Sookoon Ang and Silke Schmickl in conversation

Exorcize Me is a photography, videography and live performance project addressing coming-of-age anxiety and teenage alienation. In November 2020, the Objectifs Film Club featured Singaporean visual artist Sookoon Ang discussing her film Exorcize Me with curator Silke Schmickl in November 2020. The following conversation has been slightly paraphrased for clarity and brevity.

Silke: To start the conversation, we will focus on the context and subject matter in the making of Exorcize Me, and then go into other themes we thought would be interesting, like distribution, how this work exists in varying contexts in different parts of the world, and the experiences that came with displaying the work.

Sookoon: Exorcize Me was created during The Art Incubator Residency that was supported by Objectifs in 2013. At that time, I had a desire to reach back to my past… to explore the idea of coming of age – the wanting to get rid of the insecurities and unease that are associated with being a teenager. I reached back to that time because I recalled that it was the beginning of my existential anxiety. I wanted to talk about the difficult metamorphosis between childhood and adulthood. With Objectifs’ help, I was able to reach out to some schools and students.

Silke: You were already in your 30s when you made the film in 2013. Do you remember what triggered this sudden desire to look back in your teenage years?

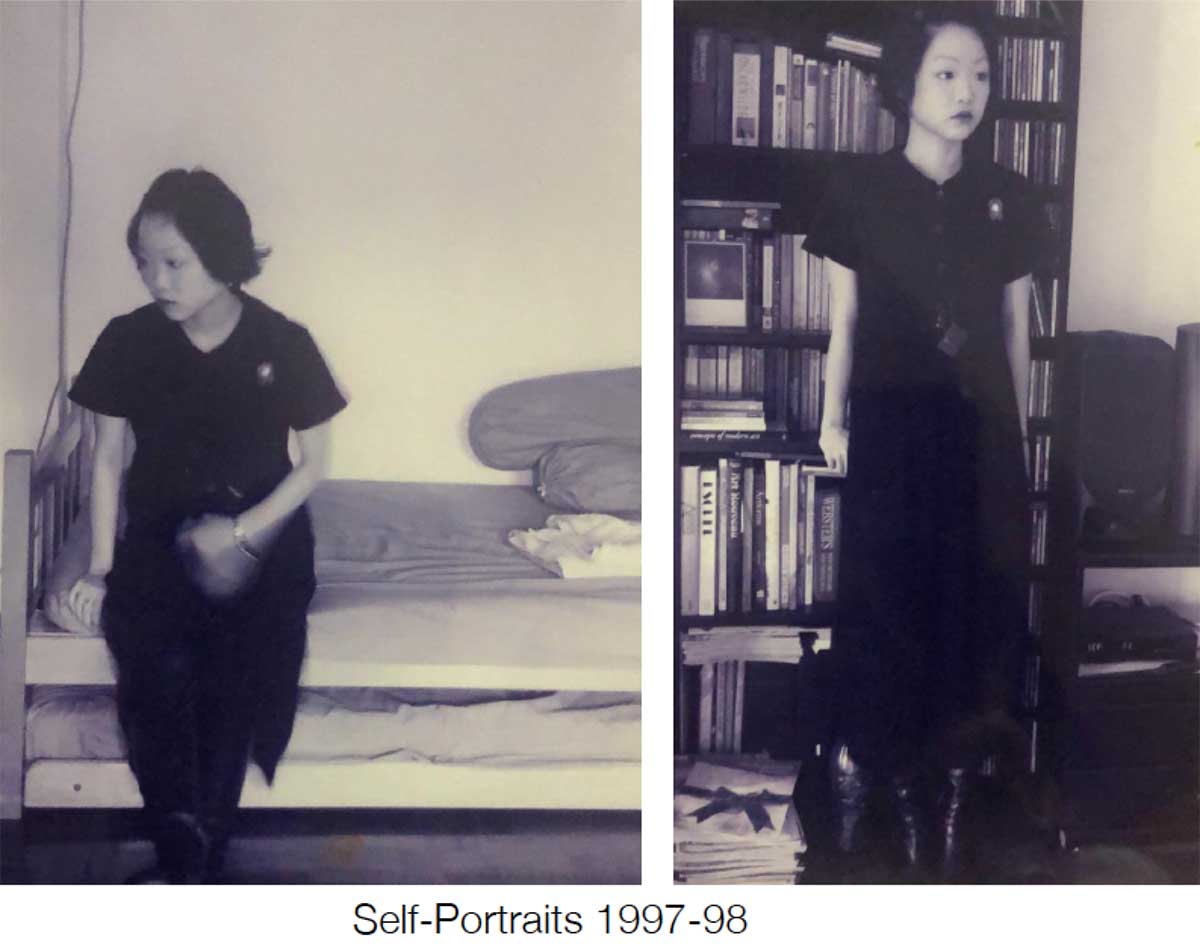

Sookoon: I was living in Brussels at that time, and it was quite dreary. I was feeling quite depressed. I’ve always had to deal with an existential anxiety, which is one of the reasons why I’ve had an interest in things that are gothic. Here’s a self-portrait when I was in my 20s taken in film… the stage of growing from a teenager into adulthood, with a growing sense of existential anxiety.

