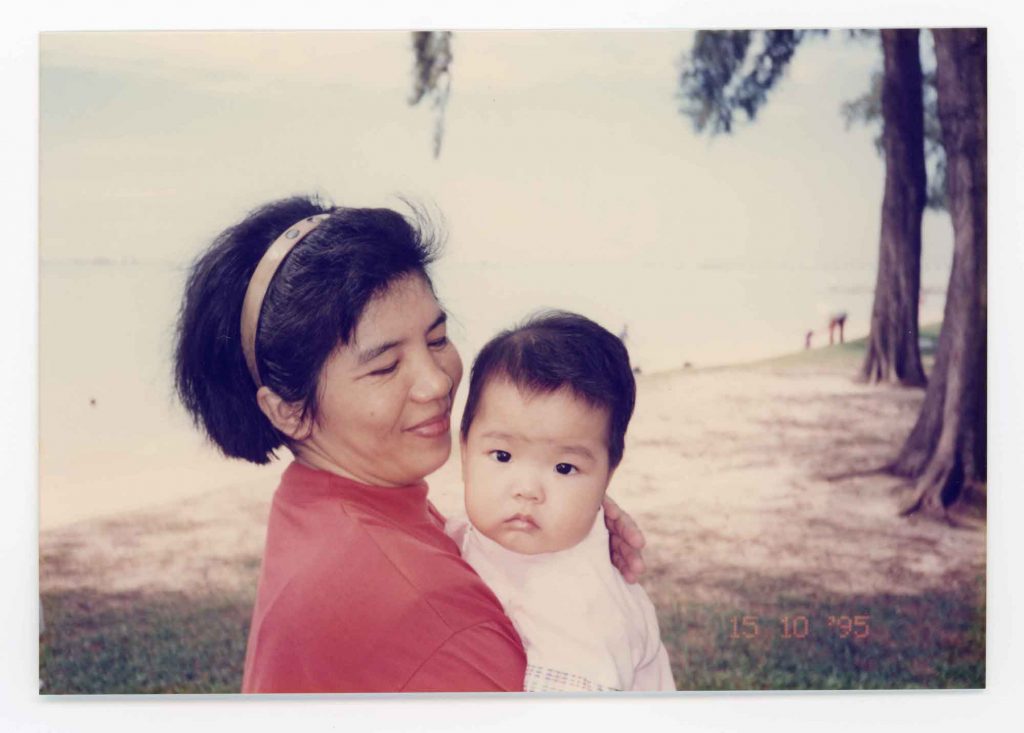

I visited Aunty Leti’s hometown in the Philippines in December 2019 and made photographs while also hearing stories recounted by her and her family, exploring the landscapes they grew up and live in, and looking together at their old family photos. Looking at the parts of Aunty’s life I wasn’t a part of, opened up new dimensions to the project which included revisiting my own family archives and reflecting on my own memories. I don’t actually remember being in some of my childhood photos with Aunty, though they feel familiar.

The rest of the photographs were made in Singapore last year, mainly within the spaces of the home, alongside audio recordings and texts by Aunty Leti and myself. I captured ordinary moments like Aunty drinking her morning coffee — gestures which I will miss when she leaves Singapore.

Chelsea: You had presented a small selection of these photos in a group show.

Sarah: Yes, that was still in the early stages of the work. I was still exploring how best to show the relationship between Aunty and myself. The project was more personal and showed the relationship and time that had passed.

Audience Member: What did you learn about yourself when making these photographs? Were there other images that showed Aunty Leti’s subjectivity towards you as her alaga?

Audience Member: Was there a time in the making of the project when Leticia became the documentarian herself?

Sarah: In the early stages we explored how the idea of the gaze worked both ways. I began work on Alaga by considering what I mean to Aunty Leti and by contemplating myself as the subject of not only Aunty Leti’s care but also her gaze. In the early stages I would photograph her and also have her photograph me — with her phone, the device that she is comfortable with. I wanted to see how she really views me. When we love someone and give them a space in our lives, the relationship itself gives us a certain identity. I realised that when Aunty Leti leaves Singapore for good, no one will ever call me alaga again.

We discussed quite a bit how I’d insert myself within this narrative. I was really looking at Aunty Leti, not just in the everyday way you see somebody but through sitting and listening, and through conversations. Aunty is from an indigenous group called the Igorot and I learned from her about their culture and practices.

