By Chananun Chotrungroj for the Objectifs Short Film Forum 2021

The Short Film Forum, part of the Objectifs Short Film Incubator 2021, saw film-makers and film-lovers from all over Southeast Asia tune in to a packed weekend of free online lectures and panel discussions by international industry experts.

Read on for a recap of director of photography and artist Chananun Chotrungroj’s lecture “Why is Creating a Visual Language Important?”, primarily using her work on The Third Wife by Ash Mayfair as a case study. This recap, in which the terms “cinematographer” and “DP” (director of photography) are used interchangeably, also incorporates Chananun’s responses to audience members’ questions.

Chananun Chotrungroj is a director of photography and artist based in Los Angeles whose works include the feature films Pop Aye by Kirsten Tan, The Third Wife by Ash Mayfair for which she was nominated for the 2020 Independent Spirit Award for Best Cinematography, and Materna by David Gutnik which won Best Cinematography at the Tribeca Film Festival 2020. While pursuing an MFA in Film at New York University, she was awarded the Ang Lee Fellowship and Department Fellowship and received the Nestor Almendros Award for Outstanding Cinematography by a Woman in 2013 and 2015.

Chananun Chotrungroj

Origin story

Chananun grew up in Thailand watching Bollywood films and movies from Hong Kong on her family’s projector and in cinemas. She always wanted to make movies but it felt impossible as it seemed that only the very rich could afford to do so, and it seemed an uncommon profession for women. She studied journalism in college as “[she] thought it was kind of related to visual storytelling” but also with a higher likelihood of securing employment.

After university, Chananun worked as a stills photographer on a film set where she met Niramon Ross, the first female DP in Thailand, who had more than a decade-long career in commercial television and whose first feature film credit was the famous horror movie Shutter.

Chananun shared: “After I met Niramon and loved my experience on the set, I knew I could do it too. I had actually never doubted my ability, but only whether I could make a living. After seeing Niramon do this job, it unlocked something in me. I just went for it and never questioned it. Because it was my dream since I was so young, I felt I could sacrifice anything to make it happen. I worked a lot on short films and then went to film school.”

Starting out as a DP was challenging because the projects Chananun was involved in barely had any budgets. She recalled: “It was about working smart with the resources we had. If I used all the time and resources to make a perfect image that doesn’t mean anything it’d be a waste; it could go to giving the actor more takes.”

“My role as DP is not to create beautiful shots and technically perfect lighting but to find what serves the story. I always talk to the director and ADs (assistant directors) to figure out what we have and what is important for the story.”

Chananun’s suggestion for those starting out as DPs is applicable more broadly to anyone aspiring to a career in the creative industries: “instead of waiting for projects, create them or make them happen, by supporting your friends”. The first short film she shot was Sink (watch it here) by Singaporean filmmaker Kirsten Tan, after they met in Korea and became friends.

Chananun recounted: “Kirsten shared her dream to make this film and I said I could help her make it happen. We ended up shooting it in Thailand. It’s hard at the start but it’s possible if you’re dedicated and support other filmmakers as well.

“It will never work if you wait for an already successful filmmaker to pick you. It’s about growing up together. Surround yourself with creative, talented people who don’t have to be successful in film already but you see their potential, their curiosity, and that they have stories to tell; and that they sync with you.”

First encounters with the script

As an experienced DP now, Chananun commits to projects if she reads and loves the script, and if she likes and trusts the director, though “that doesn’t mean that I listen to every single thing they say. I try not to impose my own visual style — that’s neither fair nor exciting — but work with them respectfully to try and support them visually.”

Because she started out shooting friends’ films, Chananun’s process with directors tends to be quite collaborative even up till now. In the US, when her agent sends her a script, the director may ask her to do a visual treatment after a conversation. She prepares this “not really coming from myself but coming from the notes I took about what the director wants”. Rather than a completed document, it is like a folder that they will collaboratively “pick from and add to”, until they are aligned in their vision.

Chananun starts by reading the script “just for entertainment”: “On my first read, I let myself just be a reader with no prejudices, and read how I’d read a novel, or manga…not even like I’m preparing to work.” She considers how the story leaves her feeling, what touches her.

