In conversation with Kokila Annamalai and Emmeline Yong

As we strive to tell stories that matter, what are our responsibilities as art makers, curators and community builders in framing or sharing narratives of marginalised communities? This conversation comes as a lead up to our upcoming Stories That Matter 2021 workshop (25 and 27 March 2021), where we hope to bring together documentary photography producers in the field of the arts, media and non-profits to collectively think about the making and use of documentary photography.

Kokila Annamalai is a writer, researcher, facilitator, community builder and arts practitioner. She spoke with Objectifs Co-founder & Director, Emmeline Yong, in Aug 2020, and shared her thoughts about how we can reimagine communicative equalities, our approaches, representations and re-presentations. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Emmeline: What are your thoughts on good starting points for an image maker* who wants to develop work around marginalised communities, or the issues faced by these communities? (*We use image maker and artist interchangeably during this discussion, in reference to photographers, filmmakers or artists working in photography or film)

Kokila: There are several things that come to mind. The first is to have an intimate and empathetic understanding of not just the struggles, but also the strengths, wisdom, and fullness of lives lived on the margins. This is important for any artist, whether they’re an image maker or otherwise.

Another valuable thing to consider is their process, if it is a process of co-creation or of enabling the creation of works by the community themselves, and whether there is space for that in their practice and process.

It’s also helpful to think about what themes to cover, what perspective, what story you’re telling. Who do these narrative threaten? Who do they comfort? What are the narratives or representations that the community seeks to forward, and how does your work speak to that?

On questions of sensationalising or aestheticising issues like poverty, suffering or pain, it’s helpful to ask – do the images we create undermine or honour the agentic capabilities of already marginalised communities or individuals? Do they show them as people with agency, dignity, power, and ideas, doing things in and about the world and their lives, or as passive subjects, who are there to be gazed upon?

There have been particular ways of representing marginalised communities around the world, including in Singapore. Unfortunately some representations either romanticise – relying on narratives of resilience and extraordinary strength – or they undermine their dignity and agency, reinforcing their marginal positions in society. But visual storytelling can be a powerful tool to disrupt dominant, harmful narratives.

E: These questions should be asked through the whole process of the art making. I would add too, that it is important for the image maker to research and understand what has already been said in public discourse, in the popular culture, arts, news, academic writings, etc. What does he or she add to this dialogue, where is this dialogue being situated?

K: Exactly. How will this narrative be received, or situated within the moment, within public discourse. The prevailing narratives, and how your work speaks into that space.

Many of us think that we’re creating work that will speak to a universal audience / “general public”. But perhaps due to our positionalities and unconscious biases, we also inevitably and implicitly create work for particular audiences that might even exclude the very people we are telling stories about. For example, if a work about migrant workers is only available in English, who can access it, and who can’t? We need to ask ourselves these questions, not just at the point of production, but also in the final way the work will be seen and be received. It has to be a self-reflexive process, and we need to interrogate:

Why do you want to tell the story? Who is it for? Does it speak on behalf of or does it speak in solidarity with? What other possible reactions, consequences and conversations can happen as a result of these images? Who will engage with those responses? Is it the image maker or is it the community? Can that be anticipated, and to what extent? Can the communities be prepared for such a conversation that will follow, and can they be in a position to speak into that conversation rather than just be spoken about?

E: Tara Pixley from the Authority Collective said (she raised this as a discussion on photographing protests): “For so long photojournalists have emphasized their intent as if that’s all that matters. The actual impact of our photographs is all that remains once the photos are out there in the world, for better or for worse. We owe it to ourselves, our profession and our public to critically consider the potential impact our photos might have well beyond our original intentions.”

We sometimes encounter artists, who want to create work surrounding marginalised communities, and they distinguish between wanting to retain the integrity of their “artistic intent” and not wanting their work to become “political” or “turned into a community arts/advocacy project”. How does one balance this artist intent versus the care for community?

