Nurul Huda Rashid and Kelly Leow (AWARE) in conversation

Stories That Matter is an annual documentary programme by Objectifs that looks at critical issues and the possibilities of non-fiction visual storytelling. The theme for 2021 was Mediation/Circulation, which looked at the mediation and circulation of documentary images, in turn posing questions about how they impact our understanding of visual culture as audiences, creators and publishers. As part of the programme, Objectifs presented three public talks with artists, filmmakers, NGO workers and academics.

In Women in Circulation, visual artist and PhD candidate Nurul Huda Rashid and Kelly Leow, Communications Manager at AWARE, spoke with Objectifs’ Programme Director and Stories That Matter co-curator Chelsea Chua about how representations of women and the circulation of such images, particularly documentary images, impact on gender relations and ideas about women.

Women in Circulation: Gender in Singapore Advertising

Last year, AWARE published a report based on their content analysis (with advertising consultancy R3 Worldwide) of 200 television ads spanning a range of industries, produced by Singapore’s top 100 advertisers and broadcast locally between 2018 and 2020, with a view to looking at gender equality in advertising.

According to Kelly, ads, “as much shorter forms of media than film or television, are more reliant in terms of storytelling on cultural stereotypes to get their point across. The tropes and narratives in ads reflect prevailing norms and ideas about gender but through what they normalise and problematise also influence how viewers enact these values in their own lives.”

Unlike some other countries, Singapore does not have advertising standards on gender. The Advertising Standards Authority in the UK, in their report Depictions, Perceptions and Harm (2017) which AWARE referred to in their research, identified six categories of gender stereotypes: roles, characteristics, mocking people for not conforming to stereotype, sexualisation, objectification and body image.

The treatment of gender and the nuanced context in which gender is depicted in ads is important. It is not inappropriate to show a woman cleaning but to depict her as the exclusive cleaner in her family or to depict men shirking cleaning responsibilities reinforces negative stereotypes. One ad in isolation is not necessarily a problem but cumulatively, problematic ads build up a strong message over time.

Among other roles, AWARE’s research looked at depictions of men and women having paid employment in the ads they analysed. Ads were 48% more likely to depict men having paid employment versus women. Ads that showed women working mostly also showed her sacrificing family time, and her physical and psychological well-being, to do that work, while for men their careers are portrayed as the rightful objects of their energies and time and not something they had to choose over other areas of life.

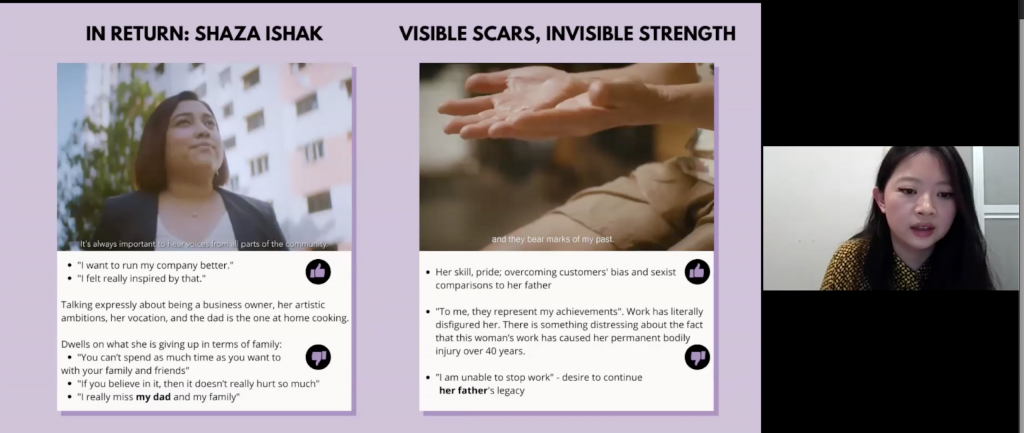

Two of the ads in AWARE’s top ten are:

While both depict women passionate about their vocations, in the first, theatre practitioner Shaza Ishak discusses sacrificing time with family and friends to work while in the second Madam Lee discusses the physical sacrifice and scars she has had to endure in her line of work.

In contrast, in the ads In Return: Interview with Toh Wei Soong, a national swimmer, and In Return: Interview with Kumaran Rasappan, a surgeon and medical volunteer, both men define home as an abstract concept that they can bring with them on their travels, versus Shaza who defines home as Singapore and that her time spent studying overseas entails the sacrifice of being away from home.