As a teenager, I was interested in depression. I read The Bell Jar, Girl Interrupted, Prozac Nation… books that had to do with the idea of the interior versus the exterior world. This extended to my artistic influences as well. That has remained constant in my life. I thought then that I wanted to bring it back into my artwork.

In my work, I usually avoid representing humans. It’s not something I am really interested in. But for this work, I didn’t see any way around it, and it’s one of the few pieces that I have a direct representation of people and people in situations.

Silke: What I’ve always loved about Exorcize Me is how you’re really within the work. It feels like you’re totally there and your perspective comes out in such an authentic way.

It is interesting that you made this work when you were at a different period in your own life. You were already a practising artist who had shows all over the world, in your early phase of establishment as mid career artist… but having this kind of sensibility coming into your work.

Now seeing your pictures from the 90s, when you were a student yourself and how you depicted yourself, with a kind of isolation and anxiety that comes across in Exorcize Me… It’s beautiful to see how years later, you could translate this into something authentic, strong and poetic.

Sookoon: This has been something that recurs in my work. I explore themes and then years later, as I mature as an artist and when I feel like I have a different perspective of what I can do, I revisit and recreate certain things that motivated me to do them in the first place. Not just technically, but conceptually as well, and how I create, in what I hope is more expressive and poignant then when I first encountered the subject.

Silke: How did you work with the girls in Exorcize Me? It feels partly documentary and authentic, while being extremely staged.

Sookoon: During my residency, I was assigned a mentor, Lee Weng Choy. When I shared my idea about working with teenagers, he suggested reaching out to the theatre students at the School of the Arts (SOTA). The theatre students are able to be very emotive without being self-conscious.

The students volunteered and I didn’t do any casting, because I was not looking for girls to necessarily fit or look a certain type. The main idea was to talk about this darkness within, and that is not something you can tell by someone’s exterior.

I showed them visual references, like Balthus. The girls and ambiance in Balthus’ paintings remind me of my own teenage angst, and the lethargy that grew out of my depression and anxiety. The girls in the paintings appear to be lethargic and self-absorbed characters immersed within their own interior world. This was particularly what I remembered, as a teenager, when I was depressed. I could lay in bed all day, just sitting around staring at the ceiling or doing nothing.

As a teenager, I was very self-absorbed, and thought people around were talking about me or judging me. At the same time, I would think my thoughts were so original, or that my taste or clothing was unique, and that no one could possibly understand the profound poem that I wrote in my notebook. And of course it all seems quite ridiculous now, but it was very serious at that point. I wanted to revisit that the idea of being self absorbed, but also the difficult world that teenager experiences.

When I showed them these visual references, the students understood what I was trying to do very quickly. I think it’s their intelligence, but also their theatre training. They could capture that feeling immediately, and needed very little direction. They could reach into themselves and pull out that sense of loss and darkness that I was trying to tease out in my work. It was such a wonderful experience to work with them, especially since it came across so authentically.

Silke: It’s interesting that the video itself has no dialogue. So everything is acted through the body, the poses, the make up – which is why I’ve always thought it has documentary qualities because it feels so real. This for me has been one of the strengths of this work, how you as a director managed to get this across.

I think this also explains the success of the work. I had showed it in Paris and Beirut as part of a Lowave programme called Body Politics. We also showed it at the National Gallery of Singapore in The Woman is the Home. That’s Where She Used to Be… And this work always stood solidly among the other works from around the world. I think that certainly stems from the authenticity of the film and the work you did with the participants involved.

Having this experience of growing up and having these anxieties, it also uses the body as a formal language that goes beyond this particular period of your life, and also the cultural context in which you grew up. While we recognise Singapore in the film, I think it also has forms of abstraction, which explain why this film is so well received wherever it is shown.

