Filmmaker Gladys Ng & photographer Ng Hui Hsien in conversation

Our fourth Objectifs Film Club session, held online in July 2020, featured filmmaker Gladys Ng and photographer Ng Hui Hsien in conversation about their respective works: short film Still is Time and Myth.

Read on for a recap of their conversation, in which they discussed how intuition, play, spirituality, ambiguity, observation and contemplation figure into their respective practices, and more.

The conversation has been slightly paraphrased for brevity. Please note also that it contains slight plot spoilers for the short film Still is Time.

Puiyee (Senior Manager, Objectifs): We thought it’d be interesting to have this conversation with Gladys and Hui Hsien as both of them make observations about human emotions and their nuances through their work. I’d like to start off by asking Gladys, how did the idea for Still is Time begin?

Gladys: Still is Time was created as part of a series of six short films that was called Void Deck. Each film was supposed to be set in a specific neighbourhood or estate. For Still is Time, we chose to set it in Potong Pasir because I live near that area. and take the bus and pass by it almost daily. I was very curious about this little estate that was surrounded by greenery. When this opportunity came, I thought it was a good time for me to explore the place, and to understand it better. This film follows a father’s journey. When I created the script, it was really a very intuitive process. This script, as compared to my previous films, had the least number of drafts.

Hui Hsien: You’ve mentioned before that you walk a lot to look at locations. How do you decide on where to shoot?

From Still is Time. Film still by Amandi Wong

Gladys: When I was in the pre-production stage, my DP [Director of Photography] Kang Wei and I would go to Potong Pasir every week to look for the right location. I guess the right location to me was a space that had a lot of different textures.

If you look at this picture (above), where the Dad would eventually turn into a table, what I really liked about the place was the chain. The chain was just rusting, and part of it stained the wall. It makes you wonder what kind of history has passed. You get a sense of how you can tell it’s been there for a long time, but you don’t know exactly how long. I think it suited the film really well. There were some chairs as well, which were not included in the film. The chairs were chained to the pipes. It felt to me like there was a strong sense of attachment, of refusing to let go.

When we came across this location, we were so in love with it. So we thought, OK, we have to set this film here. As much as possible for the film, we wanted to keep things very natural and use what the place had to offer us, rather than try to construct a lot of things. But for this particular shot, we added a few more plants just to make it a bit more interesting.

Hui Hsien: It sounds like the way you choose locations is also about intuition. And you had mentioned that writing this script was one of your most intuitive ones. Can you share how intuition comes into your work process? When do you put it aside and how do you strike a balance?

Gladys: Actually, I tend to plan a lot, since I don’t want things to go wrong. But at the same time, that’s not very intuitive. So balance is the right word — how do you find this balance? Having something very structured versus what you feel is right. I guess for me, intuition comes when you respond to challenges and changes.

For example, in Still is Time, there is the scene where the Dad walks home after buying bread. He walks home, and looks up at the tree. He looks back down and you see the little girl. That scene was not in the script. It was another scene altogether. But when we went to the location, we felt like the original scene that was written couldn’t work in that space. One of the days when I was walking around Potong Pasir by myself, that scene just came to my head, and sort of appeared. I didn’t know what to do about it, but it didn’t really make sense to me. But it felt right, it felt like it had to be seen. And so we decided to put it in.

So I guess it’s this balance of things feeling right and going with how it feels. I trust the intuition of the people around me as well. So when collaborators say something’s off or if they see certain things, even without having a very clear explanation, sometimes I would take the time to think about it.

What about you? Tell me more about how you work… how does intuition come in?

From Myth by Ng Hui Hsien

Hui Hsien: I work more intuitively. I don’t really set out with a fixed plan, like some artists who do work with a concept in mind and then they go out and implement it. I work a lot with my own emotions, like how I feel in a particular place.

Myth is a series of prints made without a camera in the darkroom. It started when I was just walking around in Bristol, England, in a place that was near the countryside. I was walking quite a bit in nature, and I found myself collecting flowers, leaves, tree bark…and it was not really rational, but more of an intuition. I began to take them into the darkroom to experiment, and there was a lot of trial and error.

