A public talk by Kamiliah Bahdar for the Shooting Home Youth Awards 2021

The Shooting Home Home Youth Awards, Objectifs’ annual photography mentorship programme for participants aged 15 to 23, included two public talks this year. Read on for a recap of the second of these talks, in which Kamiliah Bahdar shared her tips on what artists and photographers should consider when exhibiting their works.

Kamiliah Bahdar has worked across numerous exhibitions, programmes and projects as curator, organiser, collaborator, researcher and writer. Her first foray into curating was as a participant in Curating Lab 2012, a programme organised by NUS Museum to train young curators.

Having developed an interest in the conditions of art production, she pursued an MA at Nanyang Technological University in 2015 where she wrote a thesis on microresidencies in Indonesia. In 2017, she received the inaugural IMPART Awards for the curator category. She is now beginning a new cycle in her curatorial practice and looking into the role of art in education and visual literacy.

Once you have your artwork and an exhibition space, you have to figure out how it will come together. Kamiliah shared: “You’re not just thinking then about your work’s narrative or themes, or the overarching theme of the exhibition, but also about space. You must consider who the other artists and works in the show are, and think about selection and layout. Also keep the audience in mind: who they are, what they’ll take away from the show, what your message is to them, how they’ll move through the space.”

Kamiliah has observed that in the past few years, artists have been organising themselves to present exhibitions, “working very closely with, or even as, curators — so, exhibition-making is a useful tool and skillset for all artists”.

White Cube Spaces

Commercial gallery spaces are often white cube spaces. As the name suggests, such spaces are typically characterised by “blank walls all the way, very pristine, modernist aesthetics,” according to Kamiliah.

Though white cube spaces have particular history and baggage attached to them, artists and curators enjoy working with them because they are visually “very much blank slates; the artworks exist as autonomous objects within them. You can really craft them according to what you need them to be”. As a result, they are “quite straightforward to work in — you bring in your works, hang them up, and tweak the lighting. These are things you learn onsite.”

“With resources, you can really transform the space, for example by buying shelves to display the works on. But even without resources, with proper lighting, you can achieve a very beautiful display in a white cube space.”

Hybrid Spaces

Hybrid spaces such as Telok Ayer Arts Club, where Kamiliah worked as a curator for about a year and a half, have been emerging in Singapore in recent years. It is a very multifunctional space catering to a working crowd who would visit for meals and meetings, and curating there was challenging.

While in a gallery, a staff member could ensure the artworks are not touched, in such a hybrid space, there is a higher likelihood that “things might happen to the works, so you can’t be too precious about it”.

One also needs to consider the height at which works are hung. They should be hung higher than in a gallery space, in order to be at an appropriate eye level to be viewed by seated diners — and so that food doesn’t get on it. While visitors are dining for a couple of hours, “you might not have their complete attention; their eyes are going to wander”, compared to visiting a museum or gallery where the primary purpose is more likely to view the exhibited art. Because they might be viewing works from a distance — for example, while seated close to the opposite wall — and cannot get up close to a work (if there is a table of diners in front, for instance), they may not be able to catch finer details in the work. Artists may choose works or an exhibition space keeping these factors in mind.

Despite these challenges, Kamiliah deems hybrid spaces “really interesting, because they’re a chance for you to do something unconventional. Consider how you can be very playful in how you activate your work. Within gallery spaces, there are already coded conventions on how to display your work, and certain etiquette imposed on the audience.”

Site-Specific Context

While white cube spaces are “very much blank slates if decontextualised, you can still engage with social discourse wherever it is happening and then bring it within the space”. Alternatively, the context of the space can inform the works exhibited and their presentation — for example, a space like Telok Ayer Arts Club which is amidst high-rise buildings and frequented by “executives, managers, bankers…” is an apt site to comment on the corporate rat race, hustle culture, lifestyle, etc.

