Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke and Sarnt Utamachote in conversation

The final Objectifs Film Club session of 2021, presented in collaboration with un.thai.tled Film Festival Berlin, featured Thai filmmaker Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke discussing his short film Red Aninsri; Or, Tiptoeing on the Still Trembling Berlin Wall with Thai filmmaker and curator Sarnt Utamachote, and Leong Puiyee from Objectifs.

Red Aninsri; Or, Tiptoeing on the Still Trembling Berlin Wall is a queer espionage film made in the tradition of Cold-War era Thai dubbed films. A ladyboy prostitute-cum-spy is assigned a mission to disguise as a cis-masculine gay man to acquire important infomration from a student activist.

Read on for a recap of the conversation, in which Ratchapoom and Sarnt discussed the film’s historical aspects, camp and Cold War aesthetics, the intersection between postcolonialism and the notion of queer filmmaking, and more.

The conversation has been edited for brevity.

Sarnt: Colonial borders restrict ways of storytelling. Red Aninsri is an example of historical commonality we share in the region — of the Cold War’s [legacy] but also in the present moment. What does it mean to define our own queer cinema in the region? How do we differentiate from the “Western repertoire” of queer cinema? Ratchapoom, could you explain your background in filmmaking?

Ratchapoom: I studied filmmaking at Chulalongkorn University in Thailand. I read many books in high school, and expanded my interest from reading to films. Finishing a film is easier than finishing a book! There was a film club called Film Lovers in Bangkok which screened obscure foreign films. These were pleasurable, very formative years of learning about cinema. I watched these difficult, obscure films before I watched the canon. Normally, when we discuss the history of world cinema we’d mention American filmmakers like Scorsese, Coppola… but I watched these so much later in my life that they didn’t influence me as much as the ones I watched earlier did. If it was a different film club, it would’ve influenced me differently.

Sarnt: Your three short films are like a trilogy of your way of thinking. There’s a line that literally connects all of them and makes watching Red Aninsri a completely different experience. Could you expand on this?

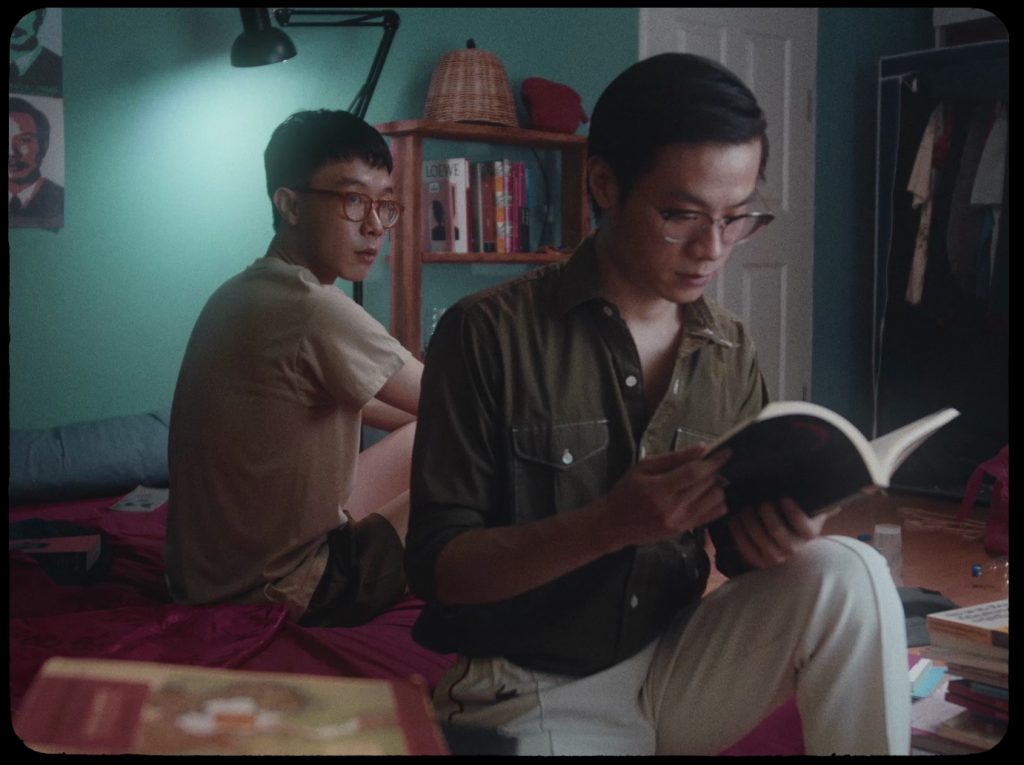

Clockwise, from top left: Leong Puiyee, Sarnt Utamachote and Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke

Ratchapoom: I became interested in postcolonial issues a few years ago due to the political situation in Thailand. When I was young, Thailand was quite peaceful. It was not messy and was quite a stable place to live. As I grew up and was exposed to alternative historiography, I realised what seemed peaceful and solid has another side to it.