But after some time, I realised that the process could be used to create images that reference the natural world or the cosmological, and that I was quite fascinated by how these mundane bits of nature could be used to reference that vast expanse of space or nature. The work has been presented in different ways, in my grad show and also during a residency which was funded by Grey Projects and AIAV in Akiyoshidai.

Gladys: So the things that you found, and shot eventually…did you have an idea of what you might end up with or was it a process of exploration?

Hui Hsien: Well, there was no camera, so there was no shooting. There’s no photographing. But it was a lot of manipulating, like touching and experimenting with the materials in the darkroom, trying out different results with the chemicals.

I didn’t start out with an idea of what I wanted. It was really about learning about the materials, finding out what they could be, making these photograms by exposing them to light in the darkroom, and then just going along in that direction. And I kept experimenting, for example, sometimes I would use a torch light or the enlarger light. It was a lot of playing… it wasn’t planned. A lot of spontaneity…responding to my emotions and seeing what else there was.

Gladys: Yes, I think play is so important. Do you feel like you approach your work with a sense of play?

Hui Hsien: Yes. I think

when I’m ready to show my work, it’s professional and serious. But in the making, play is important. That’s a space of freedom for me.

It it the same for you?

Gladys: Yes.. With Still is Time especially. There are reasons why the Dad transforms into a table in the film, but I was also trying to explore playing with a sense of reality…how the film starts off as one thing, and then slowly starts becoming a bit stranger, and stranger, and then it kind of evolves. I was trying to play with the technique first of all, and then I started playing with expectations and reality.

Puiyee: For Still is Time, you had also wanted to focus on the father losing the center of his world [on the day of his daughter’s wedding]. Could you share a bit more about that?

Gladys: When I wrote the script, I took a personal approach. But because this film was commissioned by StarHub and meant to be online, there were many agencies involved along the way. So when I submitted a script, there was a strange air of suspicion. I had to explain many things. For example, why is your film set in Potong Pasir? Secondly, why does the Dad turn into a table?

So for me what the transformation represents is: on this very day, the Dad is about to lose everything that he finds comfort in…his stability and everything is taken away from him. It feels like he’s losing the center of his world. Those feelings sort of manifest within him, and they take an outward sort of effect. And so he starts to transform into a table. That’s what the table represents. But it can mean anything to anybody, and you can read it in any way that is based on your understanding on the location, or end of life in general.

Just to share a fun fact: the table at the start, where the bridesmaids are gathering. That is the table that the Dad turns into. I didn’t want to focus too much on that, so we didn’t have a close up shot to drive home that point. But I think it would be something that perhaps one might notice if you watch my film a second time.

Hui Hsien: You’ve talked about the table as a metaphor for the father, but when I watched the film, I also noted these beautiful shots of trash, of a discarded pillow, bolster and things like that. Could you elaborate on that?

Gladys: Those images can serve different functions if you read them differently. In the context of the film, when you already know the story and you’re following it, it feels as though that those items are similar to that. That makes you wonder what kind of backstory they’ve had, and if they actually were other leftover items from a household. It felt like those things for me. They ran out of their time and were just left out.

But if you don’t look at it within the context of the film, and if you just watched those shots on its own as standalone scenes, they are documentations of Potong Pasir. We made it a point to walk around, and shoot these scenes as though it was a documentary. So those items were not placed there, it wasn’t art directed. We just found them, and for me, it’s an observation of the place and space.

Hui Hsien: Can you tell us about the title, Still is Time?

Gladys: There are two reasons why I went with this title. In the middle of the film, after the Dad transforms into a table, time went into a kind of standstill. The other reason is that at the end of the film, it feels like both characters still have time. So that was what I was alluding to.

When I was reading up about Myth, you mentioned that it was a search for a sense of belonging… And I feel like in some ways, it’s similar to the character of the Dad, with those kind of internalised emotions and that outward effect. Can you say more about this search?