K: Perhaps we should also clarify this “intent” in the first place. Where does the intent come from? Why do we have this intent? These are central questions in our exploration of an artistic idea, because our ideas don’t emerge from a vacuum that is apolitical. All work is political, so there’s no running away from that. The question then is to what extent we choose to take responsibility for the politics of the work, to understand our own affinities, and how we can care for those we work with, especially when we are borrowing from their lives to create our work.

We can also reframe the way we ask questions about the art-making approach. Balancing the artistic intent with care for the community makes it sound like these are competing instincts or agendas for the artists that they then have to balance. I feel it is possible – maybe even necessary – for artistic intent to include care for people.

E: You’re right that artists can address such sensitivities in ways that do not treat intent and care as competing impulses. An example of such a work is Postcards from Singapore by Lac Hoang, who was an artist-in-residence with Objectifs. Her project is about foreign domestic workers, whose daily movement and rest time are dictated by their employers, and their relationship with public spaces in Singapore. Lac let the women tell their stories in their own voices to address issues faced by the community, while keeping her artistic voice.

K: Yes. I feel they should be mutually reinforcing of each other. What is a good artistic vision, that is not caring for the community?

I can’t imagine how deep care for a community can produce work that is not moving or fulfilling. If you do commit authentically to both your craft and the communities you work with, as an artist, this only improves the work you produce. They don’t have to be compromises or trade-offs.

I can see how it might feel like a conflict, because artistic expression is often seen as a highly individual and personal process of self-expression. But when one chooses to represent others – especially vulnerable groups – the ethics of care should be integral to the process of creation.

E: How can artists check their blind spots on artistic intent, to ensure the intent doesn’t become exploitative or predatory of the marginalised communities they seek to represent?

K: I think that to be a thoughtful person in this world – not just as an artist – is to agonise, to some extent. If there isn’t enough self-enquiry, there’s too much confidence in one’s process, and that is how hurtful or damaging work may get produced.

Checking blind spots should be a constant process in art making.

It helps to have a realistic or grounded sense of one’s value as an artist, because sometimes, there is this sense that artists enjoy special freedoms. While our freedom of expression should be defended in response to systemic or structural repression, we shouldn’t hide behind freedom of expression in response to concerns about our work harming marginalised communities, because freedoms without responsibility are meaningless.

Sometimes, I find that artists respond similarly to state censorship and critique from communities who take issue with certain representations – in both cases, describing the response as censorship and defending their freedom of expression. But the power dynamics in both these scenarios is not the same. To ask artists to be accountable is not to censor them.

E: You spoke earlier about working alongside people rather than on behalf of them. What are the considerations and steps an image maker can make in ensuring that she gives a voice and measure of control to her subject?

K: An artist does not have to be limited to working with communities or NGOs only when she has a long, rooted relationship with them. But it is important that the work is created in dialogue. There needs to be an iterative process, an on-going conversation to understand how that community feels about the images that are being produced. The people who are participating should feel that they have power in the relationship too, and are not just passive subjects. They should get to see how the artist is representing them, have the opportunity to express any discomfort, and have the chance to ask for changes.

It’s important for artists to recognise that they enter such relationships already with a certain amount of power. There is a need to disrupt that, and ensure that they are approaching it from a place of friendship and trust, actively drawing attention to the power dynamic and calling it into question. She can bring that up in ways that makes it safer for vulnerable members to voice any disagreements or desires on how they would like to be represented.

E: Speaking to the community that we seek to represent is very important in checking our blind spots. This brings up the issue of consent, and more specifically, informed consent when it comes to working with members of marginalised communities.

K: Consent is especially important when we think about issues like the safety of a community and of its members. When you present images of them, for example, you might get them into trouble with their employers and other agents who have power over them, or compromise their visa status here. How will such images be received in the current climate, and would this make them vulnerable to societal stigma and backlash?

I sometimes hear street photographers say that it’s ok to photograph and share images of members of vulnerable communities to raise awareness of their plight. But some of these images may present them in a way that heightens their precarity. Sometimes, there is no interaction with these subjects, and thus, no explicit consent. Even if they do give consent, some of them don’t have social media accounts. By virtue of that, they can’t understand the reach or the impact. Social media is a difficult world to understand if you’re not part of it – the views and reactions are hard to grasp if you haven’t viscerally experienced them. It’s difficult to understand the possible ramifications just through an artist’s explanation.