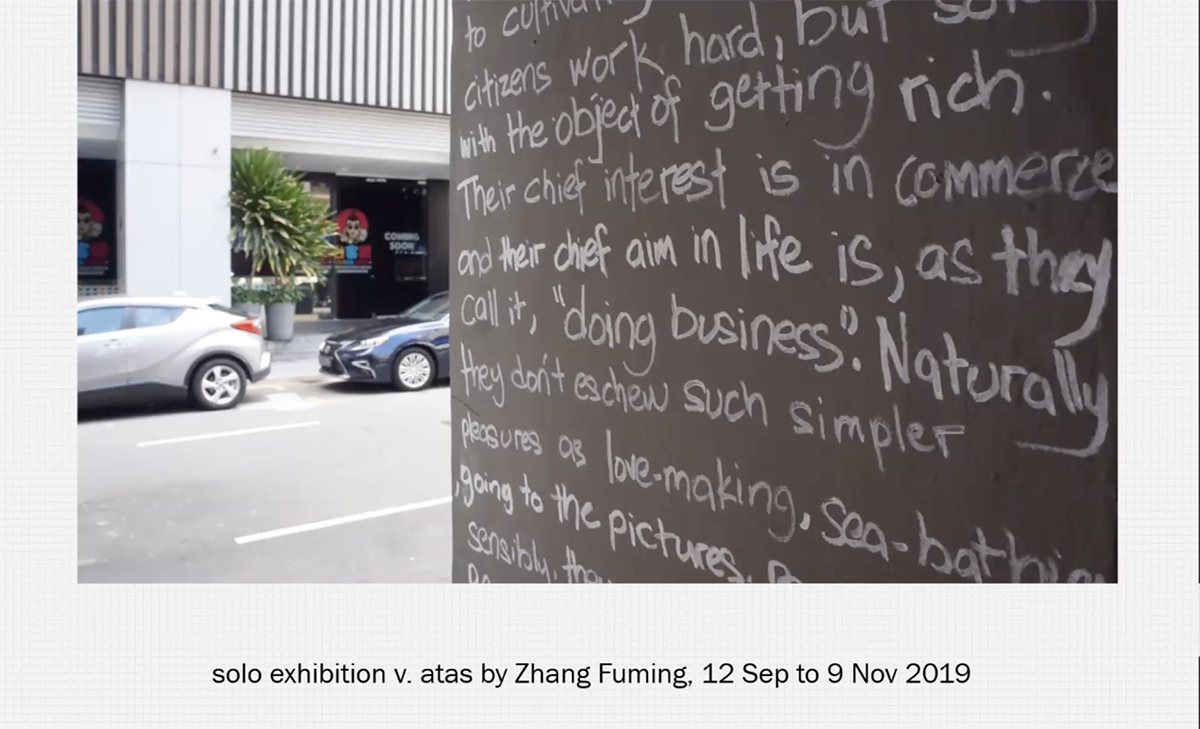

Kamiliah also suggests “using the language of the space” to “find different ways to keep the audience engaged and point them towards the artwork”. Examples from shows she has worked on include: using chalk to write out key text relevant to the exhibition on the space’s walls, paralleling the way food and beverage menus write our their specials in chalk, so that it is more immediately visible to diners; printing zines and placing them with utensils and napkins akin to menus that diners would pick up to browse; and creating card games to spark further conversation about the works.

Unconventional Independent Exhibition Spaces

Kamiliah also highlighted independent exhibition spaces in Singapore that are unconventional in form and nature, and/or in the shows they present.

I_S_L_A_N_D_S is an experimental platform that currently takes the form of a small, empty shopfront unit in Excelsior Shopping Centre. Audiences would be looking at the works within from behind a glass wall, so a consideration when exhibiting in this space would be how to get their attention. The works exhibited in this space are typically installation works, presented with a lot of texture to cope with the space’s depth.

In its previous form, I_S_L_A_N_D_S used bulletin boards along a walkway connecting Excelsior Shopping Centre to another old mall, Peninsula Plaza. Many of the works exhibited in that space used cloth as a backdrop to “create more interesting texture”; in contrast to the shopfront space’s depth, the bulletin boards were of course quite shallow. The works exhibited there were often quite repetitive in nature too. Excepting audiences specifically there to view the works, the others seeing it would be passers-by such as shoppers and workers moving through the walkway. Kamiliah observed: “Each time they walked through, they’d see the same work again. So it reinforces itself. It’s really trying to engage a particular audience that’s moving. Artists have made amazing works with these kinds of constraints.”

FOXRIVER is a mini gallery “about the size of a box that’s maybe 60cm x 60cm”. The gallery — ie. the box — is remade for each exhibition. While photographs of the space are misleading, making it appear life-sized, the gallery has even been remade inside a freezer, for example, for a show in which the works were made of bacon. Kamiliah reflected: “The gallery exists on Instagram as well as in real life. You can go visit it, but in many ways it’s also meant to only exist as a photo”.

Robin is another recently introduced platform that like FOXRIVER “is a very temporal exhibition space — it hops onto existing spaces and then disappears”. Currently, they show works by artists within the space of a camping tent, which offers what Kamiliah deems a very intimate experience.

Kamiliah advises considering “how you can really amplify the subject of your work in the space you’re working”. For example, “if you’re working on something really intimate, if you really want someone to get very close to the work, or it deals with ideas of finding shelter, how can you amplify those ideas in a space like Robin?”

Curator-Artist Working Relationships

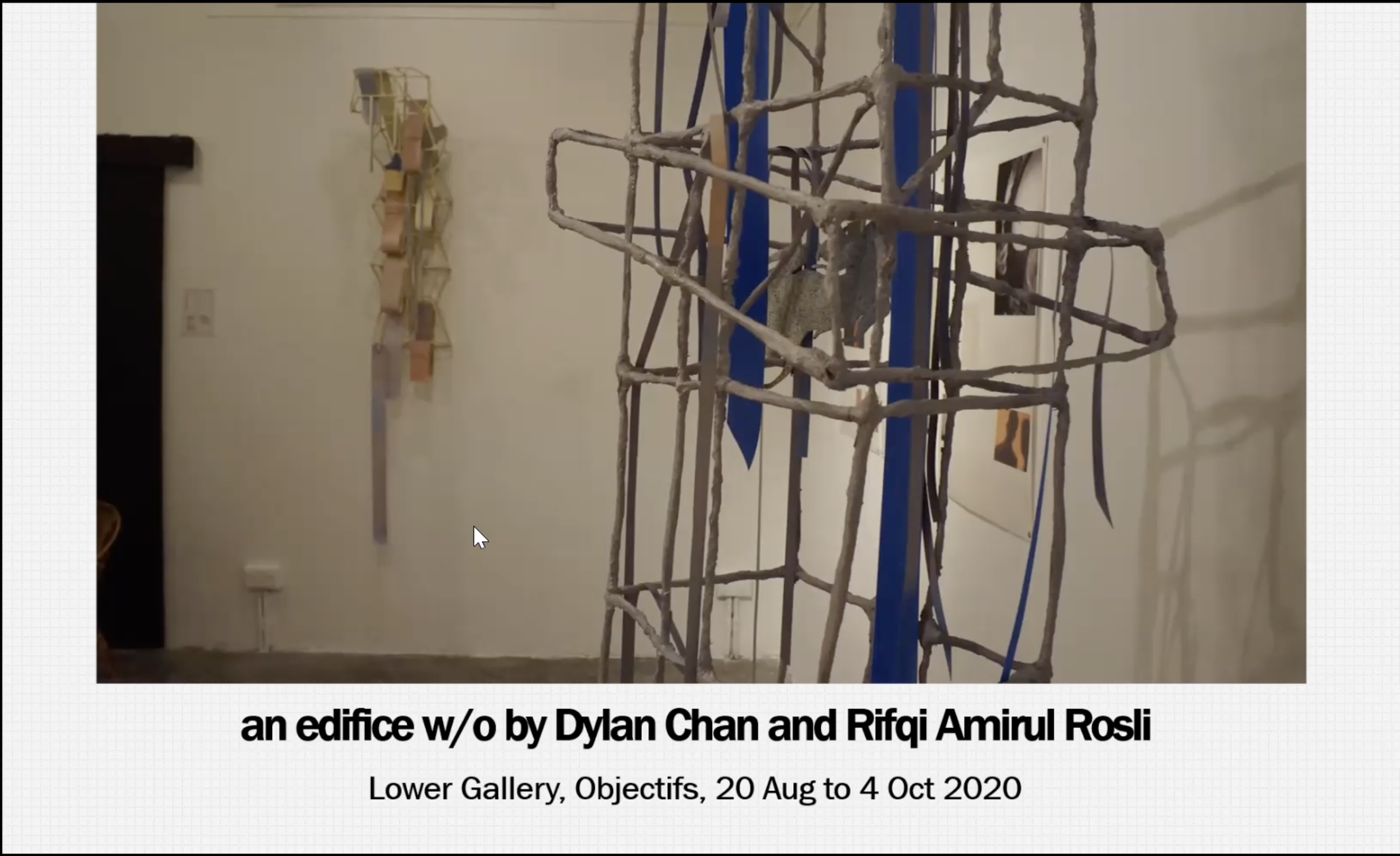

Kamiliah used the exhibition an edifice w/o, presented in Sept 2020 in Objectifs’ Lower Gallery, as an example of a meaningful collaboration as curator with two artists, Dylan Chan and Rifqi Amirul Rosli. Dylan Chan works with photography and has since ventured into sculpture as well, while Rifqi works in sculpture. Though their mediums and works are very different, Kamiliah felt that “both their works deal with subjects that wouldn’t coalesce into something very material; they are examining experiences but always capturing them in a way that it feels almost out of your grasp, very ephemeral”.

Right from the start, Kamiliah made sure that both artists understood each other’s work deeply and what they were trying to say with it. “Throughout the process of putting together the exhibition, they were very much in conversation with each other. In the Lower Gallery, the works still remained very distinct. They didn’t occupy discrete spaces, but also didn’t overlap.”

“It might seem like it’s the curator’s role to create this overarching narrative and form connections between the artworks. But if you have the capacity for it and there’s ease of conversation between the artists, you should really try to facilitate talking about each others’ works, and find ways as a group to bring your connection to the exhibition space.”

Elaborating on this, Kamiliah shared in response to an audience member’s question about the changing role of a curator: “There have always been self-organised exhibitions by artists such as The Artists Village. But when I first started curating in 2012, it was usually the case that the curator would be the authorial voice. With a group exhibition, there is obviously a sense of hierarchy with the curator as the author.”

“But now, I feel like I can work a lot more collaboratively with artists. For example, I prefer to say that an edifice w/o is not a show curated by me but by me and the artists in conversation. So what’s definitely changing is how we create a working process that’s a lot more collaborative. Our work is more horizontal, flat…working together.”

Kamiliah’s process as curator starts with deep engagement with the artists and their works, and making a choice — if available — on the exhibition space. (Sometimes, there isn’t a choice of space but an assigned one.)

She also emphasised the process of editing and selection: “Editing is incredibly important. Sometimes, as a curator you can get overly excited and want to show everything by that artist. You may want to show their earlier works as well to show how they’ve progressed. But sometimes the best choice may be really simple: a concise, coherent and tight selection of work that is just enough to give the audience an impression, and to tell the story you want to.”

After selecting the works, “map their layout within the space. Think about how the audience can — or how you want them to — move through the space. Do you want to go for something linear and chronological or mix it up? Scale and texture are also important to make the show more dynamic.”

While Kamiliah “always starts with the artists, sometimes you also find inspiration in strange places. [She is] sometimes very taken with something [she is] reading, such as Anaïs Nin’s writing for an edifice w/o. There are so many different ways to tease out what an artist is saying, but what you want to highlight can be informed by whatever you’re reading, whatever’s on your mind.”

Writing Exhibition Text

Having written press releases for a commercial gallery, Kamiliah is aware of the pitfalls of using “International Art English”. She acknowledges that “visual arts is itself a language. There is no way you can translate everything you want to say into text. The text is a different way of engaging with the audience, so don’t overdo it. Be brief, concise and provide context, but don’t necessarily provide answers. If your work is very context-specific, provide enough to help them navigate it, but keep your writing open enough that they can come to it and read it with what they know.”

Programming

“An exhibition can be quite static. If it runs for a month, people will come and go. An exhibition is also quite limited, unless you do a really big exhibition with many artists, which costs a lot of money and is tiring to work on. You can add different voices and their perspectives to the conversation. Programming can be scaled based on your resources and the space’s capacity to host programming.

For Nyanyi Sunyi (Songs of Solitude) which Kamiliah co-curated with Syaheedah Iskandar in 2018, the curators organised a series of public programmes titled Members Berbincang, styled almost like an indoor picnic, as an informal open platform to share ideas relating to the works. “The idea was to get people to come together to have a chat, talk, hang out, eat… we had spoken word, music, performances, a roundtable discussion. The exhibition featured largely minority artists and we wanted to highlight the diverse narratives even within the group. We felt like the exhibition couldn’t fully achieve that, and wanted to open up the space to others. Programming was a way to do that.”

Sustainability

Kamiliah would like everyone to consider sustainability when putting together exhibitions: “Building panels, framing your work, wall tags, painting…all takes up materials and resources and at the end of the exhibition it all comes down again. Consider in the future how to minimise wastage. As a photographer, you might frame many works and everyone likes nice frames. But (if it’s a commercial show) and the works don’t sell, how are you going to store it? Are there ways you can unframe it and use the frames for future works?”

Agreements and Contracts

Sometimes, you may work with a space that is very fair to your needs, while others may be very inexperienced — they may not have worked with artists and curators before but want to show art as doing so can give them social currency and a bit of edge — or may simply be too underresourced to create a proper working agreement.

Kamiliah suggests: “Always approach working with people in good faith. If things seem unfair to you, don’t be afraid to bring it up. You can say Can we have a conversation about this? I am concerned about [specific clauses]. It can be hard to navigate, but get advice from friends and peers, and don’t be afraid to speak up. When you do so, you’re also helping the artists that come after you.” The Arts Resource Hub has a Contracts section with resources as well.