Hui Hsien: You’re right. You can read the images in Myth like expressions of my emotions. Making the work is one way I try to connect my internal world with the external…to find some kind of resonance in a way. But while my work is personal, I would prefer people to kind of enter it with their own experiences and emotions. So in that way, the work is really for them and not just me. And my job is just to create this mental space where people can daydream, and wrestle with that for a little while. The work is more like a gateway or tool, that they can use to reconnect back to themselves.

Puiyee: There is a spiritual element and ambiguity in your works, and I’m curious to know if art making is a sort of spiritual practice for both of you?

Gladys: Yeah,

cinema is a sort of temple where I can find a sense of peace, and learn something about myself and the lives of others. Viewing a film is quite a spiritual experience for me. Likewise, the process of art making requires you to be very focused on one task.

I often find myself watching things happen in my daily life, even when I’m not making a film. At the hospital, for example, watching how people walk and interact. I want to remember everything, in case I have to recreate these scenes some day. I find myself always looking and watching, and after a while, I lose the sense of time. So that spiritual experience is true for me.

Hui Hsien: That sounds very beautiful. I don’t think I’m a spiritual person and I think I’m just a very confused person trying to understand my place in this strange world. Making art is one way of trying to do that. But art making is a spiritual practice for me, in that it teaches me to stay in the present moment.

Like for Myth, I had to work slowly, look at everything, and think about the possibilities. I like those moments where I feel deeply connected with something, whether it is a painting, whether it is a song that makes me cry, or anything. I think those moments make me feel more human. And I feel more connected to where I am for the moment.

Gladys: I think what’s interesting in Myth, is that you work with objects that are found, which are there everyday. But yet with those very mundane objects, you’ve created this very unique force vastness of the universe. It has a sort of oneness — a one and all feeling.

Hui Hsien: I’m glad that comes across. In Myth, I am trying to suggest a sense of the spiritual or the otherworldly, because I’d like people to think a bit about the larger forces beyond their individual lives…and the vocabulary of mountains, sky and all that. These are things that have inspired cultures across the world to think about the divine, about the gods. I think the irony is that they are really made from very small, mundane bits of matter. So the question is about about perception: How much can you rely on what you see to establish what you know.

Audience Question: Gladys, before you made Still Is Time, you made The Pursuit of a Happy Human Life and My Father After Dinner. For the earlier films, there were also moments of observations of everyday life. But in Still is Time, the father turning into a table gives it this surreal fantastical element. Can you talk about the shift in your filmmaking?

Gladys: When I first wrote Still is Time, one of the very first ideas I had was that I wanted to tell a story from the point of view of an object. So from the start, there was already an element that was not realistic. At that point, I was also in a different sort of headspace…by then, I had made two films rooted in realism. I was in a mood to play. I wanted to try out different things. I wanted to play with this reality.

It was interesting when we filmed the transformation of the Dad into a table, because everyone was waiting for me to give direction. Because no one knows how a person would be like if he morphs into a table. So it was up to us to decide how that would happen, and that was pretty funny.

Audience Question: What have been some of the more interesting reactions to your work, especially since it’s important that the audience receives your works with an open mind?

Gladys: For me, it’s obviously the table. I think out of 10 people, eight or nine would come to me to ask what happened. Why did he turn into a table? I usually reply that it’s up to you to look at what happened and decide for yourself. It could be that he died, or you can take it at face value that he turned into a table and back into a human being in the end, or that he went missing. So you can read it in many different ways.

After the Dad turned into a table, I wanted the audience to ask, from whose point of view are we seeing these shots? Because we moved from an active camera movement of being in the thick of action, to a step back, as if we’re observing what’s happening. As if the Dad is observing from afar and floating around.

Puiyee: You’ve shown the film in Singapore and Sweden. Have the audiences’ reactions been different?

Gladys: Funnily enough, the Swedes were more curious about the cultural context of a wedding. For example, what the gatecrashing was about, what people were doing. They were not so concerned about the Dad turning into the table!

Hui Hsien: After looking at my work, a few people have commented about how it opens up the mind…and it’s funny because the discussions have sometimes led to different ways we can open up our minds.