If that is the case, we’ll need to ask ourselves: If there’s a certain story that needs to be told, are there ways to choose a different approach or even a different medium, so that you can tell it in a way where there is more control for the person, or that protects their identity? Can the person have control over what images are put out? I think that’s where the artistic process can be imaginative and creative – to subvert norms around representation and ensure that participants are respected as agentic individuals, whose well-being is key through the process.

E: The awareness about consent is so important, because the implications can never be fully conveyed. This is especially so, when images can go on to have other lives from the original intention, in the form of exhibitions, print publications, social media etc.

As artists, curators and publishers, we have a range of tools in our hands to seek different ways of sharing these stories. But there are some dangers too, given that many of us are now self-publishers on our own social media accounts, without the opportunity to discuss these sensitivities or check blind spots with an editor. This is especially the case with single images, like news stories or Instagram posts, because the most visual photos – which are not necessarily the most balanced or nuanced – get attention.

K: Yes. I think for me, some of the most jarring and glaring examples of problematic image-making are in news or the mainstream media.

For example, the representation of migrant workers, such as an image that a local media outlet chose to accompany stories about suicide in the migrant worker community. The image chosen was quite graphic. It puts an already vulnerable community in more pain and suffering.

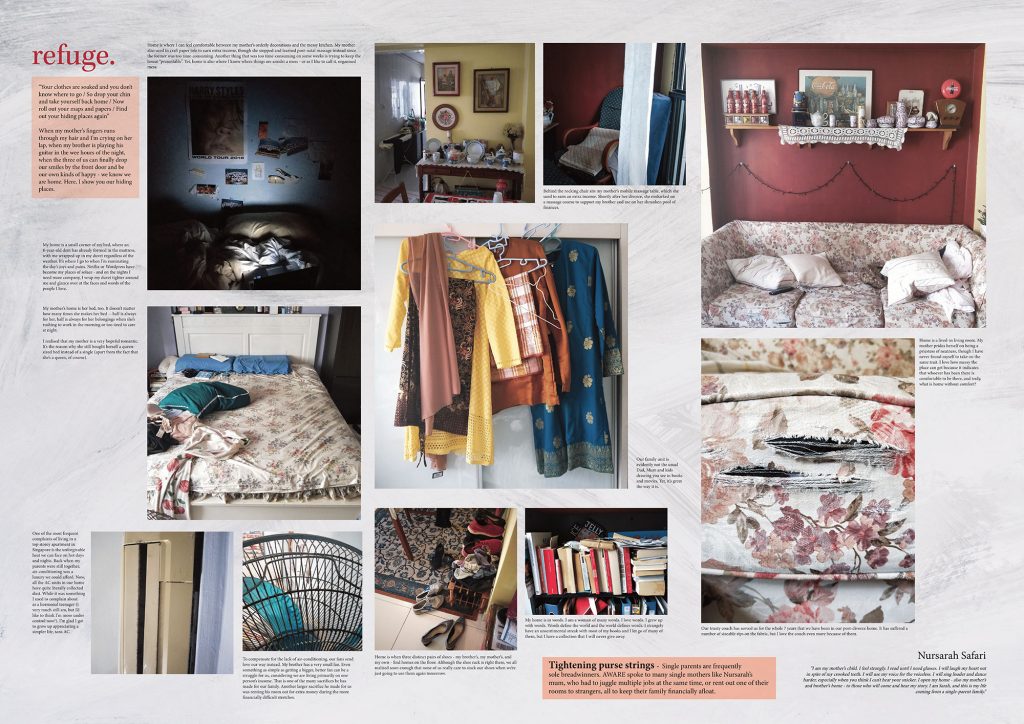

It is hard too, sometimes, for people from low-income families, for example, to work with journalists, filmmakers or photographers. They expect that they will be represented with dignity, and to many, it means they are finally being seen, and so they offer access to their spaces and lives. But the images produced can end up being intrusive and may violate the privacy of these families, even objectify them. Their lives get framed in a way that fits a pre-existing narrative that serves certain political or policy ends.

