A public lecture of the Objectifs Short Film Incubator 2020

The inaugural Objectifs Short Film Incubator presented by Objectifs in partnership with Momo Film Co took place online in Sept 2020 and comprised a month-long mentorship for five projects from Southeast Asia, three public lectures and an online film club featuring the mentors Davy Chou and Pimpaka Towira.

Sherad Anthony Sanchez, a filmmaker from the Philippines, has more than a decade of experience “on the other side of the table, hearing pitches as part of a grant giving body, a producer or a consultant to producers”. He has mentored 400 filmmakers, many of whose films — and his own — have been to prestigious film festivals like Rotterdam, Locarno, Cannes, Venice and Berlin. This recap presents key takeaways from his online presentation on What Makes a Good Pitch.

Loglines: starting your pitch right

At the heart of a pitch is the logline, “a short summary of a film containing all the elements of the story, intended for industry professionals. The logline is the first step to a yes”. One or two sentences will do — avoid run-on sentences — with the goal of hooking people right away.

“A logline tells us how flat, generic or well developed your screenplay is,” Sherad shared. It needs to be short and catchy because sometimes, pitching happens informally, “often over coffee or a cigarette. There were times I pitched my loglines five times a day, purely by accident.” Do not deal in abstract statements, which “may work in a gallery or museum setting”, but “producers want to visualise as quickly as possible”.

Sherad advises quickly crafting a logline at the start of a project, even before a script is ready. “I use loglines to ground myself. When developing the script, I don’t resist if I’m moved in a certain way, but I at least have a foundation and I’m not starting out with a blank page.”

“Where there is tension, there is movement.” Always create or find tension in your logline. “You can use two opposing adjectives or juxtapose ironic elements against each other. For example, an aquaphobic sheriff has to deal with a shark — an authority is rarely introduced with his fear.”

The anatomy of a logline

By Sherad Anthony Sanchez

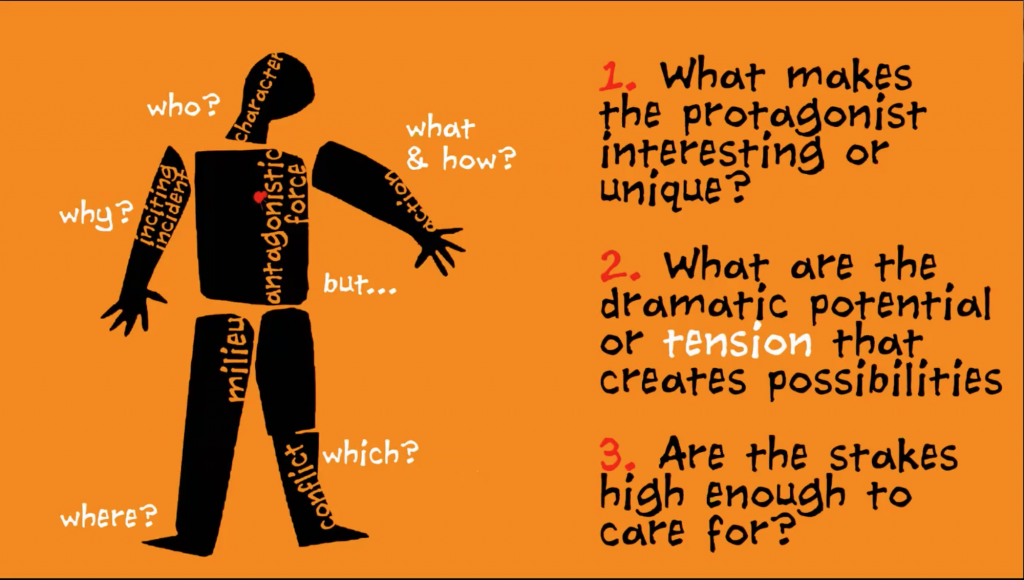

The four major elements of the logline are:

1. a character

2. an action

3. an antagonistic force and

4. an inciting incident.

1. The character is the who. “Introduce them with ironic adjectives if possible — for example, a cold-hearted doctor, a group of murderous medical students — as these show their already inherent dramatic struggle. Or, find yourself an unexpected combination, like the culinarily gifted rat in Ratatouille, or two cowboys in love in Brokeback Mountain.” “The important thing about character-driven scripts is that they get read.” For example, just saying the tension between a working-class woman and her sister, a delusional ex-rich neurotic Manhattan socialite (Blue Jasmine), suggests an interesting dynamic that will compel producers to read the script.

