A public talk by Dennese Victoria for the Shooting Home Youth Awards 2021

The Shooting Home Home Youth Awards, Objectifs’ annual photography mentorship programme for participants aged 15 to 23, included two public talks this year. Read on for a recap of the first of these talks, in which Dennese Victoria shared her tips on starting a personal photography project.

Dennese Victoria (b. 1991) is an artist living in the Philippines, where she works as an educator, cultural worker and cinematographer. Her works, across photography, moving image and installation, touch on truth, memory, personal history, and the exchanges that occur between herself and those that are reached by the forming and sharing of her work.

The conversation has been edited for brevity.

Dennese began her talk by insisting that she is “not necessarily an expert. I feel like I’m always going to be a beginner. It’s okay to be a beginner; it’s okay to be lost. When I need to make something, it always begins with a feeling I have to follow and listen to. Later, my understanding of my own work will change.”

Dennese studied journalism in university in the Philippines, and took an introductory photography class in which she was taught with a mobile phone camera. From 2011 to 2014, she interned and then worked full-time at a television documentary show called Storyline, where “the content covered could go from very personal stories of normal individuals, to people in power”. This was where she acquired her technical training and an introduction to documentary work: “Depending on the person and the story, an interview could be two or three hours long. I would already know the subject’s whole life story before I started shooting them. My task was to draw out every emotion from them: I needed a shot where they were happy, a little contemplative, where they looked in love… Sometimes, people are not in love any more and it’s really easy to see. It could be hard because we needed material as evidence of this love.”

“I didn’t realise how spoiled I was in terms of finding people because I was the videographer. There were three, four of us. There were also researchers, so we weren’t the ones finding the story. Though I’d sit for a long interview, it was actually others who looked for the people I was about to film. I wasn’t always present. I know I did my best but I didn’t realise how generous it was to be let into someone else’s home.

“In retrospect, people are so generous with their stories, as photographers and whoever works with images will realise. Imagine reversing the camera and looking at yourself. How did that person tell their story? How do you negotiate what to share and what not to do? It depends on who’s listening. If I feel like the person is listening, I will be more open to share.”

When Storyline ended due to insufficient funds, its director moved into advertising and took his team with him, which is how Dennese entered this field. Though the work didn’t entail “directly selling something” but using a documentary approach for commercials, Dennese “couldn’t handle the advertising world, though it paid well”. Documentary advertising as well as growing up believing in documentary as truth, but then realising images are not enough to tell the truth of where we’ve been, was “heartbreaking”. She went on to work a government job in the cultural commission of the Philippines, where she learnt a lot about the country.