In a display of gendered double standards, AWARE also found that conventionally “beautiful” women were coupled with men that were not conventionally attractive. An ad that was highly scored by AWARE from Dove’s Real Beauty campaign depicted a woman living with eczema.

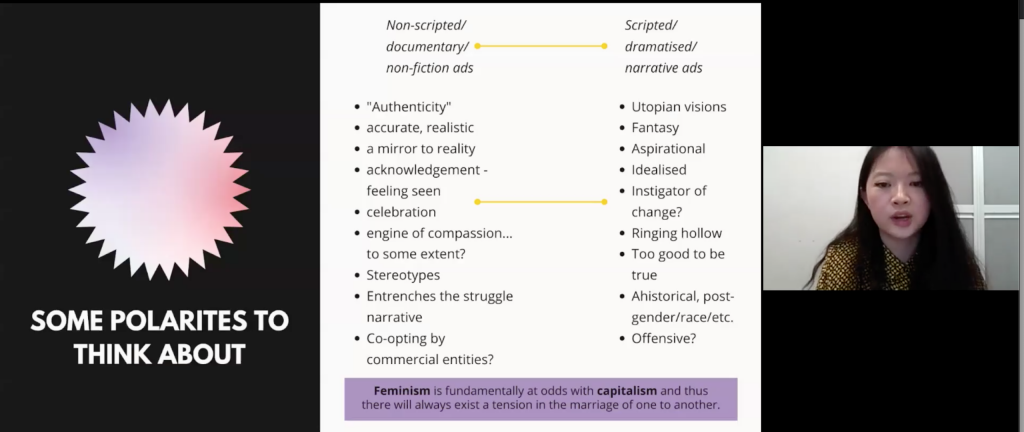

In the context of Stories That Matter’s focus on documentary works, Kelly suggested considering the below dichotomies in relation to more scripted, dramatised ads versus the more “non-scripted” (on the surface of it) interview-type examples she presented. She posed the question: “Is it the goal of ads to reflect reality in full accuracy and authenticity, to allow people who have been previously marginalised to see themselves and feel seen? Or is it to present a more utopian vision of aspirational gender equality?”

“There can be good and bad to both of these. One downside of only ever showing the reality is we end up entrenching narratives of struggle. But presenting the aspirational, utopian vision may also ring a little hollow, ahistorical or offensive, like we’re denying or wallpapering over the truth of what it’s like to be a woman in the world.”

“In many ways the values of feminism are fundamentally at odds with capitalism and commerce. There will always be the tension of progressive feminism and its language being co-opted and exploited by commercial companies.”

Discussing the role advocacy work can play in terms of seeking more equitable gender representation, Kelly shared that while we “think of policy as the quickest and most blunt way to impose a certain value and approach to an issue, but it has to go hand in hand with cultural shifts. That’s where the media comes in.” Using employment as an example, she highlighted that women across industries face maternity discrimination and workplace harassment as early as the hiring process. Such ideas about a woman’s role are perpetuated through various channels including the media. “Even as we’re pushing for anti-discrimination legislation for workplaces in Singapore, we also recognise that it’s not just about the law, but about people’s mindsets.”

