By Carlo Francisco Manatad for the Objectifs Short Film Forum 2021

The Short Film Forum, part of the Objectifs Short Film Incubator 2021, saw film-makers and film-lovers from all over Southeast Asia tune in to a packed weekend of free online lectures and panel discussions by international industry experts. Read on for a recap of the first session and stay tuned for subsequent recaps on our Journal.

Filipino filmmaker and editor Carlo Francisco Manatad is an alumni of the Asian Film Academy, Berlinale Talent Campus and Docnet Campus Project. His short films have been celebrated widely across prolific film festivals like Cannes, Locarno, Busan and Toronto. His first feature film Whether the Weather is Fine, about the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan on his hometown Tacloban in the Philippines, will have its world premiere at Locarno next month.

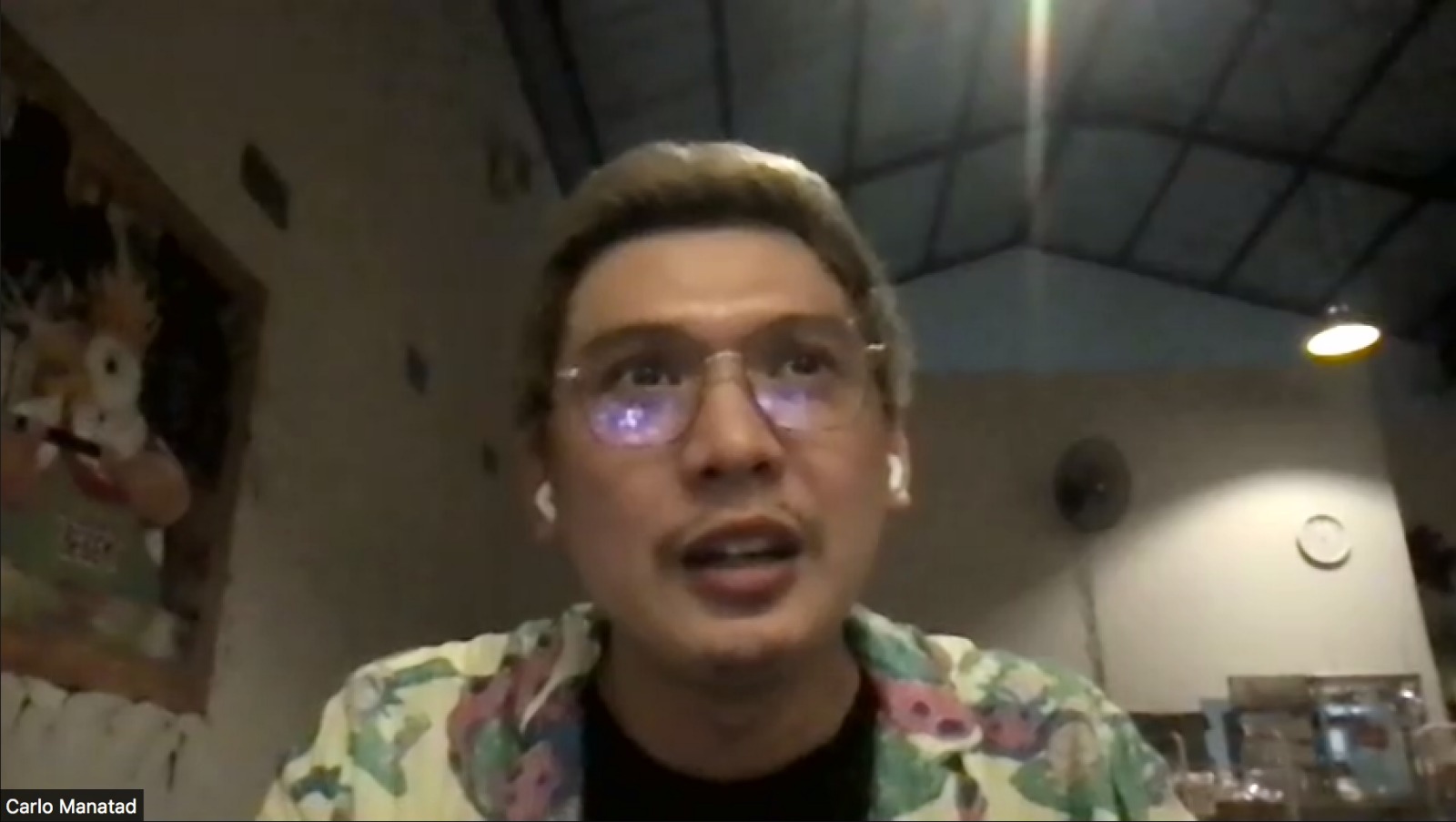

Carlo Francisco Manatad shares his experience making short films.

Carlo began his talk by admitting that his process of conceptualising and making a short film is atypical, because he is aware that writing is not his forte: “My films are always personal. Of course research matters, but in my process, I am more often inspired by unstructured exchanges of ideas, random conversations with my friends, or events I’ve experienced.”

Curiosity and Circumstance

Carlo’s formula — or lack thereof — for conceptualising a short film could perhaps be described as curiosity + circumstance.

For example, Fatima Marie Torres and the Invasion of Space Shuttle Pinas 25 (rent it here), which depicts an ordinary old suburban couple’s life on the day the Philippines’ first space shuttle is being launched, was inspired by his curiosity about his elderly single aunt’s romantic life, or its seeming absence. “The core element of the film is how an old person feels about lust and love. I add to this core the elements that I want. I had keywords in mind like love, lust, relationships, sci-fi, low budget.”

What is not possible also shapes his eventual film. He explained: “I wanted to make a sci-fi film, but I didn’t have the money. I wanted to cast older people, but I didn’t have the money to cast actors. I wanted to shoot the film in just one day with friends, so I knew the easier the shoot, the [more viable it would be].”

Strategies that were initially employed primarily as practical responses to the prevailing circumstances also turned out to give the film its distinctive sense of humour. Carlo’s actors in Fatima had mainly played extras or background talents and were not experienced in memorising lines. Carlo responded by spontaneously asking them to speak gibberish. As he was clear about the intention of each scene, while editing he added subtitles that would reflect what the characters would say. While editing, he pushed this playfulness further by using Japanese and Bahasa songs. “Language became a big element in the film, though it started as a joke.”

With his first short film Junilyn Has (rent it here), circumstance came first. Carlo and his friends wanted to make a short film each week, just for fun. His friends already had scripts, but he didn’t. When Carlo was about to shoot, Typhoon Haiyan hit his home city of Tacloban, prompting Pope Francis to visit the area. Carlo’s curiosity led him to wonder: “The Philippines being a religious country, would the bad guys be good, at least for a day, during the Pope’s visit? How would criminals work? How about bar girls?”

He recounted observing the seeming reluctance of a very young woman performing in an adult entertainment show in Thailand, and with this film “wanted to go back to the same feeling I had when I was inside the bar: the feeling of observing somebody and being entertained but actually seeing the sad truth of what’s happening”. The resulting short film depicts a dancer in a nightclub who has to learn new moves to attract more customers during the Pope’s visit. As she rehearses, she is also preparing to free herself.

Carlo shared: “My films leave [audiences with] more questions than answers. I’ve worked as an editor for years and my films may be seen as very editing-heavy, but the scenes can actually be [viewed as] very independent sequences. I like to observe. Narratively speaking, even if they don’t make sense, I want my films to leave a certain feeling. I want them to convey what I felt when I pinpointed their core element, and when I was making them.”

Carlo aims to explore something new with each short film he makes. “I want to make films about things that are not made into films. I see a rock, get fascinated by it, and from that point on I want to make a film about a rock. Some would say, it’s lifeless, it doesn’t have a story. But there will always be reasons for what [stories] you want to tell.”

Carlo’s personal preference is for films that do not “fill in all the blanks for the audience but that makes them think and feel” over a perfectly crafted work that offers less room for discussion. He acknowledges that his process may not appeal to everyone. “I try to please myself first; I start with what I find random, or funny. If you’re making a comedy but it’s not funny to you, you might not be doing the right thing.” However, he rejects his films being branded “experimental simply because they’re not understandable.”

“As a filmmaker, you are not required to explain your work to people. How people interpret it is up to them. The most important thing for me is that it creates a conversation, regardless of whether it’s good or bad. People feel something, and talk about it.”

The Political is Always Personal

While many films from Southeast Asia discuss social and political issues like poverty explicitly, Carlo prefers to take a more layered approach. “I don’t want to talk about it just because it exists. I’d rather talk about other things because the sociopolitical structure of the Philippines will inevitably [show up], and it will always be personal,” as he is a filmmaker from the country and his works are set there.

This is how Carlo approached his second film Sandra (rent it here). His curiosity was piqued by a viral video of many girls fighting and bloodied all over, with more girls around them cheering them on. He contacted two of them to ask why they were fighting and was told that it was a weekly pursuit for the girls to strengthen their bond. He wanted to make a documentary but as he was scared to travel to their area — once again, the influence of circumstance — he decided to make a narrative short film about their coming of age. He was conscious that if he set the film in a slum, the story would be one that may reinforce certain perceptions about poor, uneducated girls. But as he wanted to focus on their sisterhood, he deliberately set the story in a mansion.

Similarly, Carlo acknowledged how Jodilerks Dela Cruz, Employee of the Month (rent it here) discusses the circumstances of contractual workers and the issue of extrajudicial killings in the Philippines. But it in fact stems from a very personal story. (Read more about this here in our recap of Carlo’s previous discussion of this film.) Carlo and his crew were doing a location check in his hometown and he wanted them to visit his family’s ancestral home. However, confusion gave way to embarrassment when he simply could not locate it. He called his mother, who informed him that it had been sold, and that a gas station now stood in its place.

Thus, while the film seems to depict anger at the political situation in the Philippines, it is actually about Carlo’s deeply personal reaction to the loss of a place he felt a connection with. “From that core element, I put in what would actually work for the film.”

Carlo suggests the following exercise to help filmmakers conceptualise their works:

“Go out of your house and observe people. Many stories told are of either extreme: the highest or the lowest [in society]. Fewer stories are told about those in the middle, like your neighbour doing their laundry every day. But when you observe fully, you see something more and sometimes these stories are much bigger than what we see in other films.”

Process over Planning

Carlo describes his approach as instinctive, and “more process-based than the usual”. Rather than methodically location scouting, for example, he tends to choose locations on the spot. “I work with what I have. A lot plays in my mind and I put it together. Sometimes you don’t need to explain why — sometimes I just cannot. It’s more of a feeling.”

A lot of Carlo’s process also plays out during post-production: “Sometimes I have bullet points of what I want to shoot. These change based on what I see when I go on set and look at what is readily available. When I get to editing, sometimes the structure changes, sometimes the whole narrative changes.” Recapping how his approach influences his works, he summarised: “My films are much more free in terms of structure. Regardless of what I shoot, it’s a mixture of the mundane and of daily life. Even if you mix it, it will still make sense because there’s the core element. [The process] ends with a holistic view of what the film is.”

In response to an audience member who questioned how Carlo begins to “build structure or tease out a narrative in [his] edit given the flexibility of [his] process,” Carlo reiterated the need for the filmmaker to “know at least what the film wants to say, or what kind of emotion the film wants to evoke in viewers, and build the structure from that”.

That baseline of certainty about the film’s core empowers him to “become more spontaneous when I’m on the set, because I’m already confident of how it should be. Know first what your intentions are and what kind of film it is, and then you play on the form, the structure…” His ample experience as an editor has also trained him in “not being emotional about cutting scenes. Don’t be too emotional about how it was written and shot, but consider how it fits into the bigger picture. Prioritise the film.”

Carlo chats with participants of the Objectifs Short Film Incubator 2021 about their projects.

Carlo ended with these encouraging words for the audience: “Each short film I make helps me realise what kinds of films I want to make. I develop a more precise and distinct voice and [refine] the process I want to have. Filmmakers have to become more aware of the process they’re most comfortable with. Mine may not work for you. The usual approach may not work for you. So try to find that process. It takes experimentation. It took me five short films to know which process [works for me].”