Keeping these emotions in mind, from her second read, she begins to think through how the visual language can help convey these feelings, and starts a conversation with the director, during which she takes notes and asks many questions. “These are collaborations and I don’t want to assume it’s meant to be the way [I interpreted it]…it is about finding what is right for the film, which has to come from what the director has in mind.”

Pre-production from visual treatment to shot lists

After understanding the director’s intentions and aligning on “what is right for the film”, Chananun will create a visual treatment for the film which she elaborated on with reference to The Third Wife by Ash Mayfair. A visual treatment “allows [the team, including the director, cinematographer, costume designer and production designer] to be on the same page and help each other in building the visuals that support the story”.

Chananun first read the script for The Third Wife three years before the project raised sufficient budget — a timeline that is common for independent films. During this period, she and Ash would talk about the project occasionally, but when they were ready to make the film, they would discuss it daily for almost three months — though for not more an hour each time, as Chananun explained the risk of creative burnout if they delved into too much detail – discussing the visual treatment and shot list. In the second month, Chananun went to Vietnam to scout all the possible locations and came up with the visual treatment.

In preparing the visual treatment for The Third Wife, Chananun and Ash “talked a lot about how visual language could convey a lot of emotion without the characters talking”. Hence, they created moodboards for each character rather than just exterior and interior palettes. “We tried to treat it like each character has their own life and we try to find the language to say more about them.”