When the public sees these images they might question: why does this family live in a rental flat and receive financial assistance if they can have a huge TV? The images aren’t able to convey the complexities of living on the margins. For example, that TV is usually the family’s only source of entertainment and it was likely a donation. They can have a TV and still struggle to have three healthy meals. Many families feel dejected and betrayed by these depictions, because the public reaction can get quite ugly. It can even strain their relationships with neighbours and relatives. Because of how poverty is sometimes already framed as a result of poor choices, these images end up reinforcing such public sentiments.

Another example that Project X has brought up is how sex workers are portrayed in the media. Usually they are shown in demeaning ways, long hair hiding their faces, lined up in a row on the street, black rectangles across their eyes, etc. The frame is criminalising and dehumanising. Project X did a photo series that showed other folks represented this way, and I thought this was a powerful way to invert the gaze and call these images into question.

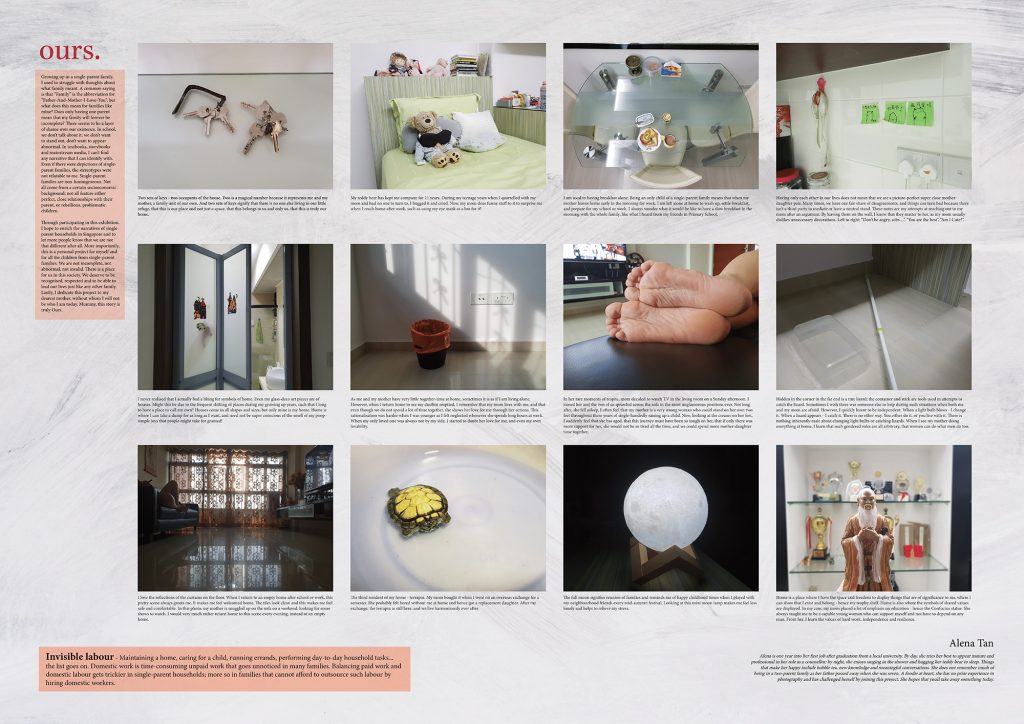

Writer-artist Diana Rahim and Nuraliah Norasid did a photo series to point out the challenges of children from lower income families in trying to find their own spaces to study. Since children are particularly vulnerable, they chose not to include them, and only photographed the areas where they studied. So much was revealed just by the study table (or lack thereof) and surrounding spaces. Their circumstances were portrayed meaningfully and respectfully, in a way that protected their identities but revealed their realities.