2. The inciting incident is the why? “The reason why a character is moved to act or is trying to achieve a certain goal. It’s the first event, a catalyst. The inciting incident will often read grammatically as a when — for example, when a killer shark unleashes chaos on a beach, as in Jaws”.

3. For action, think about goals: what the character wants and how it will be achieved: for example, to seek revenge on her former elite hit squad, in Kill Bill.

4. The antagonistic force can be an event or person that challenges the character to fulfill their goal. “For example, in Jaws, the shark or the greedy town council can both be your antagonistic force. In the dramatic sense, it’s probably the latter, but it depends how you write your logline. The studio would rather hear it’s the shark, but those in script development would prefer the latter. In Titanic, the obvious antagonist is the iceberg, but in reality, it is actually more about social class than a disaster film.”

There are two other “supplements” for the logline:

5. the milieu and

6. the conflict.

By Sherad Anthony Sanchez

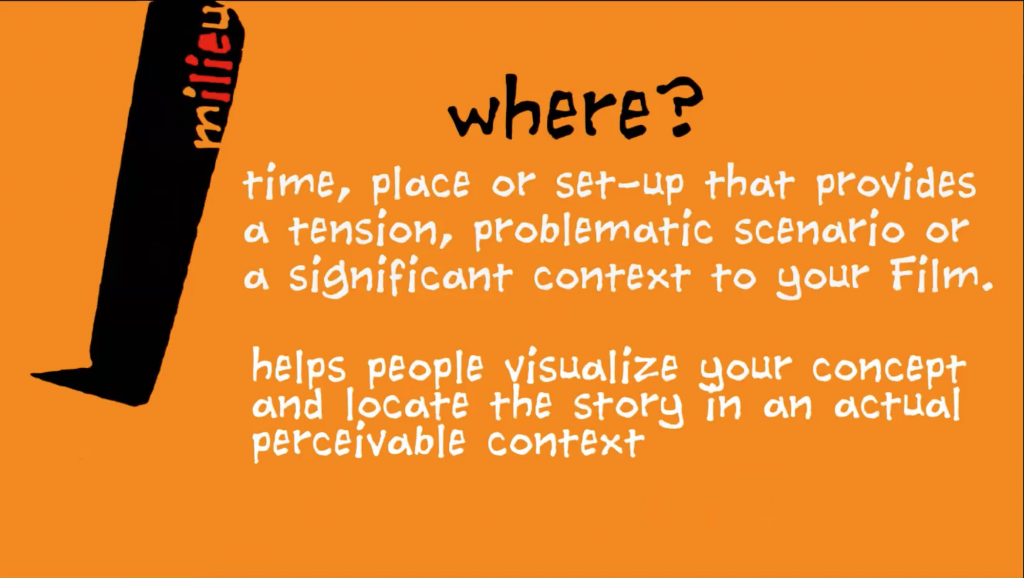

5. The milieu is the “where, the time and the place. It provides a set up and the more it provides tension to your story, the more important it is to state it in your logline”. For example, in a galaxy far, far away. It helps people visualise your concept and locate the story in an actual perceivable context. Or in The Green Book, the milieu of the 1960s American South immediately conveys why an African-American musician’s tour is controversial — due to the ongoing civil rights movement. In the case of a classic story adapted to a new milieu like a musical adaptation of Romeo and Juliet set amongst the gangs of West Side New York (West Side Story), there is no need to elaborate in the logline on the plot.

6. The conflict addresses the which. The antagonistic force usually suggests the conflict, but sometimes it doesn’t. It’s okay to reveal the final conflict or the ending of the story to the producers — though one wouldn’t in the film’s trailer, for example — as the intention is to get it financed.

By Sherad Anthony Sanchez

Note also that a logline is not a tagline, blurb, premise, synopsis or hook. Each of these serve different purposes.

Finding your logline through moment, game, character and milieu

Sherad candidly shared, “When I watch Netflix films, I call them “logline cinema”, it’s clearly a cinema that is developed through loglines. It doesn’t mean that it doesn’t work and it’s not good. It sells. But sometimes, the narrative is not the most interesting way to pitch your film. You might find your logline through moment, game, character and milieu.”

7. “What is a moment? You have moments of conflict, bad moments, poignant moments…a moment can trigger the film. The moment is in the in between. The moment is when there is a circumstance or event that falls on you like an avalanche. The more surprising your reaction is, the more powerful and poignant your moment and the more poetic it can become. It’s not a plot or turning point with a decision to make but actually a reaction to an event that happens, like seeing a dead whale on a beach. And what’s your reaction to make it poignant? That’s a moment.”