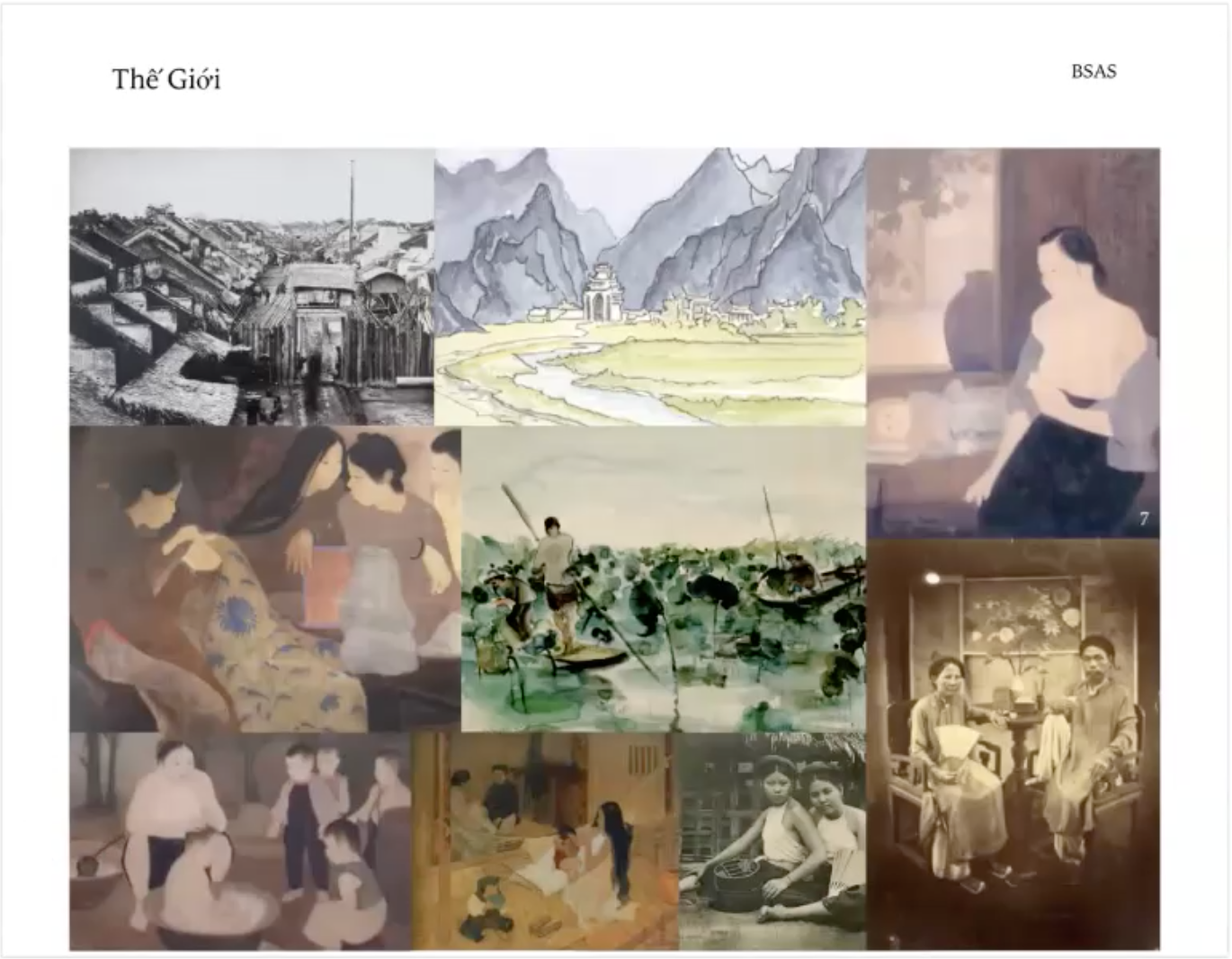

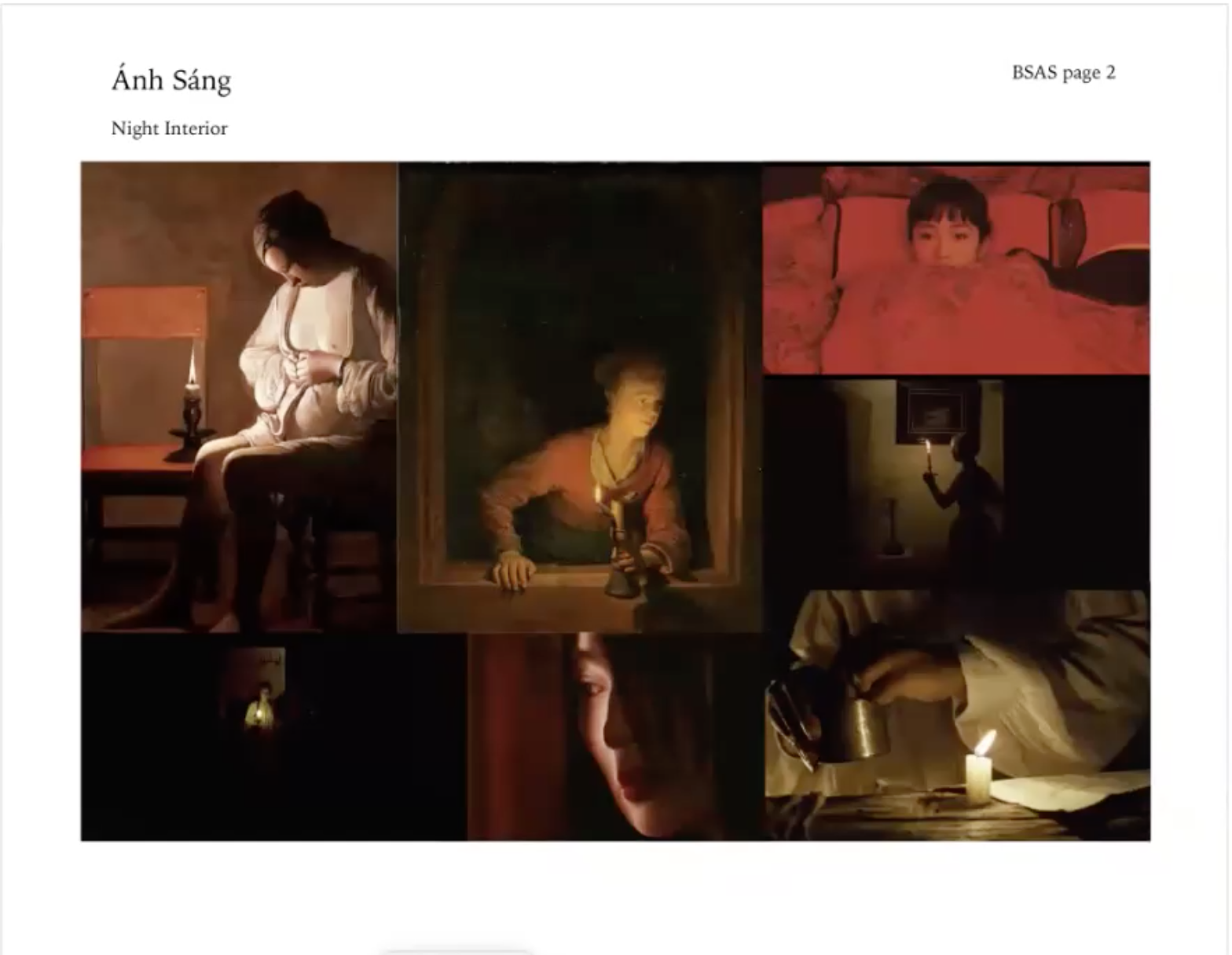

The moodboard for the world of the feature film “The Third Wife” by Ash Mayfair, set in 17th century Vietnam. (Credit: Chananun Chotrungroj)

Chananun starts with the world of the film. With an open mind, she gathers visual references whose textures convey the desired emotions and give a sense of “what is surrounding this story and the characters”. “Your whole life experience could be inspiration. It’s about what you have in your head and finding visual references to communicate it to other people. You need to keep fuelling the ‘stuff’ in your head.” While “the Internet has everything”, having grown up pre-Internet, she is also used to doing research offline, and especially recommends libraries and museums.