I’d like to see more photographers work in these ways when they are exploring issues surrounding a vulnerable community, rather than the traditional “human story”. Can we use other tools of understanding, and gain insight into social realities through other means? Are there ways image-makers can explore important issues without expecting vulnerable communities to expose their lives and subject themselves to further interrogation?

Serangoon North Ave 1, 4-room HDB flat, Bedroom IKEA bed tray

The cosy flat is home to the close-knit family of 3 girls, their parents, their brother-in-law and a highly excitable ragdoll cat named Bulan. The oldest and youngest daughter share a bedroom, which is far too small to fit a proper study desk. As such both would do their work on the bed which they find bad for the back.

The bed pictured belongs to the youngest, who is currently pursuing her degree in Business Management with Communication at a private university.

The middle daughter currently occupies her room with her husband and will be moving out some time next year. On this, the oldest daughter shares that she will be occupying that room and plans to put in a proper desk so that she can better prepare for the classes she teaches at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) and the National University of Singapore (NUS).

Sembawang Way, Void deck common table

A student, who is in her 20s, comes here to complete her school readings when home feels a little too noisy or claustrophobic for reading or studying. She feels that home is often not a conducive place for her as she finds it difficult to get much needed quiet and space as she shares a room with her sister.

She does not have her own desk and shares a cluttered one with her sister. Luckily for her, this void deck table is often unoccupied and though one side of it faces the road, it is relatively quiet and peaceful. There are less of such tables at void decks now, it seems, and she hopes that this one would remain in future days.

E: What you mentioned earlier about the representations you usually get with certain media – the single image or short video often reflects a specific point of view; it’s not a format that lends itself to nuance.

K: Exactly, so there’s already a prefixed narrative of either mould, and then the photo or video journalist goes in search of a community member to fit in. And artists do this too to an extent – they might have stories they believe, which they seek images to forward or strengthen. Not everyone goes to the community with an open mind, willing to be challenged and to learn.

I often find that certain forms of storytelling can flatten lived realities of communities, either through focusing disproportionately on suffering or by romanticising what is beautiful about this community. The ability to recognise and depict complexity and ambiguity makes the story stronger, and more real.

E: What about projects where there are longer-term engagements with members from marginalised communities? Could they lend themselves to more nuanced pieces and reflect the complexities of issues faced, given the intimacy and experiences shared?

I feel that there are certain considerations that are important. For example, when some people’s stories get told prominently, we may repeat these few stories, in ways that end up defining the whole community. When some personalities get featured more conspicuously, such attention may be perceived as inequitable. This can also complicate relationships and cause tension within the communities.

It is artificial, and can be stressful, to live our lives out in front of a camera. So with longer-term projects that involve spending long hours together, I worry if it subjects the individual or community to a performative sort of labour – to perform their pain for us or tell us their stories repeatedly, a mode of being where they can be captured and represented at any point. Does it affect how people see themselves and live their lives? While I do think these projects, if done with sensitivity and authenticity, can be valuable in offering deeper insights, we have to be mindful of the impact it has on communities.

So my question is, would we do that to a more privileged group, say a middle-class family? To spend months on end, sharing intimate aspects of their lives? And if that isn’t OK, why would we subject working-class families to the same? Why do we need to have that level of intrusion to gain empathy or understanding?

Another way to consider this: would I be happy to participate in a project like the one I am proposing? I’m not saying that this has to be the orienting question. But I find it helpful to think about this, if only to understand why, and then to see how to alleviate those aspects of potential discomfort. And sometimes the answer to whether we would participate can be “no”, but it could be important for the community to be represented or participate in such a project, because they can have different interests or outcomes from us.

There needs to be an awareness of boundaries and implications. People allow journalists, artists, academics and others access because of a hope for dignity, attention and a voice. They are trusting you implicitly and are willing to let you into their lives. I think that has to be treated with extreme care.

