Featuring Mysara Aljaru, Yanyun Chen & Sara Chong

As part of Women in Film 2019, Objectifs invited five women artists from Singapore to respond to the theme Remedy for Rage using the short film format. Read on for a recap of the artist talks by participating artists Mysara Aljaru and collaborators Yanyun Chen and Sara Chong, with moderator Leong Puiyee from Objectifs. The other exhibiting artists Kris Ong and Chantal Tan were not present due to conflicting commitments. The discussion has been paraphrased for brevity.

Mysara Aljaru is a documentary producer and writer whose works explore issues of identity and the lives realities of minority Muslim women and non-males. Her short film Suaraku bukan dosamu (My voice is not your sin) is a self-portrait together with the different and shared experiences of other minority women who grew up in Muslim households. Read more about her and her work here.

“Rage is not necessarily a bad thing. I wanted to look beyond it. I’m invested in the politics of space. We cannot talk about feminism without discussing intersectionality. My work looks at the idea of a safe space. The video is just one part of the installation; I would like for it to be seen as a whole. For Malay girls, our bedroom spaces are often policed, so we are always going out to seek spaces elsewhere.

In my film, I spoke with women who grew up in Muslim households and featured two spaces: Penawar (which means “antidote” in Malay), and Beyond the Hijab, an online space which features narratives not seen in the mainstream media. There are stories you won’t get anywhere else, and these are spaces to work through what we have been through.

The scrolls are like curtains and are printed with my own experiences as a Malay woman in Singapore. I also discussed what we see on television, and my conversation with a cab driver, which many have shared they found entertaining. I have also displayed books that influenced me, including works by local writers like Alfian Sa’at and Nuraliah Norasid.

Most importantly, my work is about what it means to be a brown woman. It is not an opportunity for viewers from outside the community to demonise Islam and Muslim men. We don’t get much representation in film, and it’s frustrating as we don’t get our voices heard.

We don’t just face rage, we are also tired. There is the assumption that certain systems that work for certain women work for all women. I’m a feminist but my lived experiences may be different from yours. Women from the majority should step away from speaking for the minority.

Some viewers have shared with me that they find this work “moving” or “touching”. I am not sure how to feel about that. I don’t take it as a bad thing when people don’t know how to respond to it.

“Suaraku bukan dosamu (My voice is not your sin)” by Mysara Aljaru

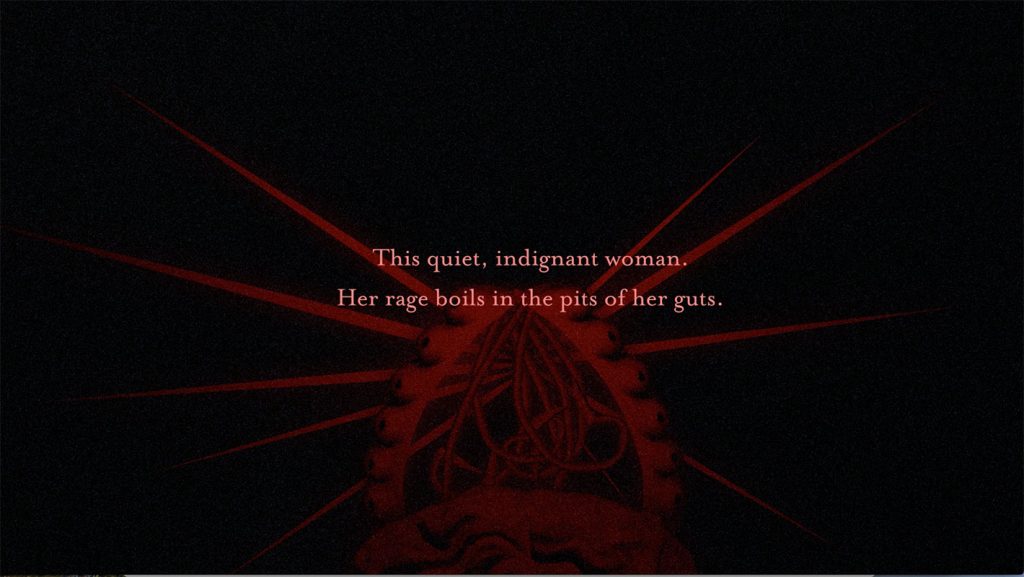

“Women in Rage” by Yanyun Chen & Sara Chong

Yanyun Chen and Sara Chong are artists working in drawing, installation, painting and animation among other mediums. Their collaboration Women in Rage imagined the anger of mythical female monstrosities. Read more about them and their work here.

Yanyun: Rage was the word that called out to me when I was invited to participate in this project. I invited Sara to collaborate with me. I researched mythical female monstrosities and women from various cultures and traditions: Kali, Venus, Rokurokubi, Medusa, Sita, Athena, Phryne, Pontianak, Lilith, Eve, Du Liniang, Izanami and Coatlicue. I saw that many of them were misunderstood in some way.

For example, there is very little mention of how Medusa became so. The Pontianak feels a lot of suffering, sorrow, grief, anger and guilt around a birthing that did not go well. It’s like communities and societies don’t know how to deal with guilt, so we foist them onto these women.

The Rokurokubi is a woman trying to leave a difficult situation. Kali is a mother goddess with an immense sense of responsibility: she is responsible for everything from birthing, nurturing, protecting and destroying everything else that doesn’t fit within the order of things she created. Who decided one woman had to take on all these responsibilities? We see in these myths that women are depicted either as demure and subservient or monstrous, which is very limiting. There is a lot of strength in how they negotiated their situations.

Sara: I like being “ragey” because it’s very cathartic. You can feel empathy for monsters; they’re like people we can’t deal with. My work deals with fragmented bodies, cultural wounds and inherited traumas. Our process for Women in Rage involved taking photos of each others’ bodies and slicing the parts and reassembling them. It was a marriage of 2D drawing by hand, and animation.

Yanyun: The idea of dismembering parts and recreating something else was very empowering, to see body parts moving (animated) that are part of me. It is an act of giving up your body to someone else but because they have the same vision as you, it’s like gifting versus being taken advantage of.

Sara: We thought about art as dismembering what has happened to you and putting it back together, but you also feel a sense of responsibility because it’s not your own body.

Yanyun:

You can tell a story about someone or you can get to know them — the “other” — and then shift the story accordingly; that’s what mythology is. But because only a select few have had the opportunity to do so, they change the stories only in the ways they want to. It’s very easy to create a monster.

Mysara: The Pontianak is not given justice. The language used to describe her is very violent and one of control, like driving a stake through her neck. It’s good to relook narratives we have grown up with. Even remakes of older works about these figures (like films) don’t always get who they are right.

Yanyun: Yes! Why is there always a need to immediately suppress the superpowers or special skills these beings have?

Mysara: There are places where the Pontianak is seen as a guardian or protector, like in parts of Indonesia.

Puiyee: What remedies for rage does each of you continue to practice?

Yanyun: The act of storytelling can be healing. When I can tell a story the way I want to, when the audience is confronted with something jarring or out of the ordinary, it’s like teaching someone the habit of just listening. It requires being present, engaging with the work.

Sara: I try to infuse small things into my day job as a commercial illustrator and content creator. For example, centering women characters in videos, drawing certain figures as more gender ambiguous.

Mysara: I seek to break narratives we have internalised, inherited or been exposed to and doing so critically, without tokenism and taking an intersectional approach.

Women in Film & Photography: Remedy for Rage’s ongoing exhibition and short film installation continues at Objectifs till 17 Nov. (Open Tues to Sat, 12pm to 7pm and Sun, 12pm to 4pm)