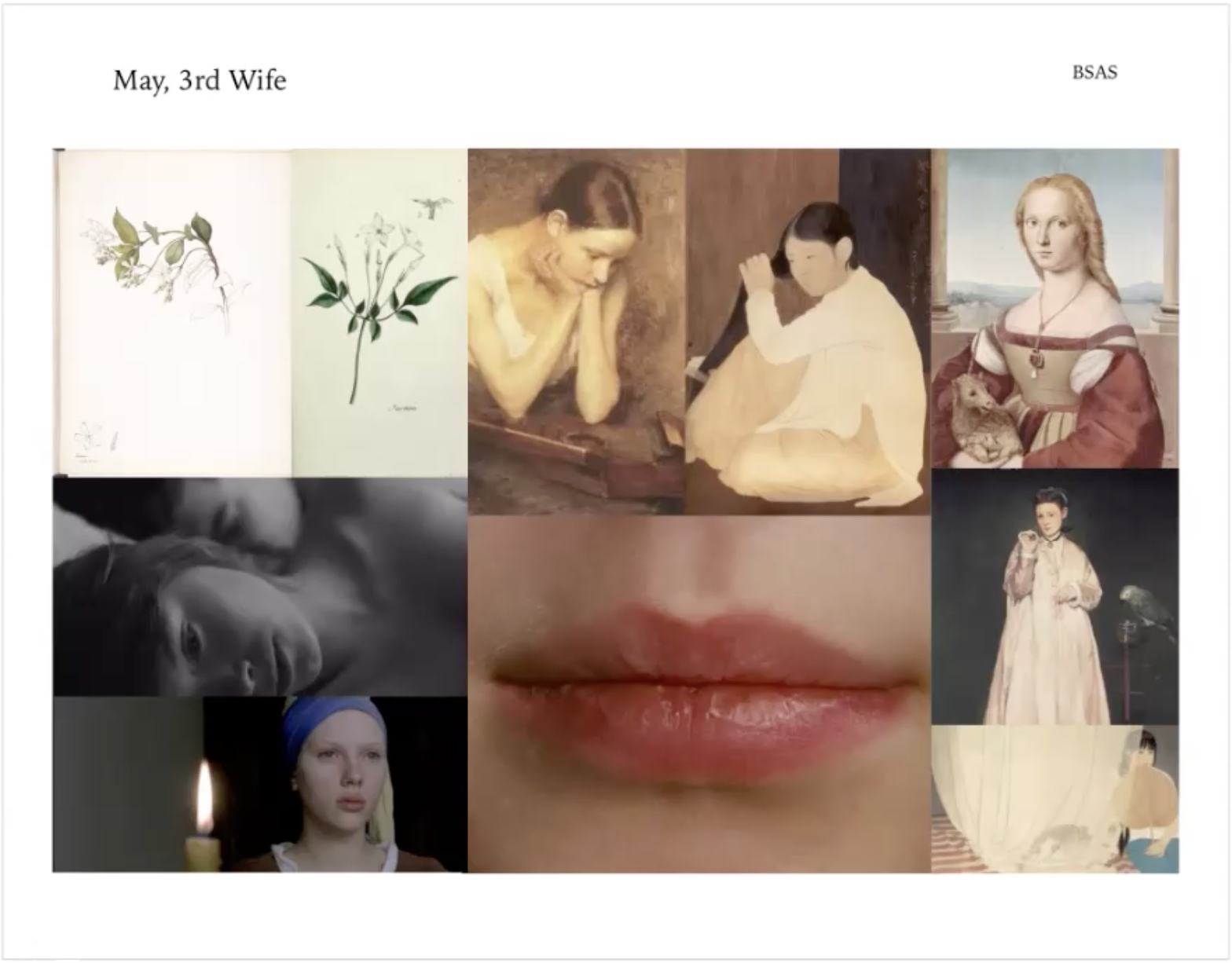

Next, she moves on to the main characters. InThe Third Wife, May is a teenage girl who has just married an older man and becomes the third wife of the household. Director Ash Mayfair wanted to convey May’s initial freshness and her slow loss of innocence. In addition to references that convey softness and the supple skin of youth, Chananun wanted to translate May’s nervousness onto “parts of her body, like her lips, skin or hands”.

Moodboard for the titular character of “The Third Wife” by Ash Mayfair – May is a young teenage girl who has just become the third wife of an older man. (Credit: Chananun Chotrungroj)

Beyond the literal, Chananun also included metaphorical imagery such as the mosquito net: in the film, the household is in the silk business, but in addition, the cocoon-like net also represented a young girl’s maturation into a woman, much like a caterpillar’s metamorphosis into a butterfly. She and Ash also spoke with the costume designer and production designer to “find a material that is not synthetic but really like silk or cotton so it would reflect light or let it through the way it used to be during the period the film is set”.