Audience Question: How do you find and negotiate the solitary and collaborative aspects of your practice and process?

Gladys:

Filmmaking is a highly collaborative process, and it’s difficult to make a film alone. But for me, the writing portion usually happens alone, and I’m always lost in my thoughts. So I would definitely start by writing first. Then I start sharing ideas with people I trust, and they share theirs.

For example, when I wrote the scene where the Dad enters the house. Initially, this was written as four different scenes. If you think about the action — there was the living room area, the dining area where the bridesmaids were, and the bride in the room. When my DP Kang Wei read the script, and eventually when we went to the location, he told me that he saw everything happening at once. It felt like it had to be broken down in the script as different scenes, because that’s how you write — broken down into paragraphs. But to him, it felt like everything was happening all at once. So I said, yeah, actually maybe you’re right. And then we decided to shoot everything in one shot.

What’s helpful for me is having these honest conversations, but I also do take the time to reflect on them, because I need the time to think them through. So I guess it’s about juggling them both.

Hui Hsien: Like you,

when it comes to shooting — which is like scripting for you — it’s more or less solitary. And when it comes to sequencing images like whether it is for a slideshow or for a book, the first draft is always alone for me, because for me it’s like crafting a song or wanting to listen to the image, whether the image is soft, loud, a comma, a pause or whether it goes on to be something else. I want to be alone at that stage. But when I put it out, like in a form of an exhibition, I like to have opinions, and get feedback from others in the same space as me. So that part becomes collaborative.

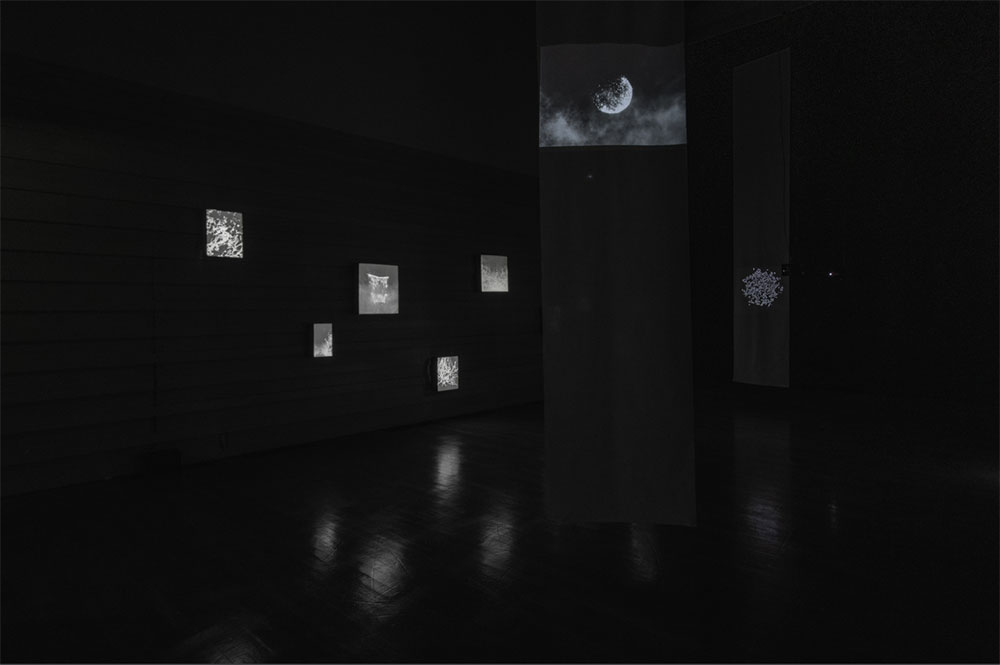

Hui Hsien’s residency show at Akiyoshidai International Artist Village, Japan, in March 2020

Audience question: I really love the sound design in your film, especially that particular moment where it sounds like everything goes mute. How do you go about thinking about sound in this film or in your other projects?

Gladys: I’m so happy someone asked about sound, because Ting Li, who was also on the last Film Club session, worked on the sound for this. How we thought about sound was mostly intuitive. When Wei Ting, the editor, and I were cutting the film, we kept feeling like something was off. We wanted the Dad to feel really distant, especially when he’s watching everything, But we couldn’t quite get that sense. So we decided to bring all the sounds down.