And sometimes there is the flip side, where we might feel that we need to act as gatekeepers to protect the community. That also has pitfalls, because we are making certain assumptions that can compromise their agency. We impose our concerns on them or prevent them from telling their stories, and that can be a form of censorship. We should instead have discussions with them about the potential consequences, and how can we mitigate them. With longer-term projects, there can be successes, especially when the members can come together to advocate for themselves.

E: The way we think of image making is reflected by our visual references. For example, many local photography students would have been educated on a diet of photos from the West, and often times by male photographers looking at communities with a specific Western or patriarchal gaze and told in a certain formula.

In the last ten to twenty years, we have seen a more concerted shift to reclaim such identities, with institutions and organisations like Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Women Photograph, Market Photo Workshop, Angkor Photo Workshops, that push for stories that are being told within or alongside communities.

K: It goes back to how can we rethink the infrastructure and systems of art making and storytelling. Most often, the strongest stories for me are produced when the art maker is a member of that community or of adjacent communities. Pluralistic lenses, and what anthropologists called “emic” perspectives, are extremely valuable as we grapple with making meaning of and transforming our societies.

As an example, the short film, Salary Day by Ramasamy Madhavan, was made through a collaboration between migrant workers and Singaporeans. It brings across the issues faced by migrant workers in a quiet, powerful manner. There is an incredible difference when it is told, however empathetically, by an artist from outside of that experience versus by someone who resides within that experience.

I have found projects like Photovoice meaningful, as both an emic research process, and a way of deepening critical consciousness within a community. Participants are provided storytelling resources and they choose how to depict their lives. Using the images they create, they have conversations with each other and with groups outside their community that deepen understanding and inspire imagination. For example, children in low income neighbourhoods photographing areas in their neighbourhood that they see as safe or unsafe spaces, and then using these images to work alongside community leaders to make their community safer from a child-centred perspective.

Inclusive art making is an important way to disrupt typical representations. As there tends to be an existing metanarrative in our societies, we usually tell stories within the structure and parameters of that metanarrative, or rigid categories of how we think about people. We tend to think of people largely through a certain set of identity markers. For example, class or race. If we think of people in those categories and tell stories about them only as they pertain to those categories. I worry that stories about marginalised communities end up being told within those parameters only.

For example, if you’re a migrant worker, you are only visible when it’s a story about a migrant worker. If we think about a worker’s lived experiences…could she also be invited to participate in a photo series of parents or artists? This is not to negate her identity as a migrant worker, but to expand it, to make visible that migrant workers are also parents, artists, and so on. Rather than to reinforce existing categories, our storytelling could seek to break them down. If that becomes a part of our praxis, telling inclusive stories will become natural, and expand social imaginaries of identity – who is part of, and who is not part of, a story.