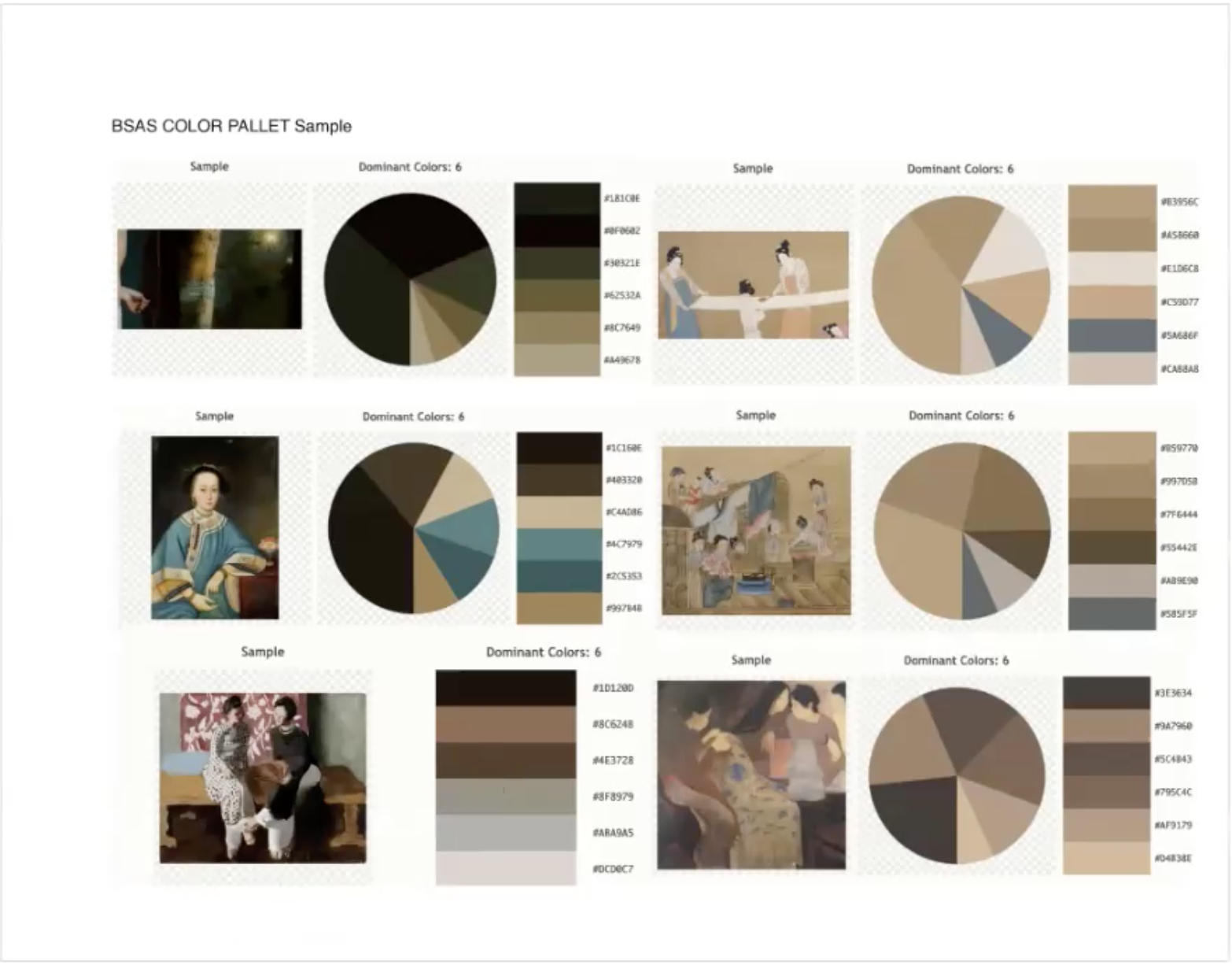

After collating the references for the main and then supporting characters, Chananun works on the colour palettes for the film, which she shares with the costume designer and production designer as well. “It’s essential we communicate clearly; when I set up the lights or am briefing the gaffer, I know for sure what material I’m working with for that costume for example”.

Colour palettes for “The Third Wife” by Ash Mayfair (Credit: Chananun Chotrungroj)

Lighting

Chananun “thinks of the movie as a whole first” and advises: “Find one way to deal with lighting, and then in each scene, think about the emotion, and what lighting feels natural and not too forced. Even though the scenes might be filmed in the same room, the lighting could differ. It’s a fine line between pushing too hard and getting it just right. I pay attention to what else is in the shot, the colours in the shot – do they go well with the emotion? ‘Go well’ doesn’t have to mean they have to complement each other; a stark difference could be meant to evoke discomfort.”

For The Third Wife the principle was that “all the light came from outside; there were no lights close to the actors like near their hair”. She decided not to place any lights in interior settings as she wanted to convey as authentically as possible the essence of 17th century Vietnam, where the film is set. Because it would have been so hot in the day and people spent most of their time working in the sun, houses would be kept darker to keep it cooler inside. “I feel it’s really wrong to put any lights close to the actor. I wanted a natural feeling but also had to work with the realities of a very dark location. We wanted the light to be like sun coming through windows, doors, and its position would change with time — it could go lower and lower.”

For the exterior day shots, the team wanted to capture the essence of the north of Vietnam, where it is cooler and there is a lot of fog in the morning, so they scheduled their shoot to get the wide shots early in the day.

The moodboard for night interior shots for “The Third Wife” by Ash Mayfair takes into account the socioeconomic context of 17th century Vietnam where gas and oil were expensive, and the materials with which and extent to which a person’s room was lit would be indicative of their status. (Credit: Chananun Chotrungroj)

They also worked with other departments. “Each wife in the film has her own small house which should feel different, reflecting their difference in status. For instance, May is the young new wife from a poor family who was married off because her father owed [May’s husband] money. So May’s room is very sparse, there’s not much in it. But the first wife Ha’s house is bigger and has many lanterns. We even discussed what the sources of lighting would be in their rooms — gas and oil was expensive at the time and if you were of higher status, your room may be lit with many lanterns and candles. This conveys without saying out loud the dynamics between the wives and differences in status.”

Shot Lists

There was no storyboarding done for The Third Wife. Chananun does shot lists and “draw[s] stick people on them for critical scenes” to illustrate what she and the director have in mind in order to work more efficiently when shooting. The extent of specificity for shot lists may vary from project to project depending on the director’s preference but for Chananun, she always asks questions and advises: “If you’re not clear, don’t let it go. When fighting for time and [to protect] your budget, it helps to know as much as you can and to be prepared and have no mistakes on set. I need to be very clear in the way that I create the world, for the director to feel comfortable on set.”