When we went to Ting Li, she was open to using whatever was there. And one of the first things that she told me was: actually, the film works already and I’m just going to clean up and touch up a little bit for you, but I’m not going to do overdo it. I thought it was pretty incredible for her to say it, because I think most people would try to put in a lot of things to kind of make themselves known. But I thought she took a very respectful step, which was surprising to me. And so she built a lot of the soundscape when the Dad was standing at the staircase landing, with the sounds of birds and so on.

Generally though, I don’t actually think about sound so much! I like to describe things as taste. For example, I’ll say something tastes very bland. Or sometimes I’ll watch a film, and think, it’s very over-seasoned!

Audience question: Your previous works have also touched on family and documenting parents. Was Still In Time in any way a natural continuation on exploring this topic? Was the approach and treatment, similar or different in this film compared to before?

Gladys: Still is Time came right after My Father After Dinner. So I wrote the script first, before The Pursuit of a Happy Human Life, but I made it later. So I was in the same headspace. In My Father After Dinner, the family is very nurturing. There are some melancholic moments in that, but generally very loving.

For Still Is Time, I pushed the parent child relationship a bit more. When some people watch the film, they’ll tell me that they relate to the daughter, and they feel bad. But for me, it’s not about feeling bad. It’s not meant to inspire any kind of guilt. It’s more about this sense of attachment and being unable to let go of it, and sometimes holding on too tightly isn’t that good as well. And I wanted to explore that…not in a negative sort of way, but as what it is.

Audience question: I imagine there is a lot that goes into conceptualising and researching before the actual shoot. Could you tell us about an instance in which your best laid plans did not transpire and resulted in an unexpected piece of work?

Hui Hsien: For Myth, I had experimented a lot with leaves and even with printing on leaves, and that failed terribly. I was in the UK, and it was autumn moving on to winter…and I was running out of leaves to experiment on! Then I learnt that there are certain kind of trees which shed bark. I collected those, and incorporated materials directly into the process, instead of printing on them. As I put them on the darkroom enlarger, it looked to me like a sea. So there was the image that pointed a direction for me.

Gladys: I plan most of the stuff by the time we get to production. So if anything unexpected happens, it is usually that sweet spot after I’ve written the script and before production phase, when the planning is still happening. As I mentioned earlier, like going to the location and finding new ideas, and then returning to the script, maybe changing it and new ideas kind of come as well. I would say that’s where the unexpected happens.

Audience Question: Are you keen on continuing to explore magical realism in your future films?

Gladys: For me, the process is very meandering, and I would go somewhere, get new ideas and change stuff. So most of the time I don’t really know where or how things would end up, and I do find it hard to promise some things. So the answer is yes and no, maybe not.

Audience Question: What is your casting process like? Do you have a specific idea of how your characters look when you write your script?

Gladys: The Dad auditioned twice. I wasn’t there for the first time, but watched the audition tape. He was very nervous, asking if he should sit or stand, and he was quite awkward. And I thought, he actually suits the film. So I decided to meet him in person. Everyone else was like, are you sure? But he turned out to be amazing. It all came from him. I could tell him a long story, and try to drag him, but if he wasn’t able to do it, it wouldn’t have worked. So I think even the casting process was quite intuitive… And I guess I go with my instincts.

Audience question: Who are some of your influences, filmmakers, photographers or visual artists?

Gladys: I know we both like Japanese photographer Rinko Kawauchi, for her texture and mood. I’m also a big fan of Hirokazu Koreeda.

Hui Hsien: I enjoy films by Wong Kar Wai, and I like painters like Mark Rothko, and some photographers like Rinko Kawauchi, Jeff Jacobson and Meghann Riepenhoff.

Still is Time along with with other short films by Southeast Asian filmmakers, is available to rent on the Objectifs Film Library. More titles will be able to view at Objectifs’ premises (after we reopen, depending on the Covid-19 situation).