One of the biggest myths about Thailand is that it was the only country in Southeast Asia that wasn’t colonised by Western powers. Any book about Thailand says this within its first three to five pages. Kids in my generation were raised with this myth. Every year this kind of discourse was repeated: “Thailand was so great because it wasn’t colonised.” I later became exposed to alternative explanations about this part of history. I felt it could explain a lot about what I found wrong about my country.

I wanted to discuss this in my short film. I always use characters from popular culture from other media. In my first short film in the series, La Double Vie de Maniejan (2013), I used a character from the most influential anti-colonial novel in Thai history, in which a girl from the present time travels 200 years ago to the 19th century, when Thailand was threatened by the French empire. She saves the kingdom and finds a man and lives happily ever after in the past. She doesn’t return to the present because she is so infatuated with the glory of the old Thai kingdom. I tried to reinterpret this.

My second short film Anna and the Prince (2014) features the character popularised in The King and I and Anna and the King. According to formal Thai history, Anna Leonovens came to the Thai court to teach the prince and princess English. She is perceived as having exoticised Thailand as a barbaric place to sell her book to a western readership, In her memoirs, she implied having influenced King Mongkut’s son to abolish slavery during his reign, which Thai people refute [believing he did so in alignment with his own values]. I twisted the story in my film, having Anna return to contemporary Thailand and seeing that this idea still exists in some perverted form.

Red Aninsri is set in Thailand during the Cold War years. The theorist Benedict Anderson referred to this period as “the American era” because Thailand’s sovereignty was compromised by the presence of Americans, which shaped the country politically and culturally. They set up many military camps in parts of Thailand and any parts of Bangkok were turned into recreational centres, clubs, massage parlours… lots of prostitution was going on. The authoritarian, military Thai government at the time got rich off money from the Americans to “develop” the country.

Sarnt: It’s fascinating what you’ve researched. Something that hits you in the face from Red Aninsri is the dubbing techniques. During the Cold War period, America imported so much propaganda but also American films. They needed to use dubbing so that people in the region could understand them.

Ratchapoom: In Thai genre films popular in the 1980s, each character type required a different type of voice. A hero needed to be very handsome and to have a very masculine voice. A heroine’s voice needed to be very feminine and elegant. Sometimes the actor couldn’t do the required voice, so voice actors would do the job.

When the use of dubbing stopped, audiences had the jarring experience of watching their favourite actor use their own voice for the first time. Sometimes, the actor couldn’t use their own voice convincingly, which came across as even more fake than when they used dubbed voices.

I was interested by this: what if a hero insists on using his real voice, even if it’s weak and not masculine enough? It may be a pessimistic view, but — his real voice is still governed; he has to speak according to the script given to him.

There were also logistical reasons why dubbing was popular. Thailand was very poor after World War II. Filmmakers couldn’t afford any equipment, so they just shot and fixed in post-production. Yet, the 60s were considered the golden age of Thai commercial cinema. In the star system, an actor would shoot many — even five — films in a single day. He didn’t have time to study and memorise the script. He would just stand in front of the camera, and repeat the lines that someone fed him. Actors tended to play the roles according to their typecast.

Sarnt: apart from the formal level you also have the narrative structure. The film completely changed when they started using his advice. They stopped ‘dragging’ and it becomes almost completely another film about the conditions of…People usually tend to associate using your own voice with a sense of authenticity and freedom, and you have twisted it around into a a state controlled exercise of “freedom”. How did this come to be in the editing process?

Ratchapoom: You could not avoid or escape state control. Coincidentally, the Cold War and the use of dubbing technology stopped at around the same time — in the 90s. But the mentality formed during the Cold War era in Thailand has persisted into the contemporary years. The old military officers still fear communists and use it as a threat: Student protestors are advised not to be “fooled by the communists”, though there are no influential communists any more in the country. The government can still control people and propagandise their own values. I’d like to explore the persistence of this mentality among the ruling class as they try to maintain their own power and the status quo in Thailand.

Even with the use of one’s real voice, total freedom still isn’t possible. The future isn’t that hopeful but we can experience small happinesses, like the presence of another person that we love and want to be with. Sometimes I wonder if I’ve ended the film too hopelessly.

Sarnt: When we screened Red Aninsri in Berlin recently, everyone was laughing not because of the formal techniques but also because it made comedy out of dating life. There was a scene where the main character said, “I will confess that I’m a bottom and not just a spy.” It’s a wordplay in Thai that comments not just on politics but also on the performance of gender roles in society.

Ratchapoom: It’s more about the humour for me than intentionally wanting to explore gender, though that’s also important in the film. In this film, a transgender person pretends to be a cis, gay male. I wanted to reflect how people our age think about sexuality. It’s not just binary — men and women — but there are more nuances in terms of gender. Even if you are biologically male, there are so many possibilities you could be with the body you have right now. I want to explore and look at this kind of disguising, pretending in a new, more layered way.

Puiyee: Why did you decide to have your two main characters be genderfluid? Did you want to comment on gender identity mixed with the current political situation?

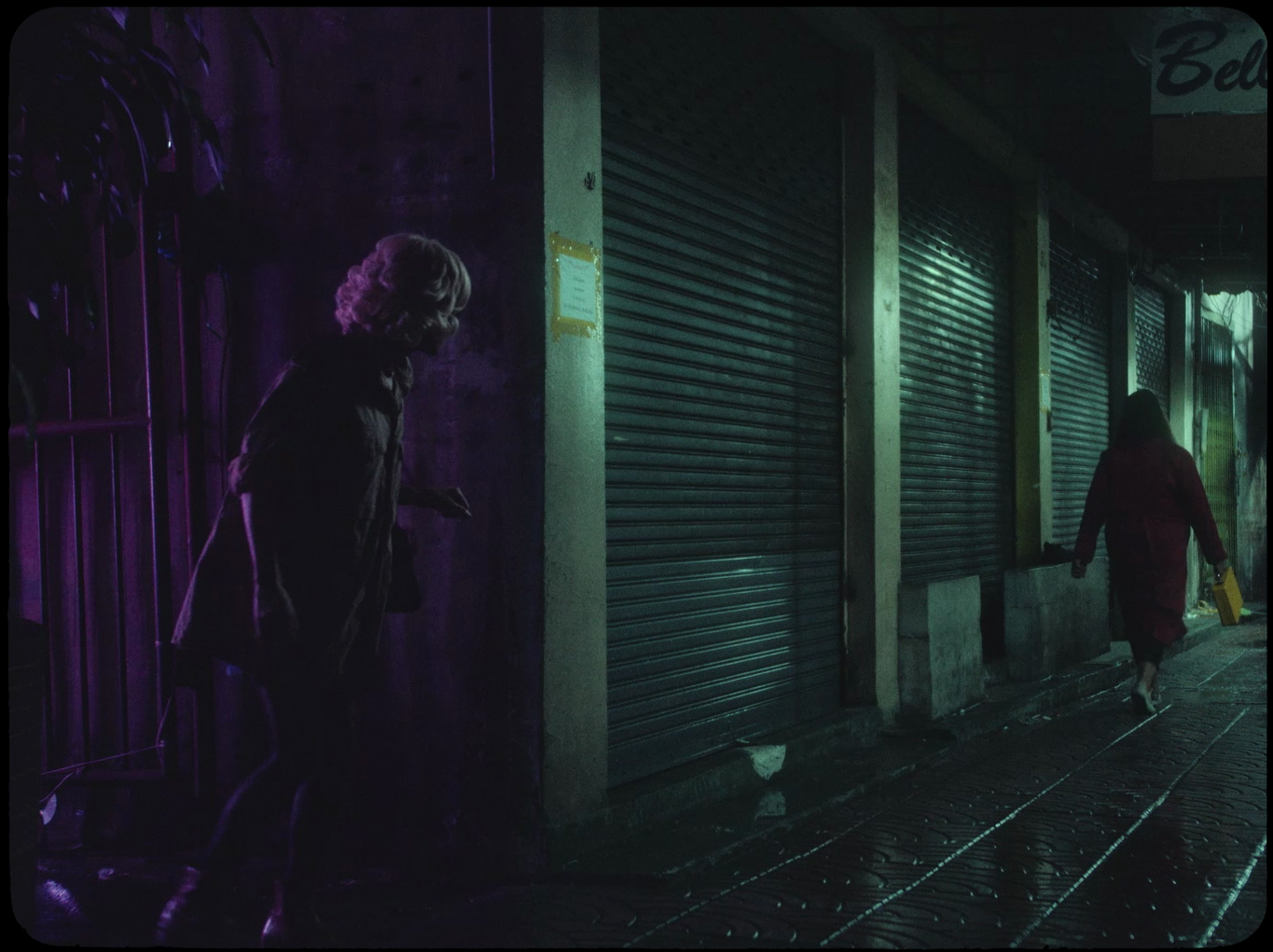

From “Red Aninsri”

Ratchapoom: The characters’ gender identity is not directly linked with the film’s political aspects; it’s more like two separate missions. I wanted to discuss politics but also represent another facet of gay characters in Thai media. Thailand is famous for boys’ love series which are like fan service; sometimes the main characters do cute nonsense. That’s the main kind of representation we see on Thai television. Some people enjoy that. I don’t mind, but there are also other types of gay people and queer people in the country.

I made them gay not just because I am but also because the thriller or spy genre is always reserved for straight characters. Gay characters appear in a limited range of stories: romantic comedies, coming out stories, traumatic experiences… and they can’t appear in action films without being laughed at. Gay action films are very corny. It was important to me to make my characters queer and to have them discuss not primarily sexual or identity politics, but class and national politics.

Puiyee: Towards the film’s end, when the characters use their original voices, there’s a line something like “We were not able to use our voices, but now we can”. Did you want to make a point about what the younger generation of Thai people feels about the current situation?

Ratchapoom: The line is something like “We could use our real voices, like a foreign film.” Thais of the younger generation feel like we’re lagging behind, like the world is going in the other direction and we follow but the distance [between them and us] keeps increasing.

Using our real voices, being authentic to ourselves and having freedom of expression is supposed to be the norm. Everyone should be at this standard, but sadly, we feel the world has already beyond on and left us behind. We hope that one day we can be at the international standard.

Sarnt: There are parallels with the Singapore government disallowing the use of dialects on television.

Puiyee: We were discussing earlier whether it’s common for our films and TV content to be dubbed. In Singapore, content in dialects like Cantonese, Hainanese or Teochew…even commercial films from Hong Kong…have to be dubbed in Mandarin. The only allowances made are for films for festival purposes. So many nuances in language that are hard to translate are lost. Besides your film, are there newer shorts and features trying to pay homage to dubbing? Do they want to make a certain point?

Ratchapoom: Nowadays people look down on that tradition. It’s like a remnant from a past era, considered obsolete and old fashioned. The ways the voice actors delivered their lines was melodramatic and exaggerated in every possible sense. And the dialogue was written so melodramatically; people don’t say such words in real life. For example, I watched a film in which the main character caught his wife having an affair. He asked her, “Do you like swimming in the semen?” Why would people say that?! It’s so harsh. It’s a mean thing to say. But it’s okay in the film.

On TikTok now, kids make comedy out of these dubbing techniques. They aren’t trying to make a point but are simply having fun covering this old Thai dialogue. Thai screenwriters don’t write like that any more. It’d be considered very unrealistic, and old-fashioned in a bad way.

Puiyee: When your two main actors were reading the script, was it difficult for them to get into character, saying such exaggerated lines?

Ratchapoom: My actors’ acting is very stylised and not intended to be realistic. One of the first things I said to them during rehearsals was “don’t be human”. No matter how well you act human, some will find it unconvincing. I set up my own game and rules, by which the audience has to judge the acting rather than their own point of view. still aim for emotional authenticity. It needs to feel real, even if it doesn’t look real. My actors are theatre-trained, so they are trained in such techniques.

Audience Member: What are your views on the larger movement of decolonisation, or historical reflexivity within the filmmaking communities in Thailand?. When we discuss decolonisation and postcolonialism in academia in Thailand, the conversations often start with literature, and kind of stay there in my view. I think it’s changing now with Apichatpong, Ratchapoom… is there anyone else

Ratchapoom: Filmmakers from the northern regions of Thailand, like Chiang Mai. There’s a young filmmaker who is Karen and grew up in a refugee camp. He started making films in school about his experiences as an ethnic refugee, and they were so powerful.

There’s also a film community in northeastern Thailand which wants to discuss their experiences as teenagers who may not have the opportunity to study or live in Bangkok. They want to discuss their experiences from their own point of view because usually when the film setting moves outside Bangkok, it’s still always conditioned by the Bangkok perspective. These filmmakers from are trying to tell their own story, not even to be political, but their existence or presence is already political.

Films like Apichatpong’s and mine are examining the past, but most of these regional filmmakers are discussing the present: their lives, their struggle, the issues they’re dealing with. Such films could be viewed as postcolonial as well.

Sarnt: “Being political” and “doing political” are two different things. In our festival last year, we focused on minority groups and showed films from the southern part of Thailand, and northern ethnic groups like the Shan. We discussed how you need time until local, non-centralised filmmaking scenes develop into something “sophisticated” or for the European market. In the beginning, it’s always something local and for the community. It’s about supporting communities in speaking in their own voices. Reaching the international market is not the same thing; it’s the next question. It’s about allowing them time and opportunities.

You can also read our past Film Club recaps here.