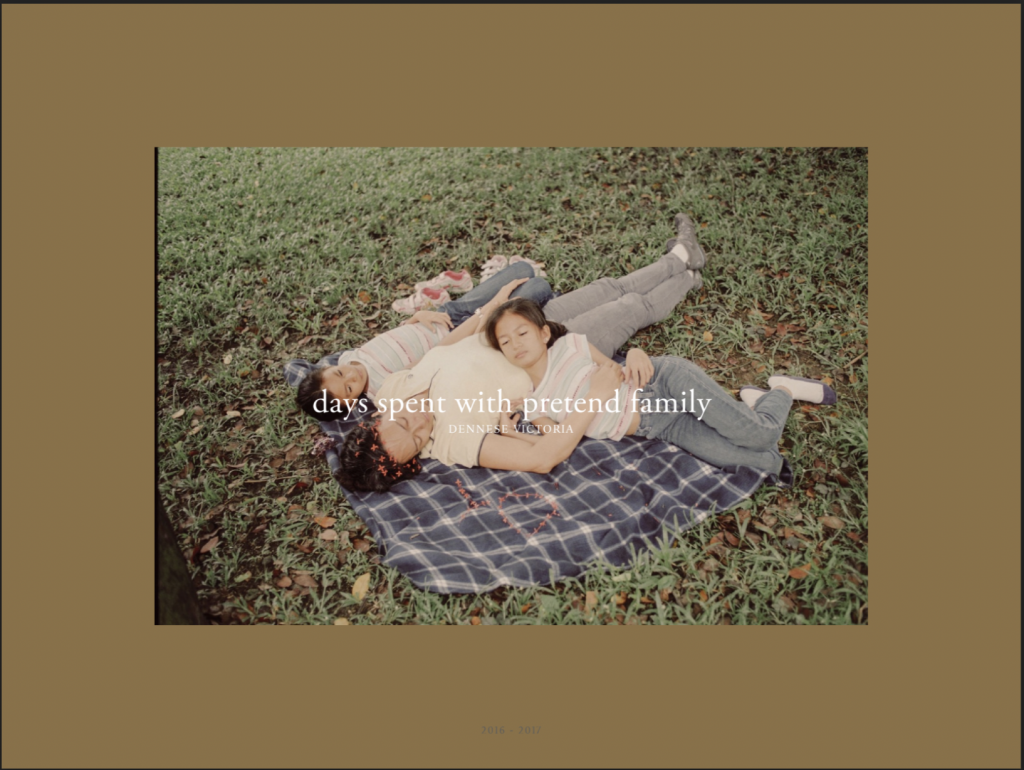

Days Spent with Pretend Family was made for the Southeast Asian Photography Masterclass by OBSCURA Festival of Photography. The workshop was themed “youth and the future”. Back then, Dennese didn’t know how it fulfilled these criteria; she was responding to familial traumas. But looking at it now, she feels it’s about “the childish desire to have some control over time, which you think you can control. I remember being really sad when I made it, but now it feels like when poet Louise Glück said in “October”: “I can finally say / Long ago”. Dennese shared: “I needed to ask myself if I could live with a liar. I realised lying is very expensive. The project cost me a lot.”

In a “period of breakdown” between 2017 and 2019, Dennese questioned herself: “I go regularly into seasons of doubting art and if it matters to be an artist. It’s part of my creative process. When I’m in this season, I go look for a ‘real’ job”. She taught community service at the university then, while “coming to terms with [her] own humanity and being humbled by what being human means”.

At this stage, Dennese “wanted to bring other people into [her] work”, but “could not bring [herself] to say anything, only to open the door”. So, her project for/after, initiated during a self-directed residency at Los Otros, was a simple invitation for strangers to hold hands with her. This exercise was her first time facing childhood trauma and issues related to touch. She “made rules to keep [herself] safe, like ‘no talking’” but of the two respondents to her open call, the first had been through many difficulties, and Dennese “needed to break that rule, to talk afterwards”.

From “for/after” by Dennese Victoria

For her second invitation flowers for while at Los Otros, Dennese “wanted to receive other people’s sorrow”. She reflected that she is “not entirely happy with how [the images] were photographed” but acknowledged that “it’s part of [her] work that [her] visuals will have to catch up with what [she feels]”.

Lim Mingrui, Objectifs’ coordinator for the Shooting Home Youth Awards, described Dennese’s approach to photography as “following your impulse, being true to your impulse to document the process, and making work that can be shared, and inspires others to follow the same process”. Due to working this way, Dennese shared, “The photographs were always just mine. I didn’t need to think about where they’re going to go, and didn’t have to explain them”. Only when she attended the Angkor Photo Festival did she learn that photographs can be exhibited, after which she began to think about “gather[ing] these projects to share”. It is usually invites to group shows that “force [her] to share [her] work”.

Having recently been offered an artist fee —”not a small amount, but like my monthly salary” — for the first time for her own work (not for a commission or collaboration), Dennese has been thinking about compensation and reciprocity in her own engagements with others. For for/after, she was trying to offer coffee in exchange for people’s contributions to the project, but dropped the idea due to complications in arranging deliveries to participants overseas. Dennese reflected: “I was thinking about how honest or sincere that was, if I was again trying to buy people’s time or immediately pay for whatever they were offering me, which I tend to do because I worry that what I have isn’t enough. So I try to overcompensate.”

Dennese shared: “A large part of my work and my life in general is working with what’s given to me, what others give me. Sometimes, I feel like I’m testing people, but in a good way. I like to be surprised and in awe of the person in front of me, and what they’re offering.”

While she is careful about involving others in her work, as evidenced by her establishing rules for her invitation projects, she acknowledges that she wasn’t “completely obedient”, having, for example, made independent decisions in “deciding to project and film parts [she] liked” for an installation of for/after. She shared: “I think this work is about it being okay to really take what you need. I release myself from the burden of having to be the person who is open to everybody.”

But above all, she keeps in mind to cherish process over product: “When I finished the edit for this, I wasn’t really satisfied. But when I heard myself say that word, I thought of how it’s used in advertising. I want to remember how valuable other people’s time and attention is.”

These days, Dennese is “challenging herself to “make work out of other emotions. My brother asked, what if you run out of personal issues? Could work made out of joy be art? Would it be meaningful, and moving?” In response to an audience member’s question about what she has learned, Dennese responded: “I wish I went even slower, like I’m not even in the game. I’m still learning that when I make work, I need to show it.”

In line with her thoughtful and intentional approach to photography, she feels that “even [her] day jobs are part of [her] creative life and work”. She added: “I don’t do it randomly. Working in the government, or teaching in a university, or now in a high school, is all part of it. I’m just looking for where I can be most effective as a person. But I also have a lot of shortcomings. So I’m trying to look for the places and the people with whom those shortcomings will be okay, will even be needed.”

“The purpose of my work is not for people to fall in love with it but to help them find their own. It’s so that they can forget my work and remember that oh, I really want to make something. This girl, her work is so simple. I can do so much better. That would be so nice, to feel that I want to make something out of my life.”

In response to another audience member’s question on how poetry and language enter Dennese’s processes — whether they inform her impulses, or come after, Dennese shared that she “experienced text first, and knew that it was as important [for her] as the image”. For her, such text is “preparation, a journey in the beginning to hold [the work] together”. She also uses writing in an evocative way in her projects – for example, “describing an installation as “sorrow container with household items” gives a different tone than just “mixed media”.”

Referring to her sharing the text accompanying each of her projects during the presentation, she acknowledged: “I’m leaving it here. Some of you will pick it up, and it may be a kind of seed, influencing you slowly. Not all of us are interested in the same information or process it the same way. People can journey with me in layers – if you are like me, we can go further.”

In response to another audience member’s question about what shapes her ways of being sensitive, vulnerable and open to the world, Dennese advised: “Take care of your ability to see. It’s so easy to get lost and be so negative about things about people. As you grow up, it’s actually harder to keep your heart open.”

“Most people are sensitive but have also been broken before. Even now, when I’m happy, it’s harder to bear witness because you feel protective of your happiness or your securities. I’ve been hurt, and scared of being an outcast or unaccepted. I’ve felt like I don’t belong. That’s why I’m careful around people, because I know what it feels like.”

Having “always been in positions where [she had] access to leaders, experts at their jobs”, like PhD holders, Dennese has noticed that “it’s so easy to get bored or not be impressed — they know so much, they are tired; the know the best”. She shared: “I want to remain impressed by other people, see why they’re beautiful, and to remember that I need what they bring to the table. That’s how I knew it was important to take care of my ability to see, because I don’t want to get to the part where I don’t see you clearly.”

Among the habits the advertising industry espouses is “how we can dispose of people… it’s so much easier to move on than to stay, listen and care. New Age stuff tells us to cut off toxic people, but all of us have the capacity to be harmful to others, to not be charming,” Dennese reflected. “I’m trying to navigate that now. There are people who are hurting and you can slow down and not just leave them. Give them a chance.” Mingrui further highlighted the possibility of “taking turns to take the position of care and uplift people around you”, and that the journey towards this possibility is seen in the evolution of Dennese’s work “from initially very introspective, to the more recent invitations for people to offload their care”.

In conclusion, Dennese described her work as “the first attempt to solve a problem”. She elaborated: “I have a love-hate relationship with humanity. Being alive and with people can be beautiful but also hurt so much. When I’m in that place, I make work to get out of it. I want to see properly, I want to wake myself up.”

Observing that many photography works now are “more emotional”, Dennese shared that when she was starting out, she felt guilty for making personal work that is “not about proper issues, real world stuff”. But she “works sometimes with filmmakers who are of a better calibre of responsibility than [her], submitting [herself] to their processes and assisting them” in roles such as cinematography. She cited Hannah Reyes Morales and Veejay Villafranca as photojournalists from the Philippines who make personal choices she trusts in terms of “what they pay attention to in the world”, which frees her to do the work she needs to do.

Dennese concluded by pushing back against notions of scarcity and competition that suggest “there’s no space, there’s so many of us [photographers] in the scene. There is so much work that needs to be done in the world, and a lot of us have to do it. I like that there are others working with me.”

“Hopefully, my sharing frees you to make the work you want to do. I hope people will come and see you, and not the cloak of someone else. They don’t know it yet, but they want to know you.”