Women in Circulation: Searching for Images of Muslim Women

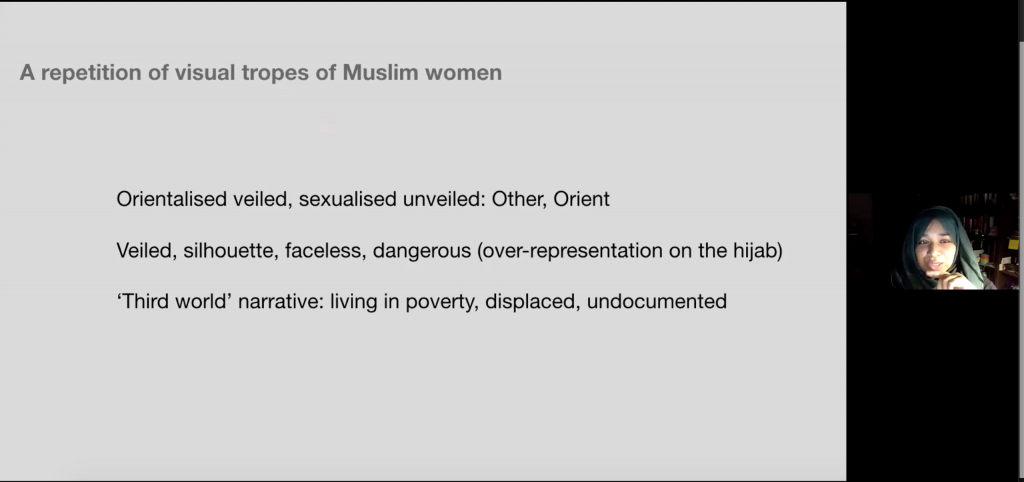

Nurul Huda Rashid’s PhD research examines how images are being circulated through internet algorithms. She is a Muslim woman herself and is aware that the identity of Muslim women has become highly contested and is shaped by the problems that come with primarily representing them as veiled. Building on Kelly’s presentation, Nurul added: “When we talk about representation now, it’s no longer just about what images represent but about systems: about how images circulate through different platforms”.

In hindsight, Nurul critiques her project Hijab/Her (2012) in which she interviewed women who wear the hijab about the challenges they experienced in daily life, and then visualised a series of photographic portraits. She shared: “With the use of the veil as a sole visual, I was essentially reifying the narrative that Muslim women are faceless and that by the sheer fact of wearing a veil they experience hardship. This presents Islam as the problem.”

The image of the veiled silhouette is not a new phenomenon. In early 1890s during the French colonisation of Algeria, the fully-veiled presence of Algerian women was incongruent with the colonisers’ orientalist notions of the exotic orient. In order to affirm their orientalist gaze through the photographic image, the French orientalists staged images of Algerian women as the archetype of the odalisque, or harem women: to be displayed as unveiled, eroticised, and suiting their imagined visual of the ‘Arab woman’.

This was critiqued by Malek Alloula in his book The Colonial Harem.

The representation of Muslim women has also been traced in relation to a kind of “third world” (a term which Nurul acknowledges as problematic) narrative, presenting them as poor, desolate and experiencing great suffering.

Nurul said: “The role of the visual as a starting point has become a problem for me and is why I stopped taking photos in my discussion of Muslim women. The act of taking photos or even finding a way to photograph Muslim women would need me to break away from any of this. At this point of time, I do not know how to do it.”

She shifted from just looking at the role of images in representation to examining systems, the platforms where images are found and circulated. “The images that are revealed through a Google search reveal how the visual tropes we see are circulated now not just in the news, advertising and arts spaces but are made accessible to a larger audience — and in this digital age we’re no longer just looking at something on a screen but as users contribute through activities like tagging to what we all see. It’s not just about what kinds of images we are looking at but how they are organised and circulated in the repository of the digital.”

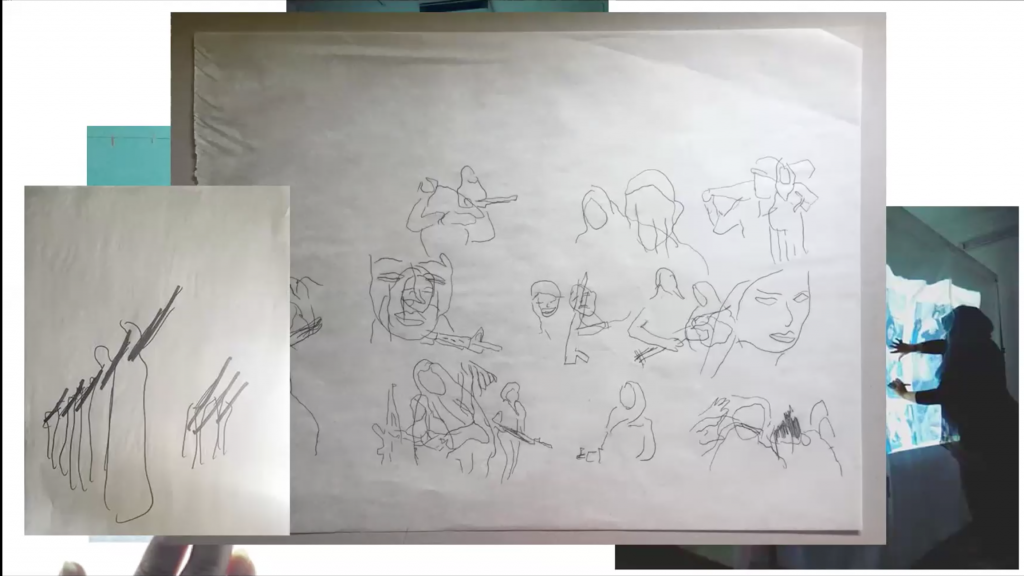

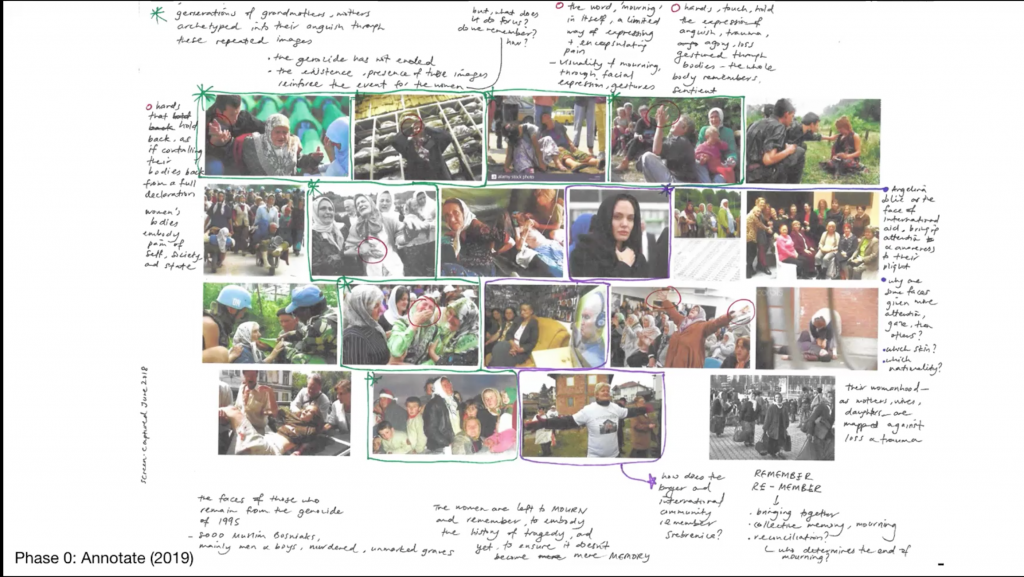

Women in War is Nurul’s ongoing project looking at women as the subject of focus in war photographs. She uses annotations and text to identify repeated kinds of gestures from Google image searches. Gestures of mourning and agony abound, leading Nurul to consider that “documentary photographers look for a certain setting or emotion that would perpetuate or depict the situation they want to talk about. The narrative of Muslim women in the post 9/11 world is that they are in a state of insecurity, are being subjected to torture by the patriarchy.”

“This is problematic because it does not show us any alternative perspective, or does not show us any other kinds of stories, but also because it can even have implications as far-reaching as policy. The algorithm is alive through machine learning and can be biased; it feeds off text and images that we feed into it. As more photojournalists, documentary and war photographers replicate certain kinds of photos, that becomes the bank of images the algorithm taps upon.When we talk about identities and representation it is not just about what the image is about but what the collective image that makes up the larger narrative is.”

Phase 3: Performative of Women in War saw Nurul, through a 30-minute performance, “engage directly with the images. With Google we have the safety of the screen, thinking we are just reacting as a passive audience but in the digital world we also become complicit in how we regenerate, recirculate, how we share, what we share. The act of tracing became an important action to draw a certain kind of resonance with the image. It became a way of trying to meditate upon how you bring a certain kind of affinity or connection to the images you see on screen.”

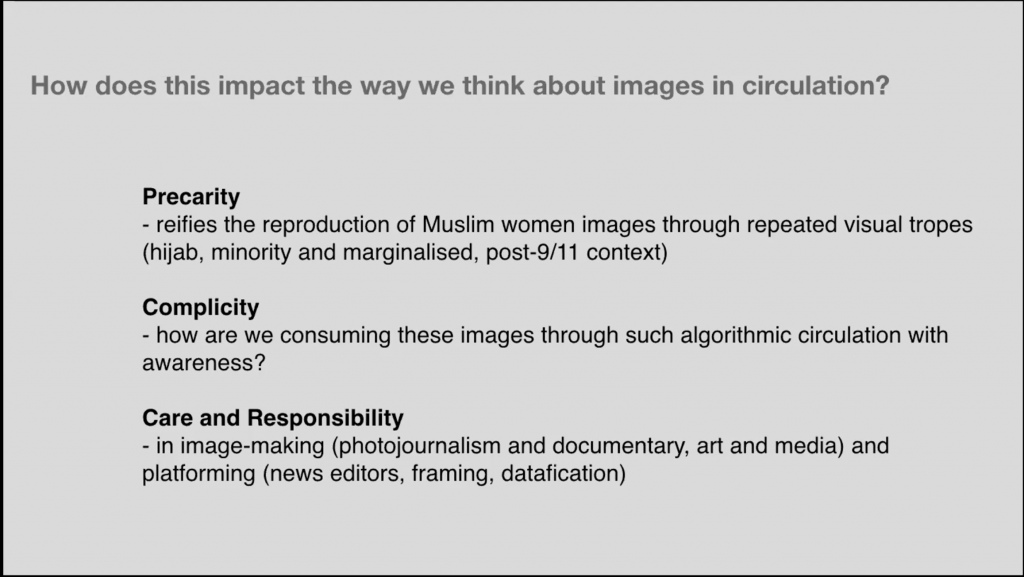

It can be triggering to engage intimately with the images in this way but Nurul believes in its importance “as someone who is going to be doing this in my PhD for the next two or three years. I think it’s necessary to be aware of the complicity I have with the work.” She identified three important anchor points to consider when we think about images in circulation:

Precarity has become an important buzzword but stills holds a lot of ground. How can we stop repeating certain kinds of images and narratives? When the communities we are engaging with are in precarious states, how do we use their image to discuss the issues we want to talk about?

Complicity entails questioning how we are consuming images through algorithmic circulation, and calls us to rethink awareness: if our intention is to use images to bring about awareness, is that sufficient reason to legitimise our act of photographing?

Care and responsibility requires us to consider how we can do image-making work in documentary, journalism, advertising and art. What are we platforming? Where are we putting these images and how are they being circulated? To what extent do we actually have control over how these images are used?

The session’s moderator Chelsea Chua noted that documentary is considered an “arbiter of truth” but that Kelly and Nurul’s presentations revealed the ways in which documentary and our consumption of it is very heavily mediated and reinforced through overarching structures such as corporate agendas in advertisements or algorithms in the case of Nurul’s research.

In response to an audience member’s question on searching for the term “Muslim women” online, Nurul acknowledged there is “already the assumption of a kind of collective identity” and that this has historically been the case as well, where certain nationalities and ethnicities are conflated with Muslim identity. Within social media movements, the hashtag #muslimwomen has a huge following. “For Muslim women on social media who are posting on fashion, on entrepreneurship, talking about the veil, using this hashtag shows a kind of affinity or collectivity” they desire. “Similar to how we we are very critical of the term ‘feminist’ and critical of how feminism should take an intersectional perspective, the term ‘Muslim women’ should also be questioned. Visually, the main problem for me is the over-focus on the veil being ascribed to the idea of being a Muslim woman. We are already affecting the searchability of the term “Muslim women”. We need to address this if we want to talk about intersectional perspectives.”

Another audience member asked about photographs of Muslim women in private settings after they have removed their veils, and Nurul responded that “it becomes a question of positionality”. There are many initiatives (she cited Beyond the Hijab in Singapore) that present the plurality of Muslim women’s stories. Nurul questioned the ability to even capture in a photograph the act of a hijabi woman unveiling as it is antithetical to the choice of wearing a hijab. Algorithms are responsible for presenting us images of women in war when we simply search for “Muslim women”; nowadays we also get many images from the fashion world.

Nurul reiterated: ““The question for me is not what I can do to subvert this but to identify how systems operate and what stories they are choosing. I could do another project claiming what else Muslim are, but it becomes a bit of a knee-jerk response often resulting in minority and marginalised people constantly having to excavate their own stories. Minority and marginalised people constantly have to excavate their own stories. These stories are not random but fed through media and image-makers and continue to perpetuate certain images of Muslim women. It becomes a feedback loop, and about complicity. Are we seeking out stories beyond what is presented by the algorithm? We put the labour on Muslim women but these other stories are indeed already out there.”

Chelsea also noted that the role of the media in establishing and reinforcing stereotypes or tropes may be intensified in the current context of the Covid-19 pandemic where we are connecting with each other through our screens more than ever. While the conversation was in relation to women, Chelsea noted that many points discussed could be applied to other marginalised or underrepresented communities as well. The session ended with vital questions for all of us to consider as image makers in our own right these days, with our camera phones and social media: “How do we introduce more diversity in representation and become more inclusive and mindful in the way we make and share images? When we put images out there, what sorts of tropes are we generating?”