Sookoon: In the context of Singapore, as you can see in the girls with their uniform, there is this idea of conformity. While we are individuals and there’s a desire to express something non-confirming, that is frowned upon in Singapore. As a teenager, I tried to express it in the way I dressed, like dressing as a goth or writing poetry even though no one was about to publish it. So the work was informed by my upbringing and experience growing up in Singapore.

Silke: Most of your works have a subversive undertone, and really challenge conventions, whether it’s in the more figurative form, like in this work, or in your abstract work.

What always stands out and is present, is a certain duality, and I think that is also something very remarkable about this work. On the one hand, the actors are young, and they have their lives ahead. It’s this youthful power of their bodies. On the other hand, they are wearing a mask that already indicates kind of their death or the end.

This kind of tension between two temporalities, the beginning and also the end, and bringing that together in the form of the body, is another really important aspect of this work. Could you talk more about what interests you in these extremes, the sides between the black and white, and the time frames that you’re operating in?

Sookoon: The make up, poses, school setting, and uniforms – they’re all a representation of the overlapping of reality and fiction, the interior world brought out to the exterior. In my work, I’m saying that it’s normal to be dark or negative, not everything is sunshine. To be in the margins and not perfect, and not everything has to fit this glossy veneer we present of our society.

I hope this work can stand the test of time. Like the novels that I’ve read, stories that talk about the human psyche that can transcend through time. Growing pains and existential anxiety do transcend nationality, cultural backgrounds and time.

Exorcize Me at Palais de Tokyo

Silke: Let’s talk about the different presentations of this work. There is the single channel video, but there’s also a four-channel version, and a photography series. I had the chance to see the four-channel installation in Paris and Singapore. They were of a different scale and the immersive experience was fantastic. But I also like the single channel version, because it focuses my attention in a different way, and I look more at the different chapters. How did you decide on these different presentations?

Sookoon: The work was created with a four-channel installation in mind, with the idea of the girls being larger than life. In entering the space, you are absorbed into their world and into their self-absorption. I’m very lucky that this work can translate into different mediums, such that it has worked well as a multi and single channel.

But I can’t take credit entirely because I feel like it’s how the stars aligned for this work. Without the invitation from Objectifs and The Art Incubator’s backing in 2013, it would have been hard to reach out to a school and I would not have found these theatre students. Joe Ng, the music composer who has always been so generous in helping me, made the music free for me because there was no budget. And people who supported the work, like you Silke, or Jean de Loisy who saw it at the Singapore Biennale and decided to bring it to Palais de Tokyo, which allowed me a bigger space to fulfil the potential of the work. And the videographer and photographers who helped me capture the performance. This is to the credit of everyone coming together to help me fulfil this vision.

Silke: What you just said was beautiful. It is very much how a work like this gets made. It starts in a fragile, economical environment with hardly any funding, but happens with a lot of goodwill and a desire to collectively achieve something. How you have approached it… as a curator and spectator, you can feel that courage and collaborative spirit. It’s not simply a commission that you accomplished and sent to a festival.

On the note of collaborations and artistic risks, this was also addressed in your feature film, Living for Art. You were looking at the fragility of these economic systems, and how an artist decides to make a work, even if there’s no funding or production support in the beginning. With collaborations however, as you had for Exorcize Me, there is a sense that we can all do much more together. Can you speak more about how such relationships or even friendships have helped?

Sookoon: I feel like I’m emboldened by people that have helped me. Your interest in my work makes me interested in my work, because I cannot be the only one that is interested in my work. I’m only human and sometimes I look at my work and I think it’s bad, I don’t want to do it anymore.

But the support from people like you and Objectifs give me the courage to continue my practice. And this is what the art community is for. This is why I thrive in my art tribe, because without all this support, I don’t think it would be interesting for me to make work for just myself.

Silke: I agree. I made the same experience when running Lowave and we achieved much thanks to this collective approach.

Hopefully Exorcize Me would be an inspirational example for younger filmmakers or those whose work have not yet travelled that far. I think that it’s also an important consideration for filmmakers, who feel the push especially in the festival world, that you need to make new work every year, and think that you only have one year to distribute it in these festival networks.

Initiatives like the Objectifs Film Library are essential and sustainable platforms for such works. As you mentioned earlier, we often build on works or projects from the past. We return to them and either reframe and reinterpret them ourselves, or experience how others place them in new contexts or perspectives. Providing access to experimental film and video art on such dedicated platforms is extremely valuable for filmic genres that are economically fragile.

Sookoon: It’s true.

There’s so much demand for the new that it’s almost oppressive to any creator, to keep producing something new. Art is not about trend; it’s not quick consumerism. It takes time to mull over it, to take time to process.

Even as a creator, when I finish my work, I might not be able to understand my work itself until a few years late. Then I might see it and realise, oh, the work has that meaning or expression that I was unable to see previously, or that work has nothing now but takes time to simmer.

It’s important not to feel the pressure of making new work all the time or to have an immediate reason why the work has to exist. Experimentation is still very important, especially for young artists, whose work might not be mature yet and ready to sell or to show.

The idea of experimentation and learning about the process of making, looking at your work over and over again, is an important process as a creator.

Silke: How was the response from the students when they first saw the work? And now, as they are older?

Sookoon: One of the girls Melia is in the audience here. She’s in the final year of university now.

Melia: I remember Sookoon suggesting the ways that she wanted us to position ourselves, like the lethargy that she wanted to bring out. I remember that quite clearly as a director’s point.

As you mentioned earlier, it was easy for us to get into that mindset and into character. I guess it was back then, I was 14. It was also a time of personal teenage angst for me. I’m 22 now. That’s not to say I’ve left that behind, but I do understand that I’ve matured since then. But yes, I recall being able to embody that feeling quite easily back then.

Silke: What about the make up? Did you have a choice in how you wanted your face to be painted?

Melia: No, I thought it was already cool to have something painted on my face in such a gothic way. I was already interested to have the black circles and white face. But I think some of my friends had even more, and gave more direction in terms of how they wanted to go about it. Some had teeth that made them look even more jarring.

Sookoon: It was so wonderful to work with Melia and her schoolmates, who were then around 14 and 15 years old. Working with them made me think that every kid should take theatre lessons, because they were so expressive! I remember being so uncomfortable in my own skin at that age, and unable to speak up. Regular school teaches us to be quiet and listen, and not have much personality.

That was how I was for a long time… and I think that didn’t really help me as a professional when I was trying to launch my career. I didn’t know how it could help my art career, and it took me a long time to learn to be articulate and be comfortable in talking about my own work.

Audience Member: What are the ways in which you think this film might be different with actors of different genders, or if it was made in a different generation. Is the experience of teenage angst and envy different across different locations, and is the film received differently in different countries?

Sookoon: Recently here in Paris, I met an art student, who was in his 20s, who reached out to me as he was trying to look for a mentor. He told me that he as as a teenager, he went to Palais de Tokyo and had seen Exorcize Me. He could pick up on the sensitivities of the work, and it stayed with him through the years. So I think the work can transcend age, gender and nationality.

The appeal of the work lies in the fact that everyone has this interior world, which you spend most of your time in. The exterior world is just a part of your time. The work acknowledges this interior world rather than pay much attention to the exterior world… because we spend more time inside our head than outside our head.

Silke: As a teenager, I did not really go through such angst. So perhaps rather than a cultural, national or generational specificity, it’s a personal experience that we might have or not, depending on our own upbringing, context and personality.

Sookoon: I think that it’s not necessarily something that only teenagers go through. I do see it in some of your work now, Silke, and how you are able to express that interior world even in different phases of your life.

Silke: That is true. It’s good that you mentioned earlier, that it’s really this duality between reality and fiction. A fictionalisation of reality that we have that’s stronger in our younger years, because everything is so unknown, and we project a lot.

But hopefully it can also happen throughout our lives, because that makes our reality more exciting. That’s probably why we like art and all kinds of projections of who we can be, and who others can be, and just the story that it also creates.

Sookoon: The idea of this interior world… or just seeking answers within yourself, it’s always there. It could manifest anytime in your life, and not just in your teenager years. When you have to go into yourself to face those shadows.

Audience Member: Are there follow up works from this film?

Sookoon: I have thought about whether it would be interesting to do another rendition of this work… but the film happened also because of the right timing and support from the community. So perhaps some day, I’ll be able to revisit it.

Silke: Sookoon is also a well-known sculptor… and we didn’t talk about this part of your work, but you have explored similar themes as well in your sculptures. For example, different types of Eastern and Western mythologies or philosophies. You have sculptures that are made out of transparent or translucent plastic sheets, and they are filled with air. I feel these kinds of resonances and tension, between reality and the beyond reality is also a form of follow up from these earlier works.

Sookoon: Oh yes. I think while my works look outwardly different, they have the same trajectory of trying to find and negotiate between the real world and imaginative world, the tactile world and the non-tactile world, the physical world and the metaphysical world. I think that is the connection that links all my work in in different medium and subject matter.

Film still from Exorcize Me

Exorcize Me, along with other short films by Southeast Asian filmmakers, is available to rent on the Objectifs Film Library.