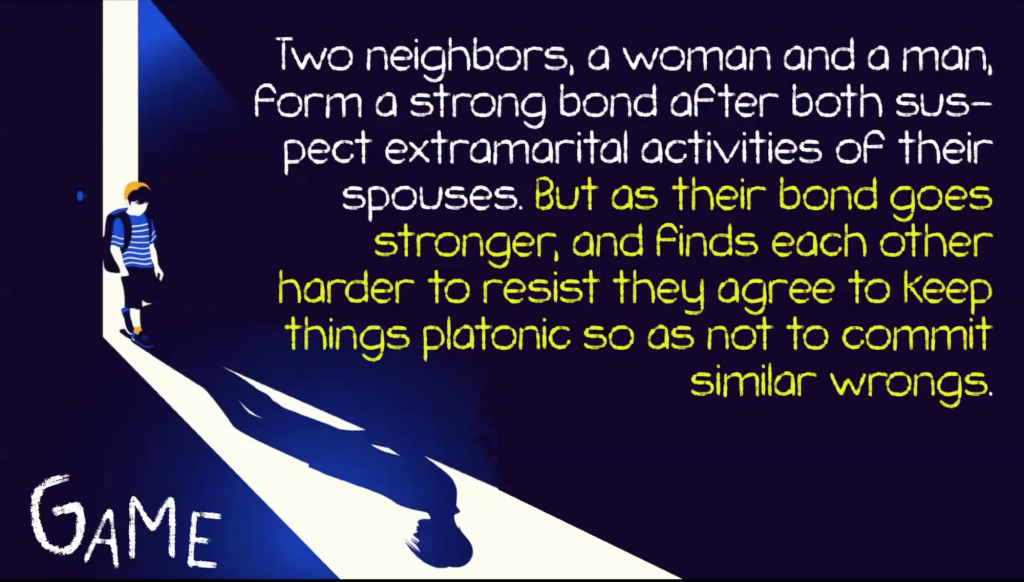

8. The game is “either unique dynamics that the character plays or is forced to play. Or it’s a filmmaker-designed series of events or a designed framing of events. It’s really important for documentary films; as producers we are tired of [pitches] exoticising characters and selling them. If you’ve heard hundreds of these, all the cultural nuances and differences will fade and all that remains is “how are you going to do a documentary about this?”

By Sherad Anthony Sanchez

The game in In the Mood for Love is highlighted in yellow in the slide above — the protagonists are trying not to fall in love or engage sexually. The game is to try to be friends while using their relationship as an investigation of why their spouse has cheated on them.

“However, do not use this approach for convenience’s sake. It would shortchange the pitch for a character-driven film, or a very visual narrative, or one with a powerful conflict or antagonistic force.

Pitching short films, and documentary, experimental, arthouse and high concept feature films

Sherad shared about how pitching for narrative feature films differs from pitching documentary, experimental, arthouse and high concept films, as well as short films.

“Narrative features are a series of moments with a beginning, a middle and an end — and, according to Godard, not necessarily in that order. In film school, you’re usually told that short films are a shorter version of feature films. But short films can be more than that. They can be a series of events leading to just a moment, a buildup of moments, a series of images towards a moment, or a series of images that creates an impression of a moment.”

