HK/SG PHOTOBOOK EXCHANGE RECAP

HK x SG - Discussions & sharing artistic practices and photobooks in a weekend

Objectifs co-presented its first photobook exchange with the Invisible Photographer Asia on 1 & 2 Apr 2017. An extension of both organisations’ continued efforts to further dialogue, create opportunities for the exchange of ideas, develop an awareness for artistic practices around Asia and deepen the appreciation of photography, Hong Kong was our starting point for a photobook exchange.

Over the weekend, we hosted a series of artist talks, a mini photobook exhibition, a panel on Making the Photobook and a slideshow survey of works by Hong Kong photographers curated by Kevin WY Lee. We were joined by artists from HK – Chan Dick, Paul Yeung and Doreen Chan and SG – Darren Soh and Chua Chye Teck for the talks and panels.

Here are some of the highlights from the HK/SG PHOTOBOOK Exchange:

(L-R) Paul Yeung explaining his work to students at the book exhibition; Chan Dick sharing his work during his artist talk.

Influences and how they shape our work

Popular culture and other photographers (by way of exhibitions, photobooks and websites) are common points of references for the photographers.

Chan Dick cited Masataka Nakano’s Tokyo Nobody as an important influence for him. As a commercial photographer, he typically works a few days on a project. When he realised Nakano spent more than 10 years working on his series and did not retouch his images, it moved him profoundly. He learnt that one needs patience to create a body of work, and that personal work does not have to be ‘perfect’ like a commercial one. Another influence was Fuji Tamotsu’s A Ka Ri, which encouraged him to leverage on his commercial experience to develop his personal work. When he finally embarked on Chai Wan Fire Station, it served almost as a meditative reprieve from his daily commercial jobs. While he chanced upon his first image, he continued to patiently photograph the fire station and its ongoings for more than 15 months, spending hours on end to understand the space and wait for the right moment.

Paul Yeung, on the other hand, draws from a wide range of influences – Zhuang Zi’s wit, Stephen Chow’s humour and Martin Parr’s satirical images. He believes “you shoot what you are” and what you are most interested in. He is curious about orchestrated events like beauty fairs, trade expos and flower shows and frequently attends them for fun. Photography becomes a way for him to explore the excess and absurdity that goes on at such events.

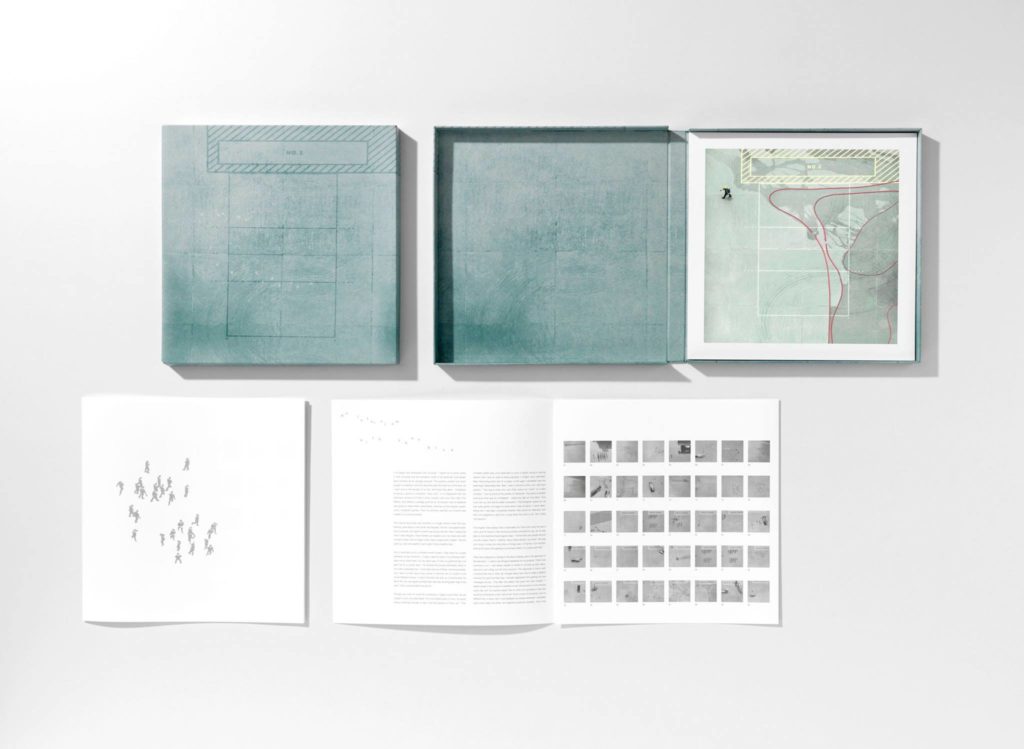

Photobooks as objects

Photographers produce photobooks for different reasons. Some are drawn to the tactile and physical form that allow readers to appreciate the works at a slower pace, unlike viewing works online. Photobooks allow for deeper engagement and control over how the viewer ‘consumes’ your images (e.g. through sequencing, pacing and the design). A photobook also allows an artist to leave behind a photographic legacy, that can outlive his/her lifetime. Kevin felt that you need “currency to get your work shown – be it social or financial”, and photobooks are an affordable solution. But all the photographers agreed that photobooks should be regarded as an object in itself (rather than, say, a mere extension of an exhibition).

Chye Teck gave an analogy of a short film vs. a feature film, where you might be dealing with the same footage. However, how you cut it and re-order your work are completely different and should not be a pure documentation. Photobooks are a “language in themselves”, from the choice of ink, to the type of paper, font, paper coating, ordering of images, folds etc. Thoughtful consideration goes into its making, as it affects how a reader feels and responds to your work.

As a visual artist working in different mediums, Doreen asks herself each time which is the best medium to use, to tell a specific story. Some works are meant to come together as video art, some in print or even to be seen just once on social media as a stream of consciousness.

Different paths to fundraising for your photobook

Grants/awards: Chye Teck received the National Arts Council’s Arts Creation Grant while Chan Dick won a competition with Asia One Books and received an award to produce his book.

Crowdfunding: Paul crowdfunded for his book Yes Madam, Sorry Ah Sir. Because of the political climate in Hong Kong and potential sensitivities of his book, he worked with a publisher in Taiwan. This turned out to be a cheaper option for him, than if he had made the book in Hong Kong. Darren sold prints in various sizes and editions to individuals, using Facebook as his main publicity platform. Both felt that crowdfunding allows people to “buy into” your work earlier, and feel involved in its production.

Individual/Corporate Sponsorship: Darren also raised funds from various individuals and corporates, building on relationships that he had cultivated over the years. He feels that patronage for the arts is important, and one should “never take your supporters for granted”.

Do it yourself: With timing and budget constraints, Doreen did her own design (she is a trained graphic designer) and produced her book cheaply.

“Photography is the easy part”

Edit and selection: Selecting and sequencing images are critical steps in the bookmaking process. Paul made smaller prints and placed them on the floor to edit, while Chye Teck had another artist edit his works.

Design is key for a photobook: It influences how your reader will access your work and how your artistic message is conveyed. For Doreen, the folds of her book’s pages, borderless printing and ‘cheap’ printing were meant to convey the experience of shopping in a supermarket (i.e. excess and choice). Her paper selection and packaging were deliberately ‘cheap’, to reflect the affordability of supermarket shopping. For Chan Dick, each page is an individual print, to be regarded as a piece of artwork. It also gives the reader the same top down feeling that he had when photographing. For Darren, each image sits squarely on a page. This prevents his images from being ‘cut’ by the distracting folds of a book, while offering plenty of negative space for the reader to pause and think.

Get a designer who understands your work: Having the right designer can elevate your work. The ideal situation may be one where you provide a framework and preferences, and collaborate with a designer whom you respect and whose work you understand (and vice versa). In Chan Dick’s case, his designer understood his ‘state of mind’ and the motivations behind his images. He felt that this was key to the success of Chai Wan Fire Station.

Working with a good printer: Offset printing is an expensive process, and those test prints add up. You want to get a printer who understands the medium, e.g. the choice of inks and how long to let the paper dry can affect the final look of your book.

***

Click here for more photos from the HK/SG Photobook Exchange! You can also listen to the Making the Photobook panel discussion on the IPA’s recording here.

The HK/SG Photobook Exchange is a partner programme of The Book Show’s First Draft, exhibiting at Objectifs from 29 Mar to 9 Apr 2017.