From “Alaga” by Sarah Isabelle Tan

In the final edit exhibited, there are many photos of Aunty and hardly any of myself. Through my discussions with Chelsea and Veejay I realised that the photographs I had taken already showed the gestures of care that Aunty Leti has given me. I realised that for me, family is not just about blood relations but more about what feels like a safe space. With Aunty, it feels like that.

Chelsea: How did Veejay’s experiences living and working in the Philippines influence your understanding of the work and the kind of approaches you’ve suggested to Sarah?

Veejay: Before Sarah formed the main idea about alaga meaning “being taken care of”, we had many discussions about the experiences of Filipinos working overseas. I shared some information and other bodies of work about women, mothers and Filipina women to help her into the next phase. I also shared with her my personal experiences of meeting, interviewing and spending time with overseas Filipino workers. I think most Filipinos would also know at least one overseas contract worker and have heard their stories.

Most of the time overseas foreign workers, Filipino workers, are in the news for what happens to them, the abuses they experience. Sarah’s approach is a bit unorthodox from a journalistic perspective because she’s starting from herself. It’s very refreshing and another way of telling the stories of other people and discussing bigger issues of migration, economics and so on.

With Sarah’s intention I saw a great opportunity to tell a more nuanced sort of story or give a wider perspective on the experiences of overseas Filipino workers, especially Aunty’s generation who may be the first or second generation to work in this region. Some worked in the Middle East and some in Europe but the ones who stay in Asia have a different sort of experience. They’re near their home country but far from their families.

Sarah could not fly back to the Philippines to shoot due to the Covid-19 pandemic. So we considered what other aspects of Aunty’s life in her last few months in Singapore — now that she’s almost retired — we could still visualise: her packing balikbayan boxes, attending a birthday party, chatting with her son, her days off, her chilling in her room and using social media, watching videos on her phone.

In traditional documentary work, those scenes may not mean a lot because they are not “strong news images”. But in new forms of storytelling, these do matter, especially when the final output is an exhibition. I too learned a lot in the process about not only using what we see in front of the camera as documentarians, but also learning more about the subject, becoming more intimate, trying to be more intricate in determining metaphors.

Sarah: Veejay really encouraged me to push the meaning and concept of alaga by exploring the nurture and care that many foreign workers — mainly women — bring with them across geographical distances. There’s an outflow of labour and the sacrifices that come with it, like their families that they leave behind, how they manage to raise their kids while caring for strangers overseas. Veejay pushed me to examine how the immigration of women passes on the culture of caring for someone to a stranger.

Veejay: Aunty Leti, what did you feel when you saw the completed exhibition? What are your plans after you retire?

Letecia: (Translated from Tagalog by Veejay) I cannot believe that the person I took care of would grow up to be someone documenting my story. After I retire I’ll wait a year or two and maybe by then Sarah will have children for me to take care of!

Sarah: Ultimately, Alaga is a really personal body of work and something that I hold really close to my heart. It’s really fulfilling and heartwarming to see everything come together — all these years and all the life left yet — and become somewhat tangible. It’s something I can hold onto as a remembrance and celebration of a wonderful woman that has cared for me all my life.

Letecia with Sarah as an infant.

Audience Member: What advice would you give photographers looking to make work centered on personal and intimate themes? How can we manage the tension between conceptualisation and execution?

Sarah: Alaga is my first documentary work and this was one of the challenges I faced: How do I bring the intimacy of emotional moments into documentary work, which is largely objective? Veejay and I went back and forth on this. I also learnt a lot from Veejay’s methodology. I tend to get very wrapped up in my own head at times, thinking of 10 different ideas at once. Veejay helped keep me grounded by identifying two to three topics to go in-depth into.

Veejay: I kept pulling Sarah back to these two avenues: Aunty Leti’s life and Sarah’s life. How do you merge the two together? This type of work, documenting something personal, is a mixed bag. Of course, a lot of it is rooted in traditional documentary: you need a certain workflow, methodology and to observe, research and be very keen on your subject’s life. You need to be curious and committed.

If someone wants to pursue a personal project it’s very much valid to include a diaristic perspective. But also always keep in mind that others — from different demographics, who speak different languages — will see your work and consider how you can communicate with them, help them understand what you have to say and its nuances.

Stay tuned for Noise and Cloud and Us at Objectifs’ Chapel Gallery in late Jun 2021, by Shwe Wutt Hmon in collaboration with Kyi Kyi Thar, curated by Guo-Liang Tan. Shwe was the recipient of the Objectifs Documentary Award 2020 (Open Category).

Read about the recipients of the Objectifs Documentary Award 2021 here.