In response to an audience member’s question about how an iconic childbirth scene in The Third Wife was filmed, Chananun elaborated: “We had very little time with the babies so we had to pre-light everything right before they came on set. There were so many characters in the room and we blocked all of them in advance too. We also had boiling water around to create the steam that [director] Ash wanted as we could not use smoke machines in the presence of babies. That’s what made the scene feel very heavy and humid, in addition to excellent performances.”

The actress playing May researched what childbirth is like and the actresses playing the first and second wives have given birth in real life. All the women on set who have given birth shared their experiences during rehearsals. Chananun shared:

“I like to be on set during rehearsals. I don’t do anything. I just sit there and make friends. It helps make the actors, especially young actors and non-actors, feel more comfortable with the person closest to them when they perform, which is the camera operator.”

During rehearsals Chananun is also able to “understand the person’s moves; even though they are acting, they have their natural way of moving and talking that comes across [in the performance]”. As she does not know Vietnamese, for The Third Wife she had the script translated and memorised what the characters were talking about. She shared: “Not knowing the language actually worked better for me because if the visuals I’m looking at aren’t right, I can feel it. If I don’t understand what’s going on, it means something is wrong.”

Mise-en-Scene

Succinctly summarising the responsibilities of the DP as “everything you see in the picture”, Chananun shared that it is crucial for the DP and the director to communicate with other departments about mise-en-scene. Attention must be paid not just to what is in the foreground of a scene as every detail from background colours to extras’ costumes is crucial and deliberately chosen, constructed, included to guide viewers in how to feel.

Sometimes, they will go through an exercise of brainstorming “what more we can add to a shot that can additionally help to tell the story and emotion, than what we have already planned. We challenge each other to see who can come up with something that is still consistent with the visual bible we have”. For example, in the birth scene in The Third Wife, May is hoping to have a baby boy as in the world of the film a woman’s status would then be elevated and she would be more secure for her whole life. Ash and Chananun wanted the audience to feel the sense of anticipation that May’s future would be contingent on the outcome of that one night.

By having the other wives present to support May, as opposed to showing her giving birth alone with just a midwife, the audience would be guided to consider issues of guilt as Ha, another wife who had suffered a miscarriage previously, would be shown still selflessly helping May. Chananun said: “We see that a lot of the competition between the wives is not about them disliking each other but because their world is set up for them to challenge each other. So we had them appear together in this crucial moment for May which could go really well or really bad.”

Working on experimental films

The Edge of Daybreak by experimental filmmaker Taiki Sakpisit was a project Chananun worked on without knowing the director personally, but through colleagues. In her first meeting with him she confessed she “didn’t know what to do as it’s a really unusual film” and asked if he had considered shooting his own film”. But he insisted he wanted to work with her.

Chananun shared that it is very challenging to work with experimental filmmakers or those from a visual arts background compared to narrative filmmakers. She “worked hard to dig into Taiki’s head to get everything he could give me to help me understand. He talked very conceptually and was very particular about the lighting and blocking of certain shots. [She] really had to follow his direction.” Taiki emphasised it was more important for her to “feel” the scene and for them to be on the same page about the feeling.

Chananun and Taiki did not create a lookbook for The Edge of Daybreak but had a folder comprising Taiki’s prior research which conveyed how he wanted the movie to feel and look. She explained that she was given the freedom to light each scene, so the references were to ensure they were on the same page: “It was like a library we could rely on when we talked”.

Working on black-and-white films

For black-and-white films, Chananun taps into her background in photography, where she started out with black-and-white as well, and which has provided her a keen understanding of tone. She shared: “It is really important for black-and-white films to understand greyscale and what colours turn to which grey. We have to figure out what greys costumes, locations which are actually in colour turn to. Then we compose and light that way, knowing which greys and blacks are in the image. When we shoot, we make it black-and-white from the beginning. We just never look at the colour version.”

Chananun chats with the facilitators, participants and 2020 alumni of the Objectifs Short Film Incubator after the public lecture.

Chananun ended her lecture by reflecting that she finds reading the script for the first time the most fun. After spending up to two to three years thinking about the film daily all the way through shooting and colour grading, she feels proud of it but also finds it difficult not to look at it and wonder what she could have done better. She reflected: “The first time I read the script is wonderful. The last time I watch the film is painful! But the colour grading, sound design, score…all make what I may feel is so-so much better. Everything comes together.”