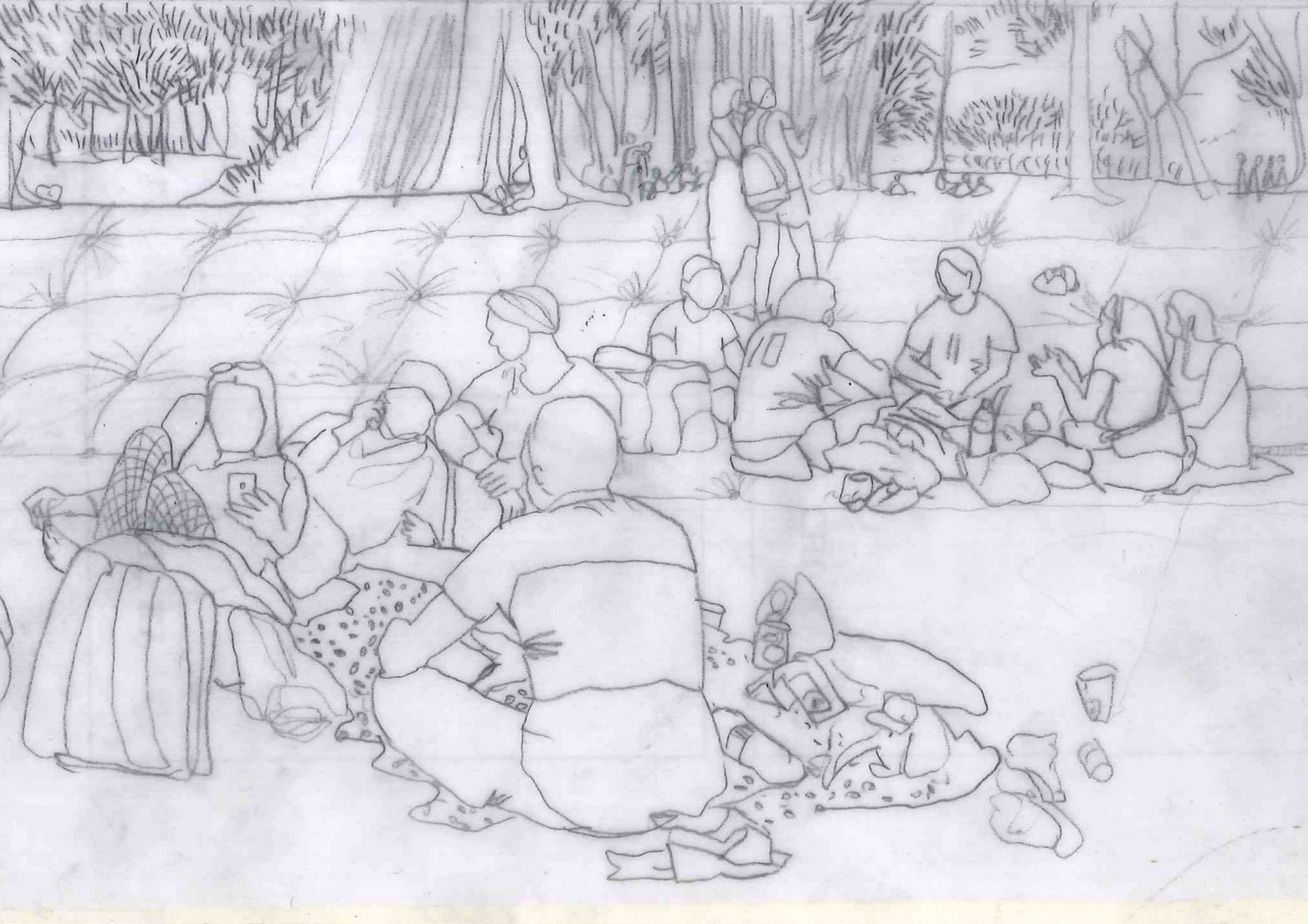

I’ve enjoyed the work of the Migrant Workers Photography Festival. I like some of the work they do because of the space it gives migrant workers to represent their own realities. There was also A Place To Call Home, a photo project and exhibition of single–parent families led by Nurul Huda Rashid and AWARE. I also admire the work of Engage Media, which works with indigenous or marginalised communities, communities in conflict zones etc, to equip them with the technology and image making resources to make and exhibit their work safely.

With these projects, artists and art producers work alongside communities to give them tools, both in terms of physical tools like cameras or video cameras, but also the language of that medium and techniques, so that they can create images that are from their perspective and bring alive the stories they want to tell, in a language that speak to a larger audience.

“In the Bubbles World” by Ana Rohana. Image courtesy of Migrant Workers Photography Festival.

E: What are the responsibilities of curators, editors or publishers? The way images are selected, presented, the accompanying text, dialogue, artist talks etc also shape these narratives. How might we then address issues that resonate or discomfort? How can we make space for the nuances, complexities and tensions to unfold, to ensure that they represent these communities fairly?

K: I think curators need to think about not just presenting work that is about different communities or realities, but also work from artists who themselves are from diverse communities. These artists might not be making work about their own communities, but representing their perspectives are just as important.

I also think curators or editors are guilty of speaking as a final authority on a certain topic. There’s this impulse to present things as complete, as if we’ve thought about everything and thought through everything. But it’s a capitalistic instinct of wanting to present completeness, finished products that are uncomplicated and easily enjoyed or appreciated.

The gaps, conflict, contradictions, errors – these are what present rich possibilities for dialogue. The challenge is to think about ways of sharing and presenting that allow us to be open about the complexities of the issues we’re exploring, our fears and internal conflicts in putting a show or work together, and how they might be unresolved, how our own knowledge is incomplete.

For example, perhaps there were limitations you faced in the research process – maybe you had limited time or encountered your subjects in a context where you could only relate to them in narrow ways. Perhaps you asserted yourself in a way that you later regretted, or you were disappointed that the narratives you uncovered didn’t fit the preconceived notions you had, or were made uncomfortable by some practices of the people you sought to represent, and had to grapple with whether to show some material.

Such curatorial vulnerability and honesty also creates a conducive environment for deep reflection to happen when audiences encounter the artwork.

I think that’s why the arts can be such a profound experience – because you can present alternative value systems, not just work that that speaks to the normative logics of a society. Practicing radical honesty about our subjectivities and power, and the ways in which we are still learning and feeling, can be healing and transformative for communities we are working with, for ourselves, and for audiences.

By not presenting our work neatly, we can force our work to not be consumed, but to be engaged with by audiences. We’re not saying this is beautiful or this is the final word in the matter. We are, in a way, complicating the audience’s experience, creating discomfort, by being radically honest about what is flawed about the project and how it was made, so that they too have to sit with those discomforts and complexities.

E: This brings up the question of the consumption of images, especially in the shifting ways we view images and access art. On social media, we are there for the instant gratification, participating in ways that we dictate, in our own echo chambers and having our perspectives reinforced by algorithms.

How can we equip our audiences with the visual literacy skills that can help them be more discerning, informed, curious, questioning of what is being put in front of them? What are your thoughts on how we can do better as well, in reading pictures, specifically to pictures relating to issues of social justice or vulnerable communities?

K: I would also extend this question: are we consumers of these images or are we the audience? As consumers, there is a certain capitalistic orientation towards the arts, which I think is inevitable because our lives are thoroughly dominated by the market. This has intensified with social media. How we interact with spaces or communities is often construed through a market logic that is transactional or extractive – take quickly, in a way that is gratifying, and then move on once gratified.

As audience members, perhaps we should be more willing to be subjected to interrogation, to sit with something a while, to learn, reflect, dwell on, and honour the generosity of whoever it is that is sharing their story.

It’s also valuable to think about who is the audience, because the work can also be for the members of the communities which are represented in the project. What would it mean for them to view these images? Many writers and art makers fall into the rhythm of telling stories about a “them” to an “us”. Who is the “us” and who is “them”? Can we reimagine who “us” is? I think this is where distribution of images matters, because showing the work on platforms that are accessible to diverse communities and segments of our society is important.

E: These implications, and how images and art can have other impact beyond our original intentions, again remind us of our responsibilities through this whole process of creating, editing, curating and publishing.

K: I think one fundamental responsibility is to relate to people as peers, and not just as passive subjects or beneficiaries. In that way, we understand our role as being in solidarity with them, and start from a place of acknowledging that there is deep injustice in the way that our society is organised.

How can we look to imagemakers and storytellers on the margins, for not just their participation, but also their leadership in the arts? Solidarity is a critical practice because it insists on interdependence, and on caring, reciprocal relationships. It transforms social relationships and how we engage with each other across segments or classes of society, and also how we engage with the state. And so, when we push for progressive and inclusive practices in the arts, we should be informed by the principle of solidarity, rather than of generosity.

And I think the other fundamental responsibility is to commit to a continually deepening practice of inclusive art making. This also means considering questions like, for example, who in your team has caregiving responsibilities, and can your budget for the project you’re working on together include provisions for caregiving? Is your exhibition held in a wheelchair-accessible gallery? Do your images come with image descriptions (as distinct from captions/accompanying prose)? And especially, if you’re creating work about the margins, is it accessible to the margins?

Find out more about our upcoming Stories That Matter 2021 workshop (25 and 27 March 2021) here.

Images included in this article are copyright of the respective artists and organisations.