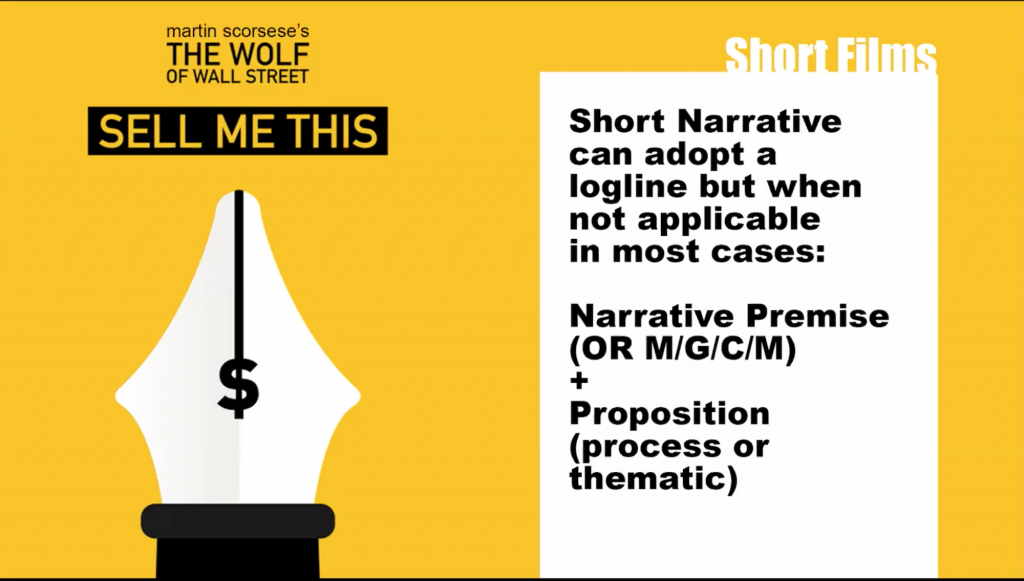

By Sherad Anthony Sanchez

“Short films can adopt a traditional logline, though probably not in most cases. One can use the “moment, game, character and milieu” approach instead.

Another possibility is to share the process or thematic proposition. You can share the story and surprise your producers by saying, for example, “…but it’s all going to be shot upside down” (process). “Remember it’s an art to know when to break the rules. Don’t be afraid to add a personality to your loglines.”

In a pitch, “sometimes the jury or the producer asks for your logline, then a synopsis — but actually they’re one and the same. There is also summit style pitching where you’ve already submitted your logline and then answer questions about your process, plans, treatment, statement. Here, we already know [about the film] so we’re gauging your personality, voice, poetics — the stuff that makes us decide whether to fund you or not.”

“Documentary is an approach or style of filmmaking that concerns itself with representing reality, whether it is framed in a narrative, a game, an experiment or an essay.”

High concept or alternative films often utilise a play of structures, treatment of time, concepts and themes to drive the experience forward. It’s usually framed in a game with little to no regard for beginning, middle and end.

“Experimental is an approach to film that concerns itself in format or process with questions that challenge human experience, the consumption of cinema, or our relationship with cinema. If you are pitching an experimental film, producers really want to know your approach. Make it clear it’s an experimental film so they don’t get surprised.”

In the pitching room

“When I pitch I don’t burden myself with the result, whether my project will be greenlit. When you start thinking that way, you might self-destruct or limit the joy of your project. I care about the moment, to relate to people and build relationships.

Every time I pitch I have a different persona that matches the tone of my film. If it’s a comedy, I’ll be humorous, engaging, funny. I treat the pitch as a performance and not only amuse myself by ‘being somebody else’, but the persona is also a ‘wall’ so I don’t get easily distracted.”

Sherad suggests using slides with few words, and keeping visuals engaging, “Use engaging storytelling to make us feel. Avoid memorisation, just remember your key points. Sound excited, keep the interaction very human-to-human, even if pitching online. Enjoy your story; share it as though you’re sharing it with a friend. Do not simply show us but let us feel your joy for the project.”

“And sleep the night before! Relax. Body language is important; we can feel right away the emotions and authenticity behind your project.”

On whether one can pitch in the same style in different international contexts, Sherad shared, “There is an old myth that you need to cater to who you’re pitching to and adapt your pitch. You don’t want to get the wrong producers and funders to fund your film; for a good partnership, you need to be authentic and honest.”

“It’s not so much regional differences but that different professionals will hear pitches differently, for example, a studio, academics, mentors. Mentors may want to hear your loglines with mention of conflict so that they can help you refine it, while producers are more relaxed. So long as you can help them visualise what they will see on screen, that’s good.”

On whether Sherad abstains from certain terms or cliches in loglines, like “journey” or “coming of age”, he said: “As long as you have a nice irony it doesn’t really matter. Sometimes I like to use familiar words and suddenly turn them upside down. Sometimes cliches connect us with something familiar and then we can defamiliarise it. If you don’t have an interesting tension, there could be an issue. “Journey to self-discovery” is so common. How on earth do we visualise “self-discovery”? Help us visualise it and don’t just rely on the abstract word “journey”.”

On pitch videos

On tips for making pitch videos, as this format became more common during the Covid-19 pandemic: “I use the opening credits to inform the audience who I am, and the end credits to show my casting and my crew. In between, I take them on a journey with images and a few words, to make them feel what the film is all about, and the treatment and style so I didn’t have to explain my vision as director.”

“When choosing visuals for a pitch video, choose what is close to the visual intent of your film rather than its themes. If it’s hard to find suitable images use words sparingly to assist us in experiencing the visuals. I’ve seen two trends in pitch videos: the atmospheric kind which hooks you right away, or a really rapid kind like a music video. When producing, I become cynical of filmmakers’ devices. The faster I can visualise your story without gimmicks and can see how you are being authentic, I’m sold.”

Also read: